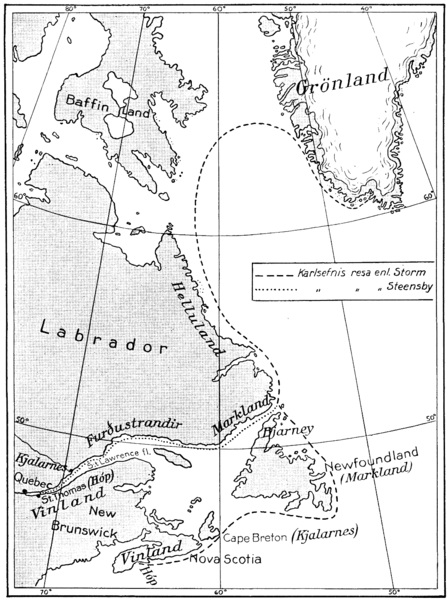

Shortly after the Norse colonization of Greenland under Erik the Red in 986, there were reports by the Viking sea kings of three new lands to the west of Greenland: Helluland (Baffin Island and the northern part of Labrador); Markland (central and southern Labrador); and Vinland (Newfoundland and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Over the past fifty years or so, archaeology has revealed over 300 years of sporadic contact between the Greenlandic Norse and various Indian, Inuit, and other Native American peoples, concentrated primarily in the Canadian Arctic.

The Sagas:

Archaeology involves much more than just digging holes to find neat stuff to put into museums. While archaeology uses material culture as a means of understanding the past, it also uses oral traditions as well. With regard to the archaeology of the Viking presence in North America, the story begins with oral traditions describing the Viking ventures into this region.

The Icelandic sagas are based on oral traditions. They are stories of events which took place in the period between 930 and 1030, an era known as söguöld (Age of the Sagas) in Icelandic history. The stories describe voyages, migrations, and feuds. The sagas focus on history, particularly genealogical and family history. These are stories from a time when Iceland was a remote, decentralized society with a rich legal tradition.

Sometime after 1190, these stories were written down in Old Norse. They existed in a pure oral form for at least two centuries. In the twentieth century some scholars, trained to trust only written history and only that history which was recorded at the time it happened, refused to look at the Sagas as history, but saw them only as literature, as fictive accounts of a mythical past. On the other hand, some archaeologists have long viewed oral traditions as important data for understanding the past. In 1960, archaeologists finally uncovered a site in Newfoundland which verified the accounts in the Sagas.

L’Anse aux Meadows:

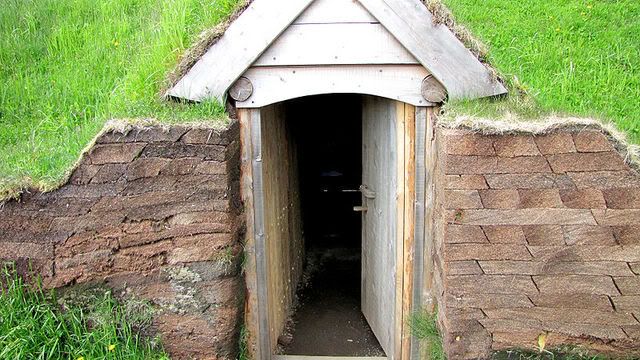

The only confirmed (that is, accepted by most archaeologists) Viking site in North America is at L’Anse aux Meadows located in Newfoundland. The site was settled about 1000 and was occupied for only about a decade. The site appears to correspond with the Leifsbuðir described in the sagas.

The archaeological remains of a hall at L’Anse aux Meadows is shown above.

The site contains eights buildings, of which seven were grouped into three complexes. Two of the complexes are composed of a large, multi-roomed hall which is flanked by a small, one-room hut. The third complex, the southernmost, has a third structure: a small, one-roomed house which is larger than the huts but smaller than the halls. The eighth building at the site is a small hut, located away from the others, on the other side of the brook and closer to the shore.

The three large halls at L’Anse aux Meadows are distinctly Icelandic with regard to the number of rooms and their placement, the type of interior walls, and the placement of roof-support posts, doors, and fireplaces. Stylistically, the large halls appear to have been built in the eleventh century.

Each of the three halls contained a workshop. In the southern hall, the workshop was a smithy where iron was forged. Iron production at the site appears to have been limited to a single smelting episode. Only a very small quantity of iron seems to have been produced and this was most likely used to make new boat nails.

The middle hall had a small carpentry shop which faced toward a sedge-peat bog. The archaeologists have found hundreds of pieces of carpentry debris outside of this shop.

Shown above are photos of a reconstructed hall at L’Anse aux Meadows.

The construction of the buildings at the site indicates that they had been built for year-round use. They do not appear to have been seasonally occupied buðir (booths).

Overall, archaeologists estimate that 70 to 90 people lived at the site: 36 to 54 in the two larger halls, about 24 in the smaller hall, and 7 to 14 in the small house and huts.

One of the interesting pieces of information from L’Anse aux Meadows comes from what was not found at the site. At Norse sites with large halls, such as those found at L’Anse aux Meadows, there are usually a number of outbuildings for the animals. While the Vikings are often portrayed in the popular media as warriors, they were actually farmers for whom their cows, sheep, and goats were important to their subsistence. At L’Anse aux Meadows, archaeologists did not find any byres, animal pens, or corrals. If they had domestic animals with them, they must have been left out in the open, or perhaps slaughtered before stabling was required.

The lack of evidence regarding animals suggests that, unlike the Viking efforts in Greenland, this was not a colonizing effort. While the site was occupied year-round, it was not intended to be a self-sustaining colony which depended on farming for its livelihood.

L’Anse aux Meadows was a location from which the Vikings launched parties to explore areas farther away. It appears to have been a base which may have housed three ship crews. Archaeologists have found unequivocal evidence that they went south to warmer, more hospitable areas where butternuts grew on large trees and grapes grew wild.

Butternut trees, a type of North American walnut also known as white walnut, are not indigenous to Newfoundland. The area closest to Newfoundland in which butternuts are found is the Saint Lawrence River Valley. At L’Anse aux Meadows, archaeologists found butternuts and a large butternut burl which had been cut with a metal tool. Since butternuts grow in the same area as wild grapes, whoever picked the nuts and brought the wood back to L’Anse aux Meadows must have come across grapevines as well. Once again archaeology provides proof that the Saga stories of the Norse encountering wild grapes is not a myth, but was based on reality.

A reconstruction of a small Viking boat at L’Anse aux Meadows is shown above.

Contact With Indians:

The archaeological records do not reveal very much about the interactions between the Vikings and Native Americans. However, there are a number of stories in the Sagas about contact with the Natives whom they called Skraelings, a derogatory term which was used to describe a number of different people. The Native Americans who confronted the Vikings were very different than anyone they had ever encountered. The Indian people who dealt with the Vikings were probably Algonquian-speaking, most likely the ancestors of the Montagnais, Naskapi, and Beothuk.

According to one story, Leif and the other Viking warriors fled their village and cowered behind some rocks when the Skraelings attacked. Freydis Eriksdottir, then nearly nine-months pregnant, tore open her blouse to expose her breasts, then picked up a shield and sword dropped by the fleeing Vikings, and counter-attacked. She succeeded in repelling the attack and defending the brave Viking warriors.

In another story, Karlsefni and his people had sailed to the mouth of the river in an area which they called Hop. According to the Sagas:

And early one morning, as they looked around, they beheld nine canoes made of hides, and snout-like staves were being brandished from the boats, and they made a noise like flails, and twisted round in the direction of the sun’s motion.

Then Karlsefni said, “What will this betoken?” Snorri answered him, “It may be that it is a token of peace; let us take a white shield and go to meet them.” And so they did. Then did they in the canoes row forwards, and showed surprise at them, and came to land. They were short men, ill-looking, with their hair in disorderly fashion on their heads; they were large-eyed, and had broad cheeks. And they stayed there awhile in astonishment. Afterwards they rowed away to the south, off the headland.

Another story in the Sagas describes trade with the Skraelings:

Now when spring began, they beheld one morning early, that a fleet of hide-canoes was rowing from the south off the headland; so many were they as if the sea were strewn with pieces of charcoal, and there was also the brandishing of staves as before from each boat. Then they held shields up, and a market was formed between them; and this people in their purchases preferred red cloth; in exchange they had furs to give, and skins quite grey. They wished also to buy swords and lances, but Karlsefni and Snorri forbad it. They offered for the cloth dark hides, and took in exchange a span long of cloth, and bound it round their heads; and so matters went on for a while.

Stories of encounters with Native Americans who had superior numbers and could hold their own in a fight with the Vikings discouraged permanent Norse settlements in North America.

Other Sites:

A re-enactment of the Viking landing in North America is shown above.

While L’Anse aux Meadows is the only Viking archaeological site known in North America at this time, the Sagas certainly describe many other possible sites. According to the Sagas, the Vikings and their cattle settled at several of these sites and remained in them at least through the winter.

With regard to the land called Hop in the Sagas:

Karlsefni proceeded southwards along the land, with Snorri and Bjarni and the rest of the company. They journeyed a long while, and until they arrived at a river, which came down from the land and fell into a lake, and so on to the sea. There were large islands off the mouth of the river, and they could not come into the river except at high flood-tide.

With regard to their settlement at Hop, the Sagas say:

They had built their settlements up above the lake. And some of the dwellings were well within the land, but some were near the lake. Now they remained there that winter. They had no snow whatever, and all their cattle went out to graze without keepers.

A map of the Viking world is shown above.

While the last recorded voyage to North America was made by Thorfinn Karlesfni, who was married to Gudrid (the widow of Leif’s brother Thorstein), about 1015, there were numerous hunting and trading expeditions into the area between 1050 and 1350. Some of these expeditions travelled into Hudson’s Bay. The need for timber often motivated the Greenland Norse to make the voyage to Markland. In 1347, one ship drifted off course after having made a trip to Markland and eventually reached Iceland.

I love reading about my ancestors. I have read a number of books, the most readable of the lot is Robert Ferguson’s “The Vikings: A History”. Loved the book. He spends a scant few pages on LAnse aux Meadows,saying that it is (or was) Vinland of the Sagas. A quick Wiki search says that Leifsbuðir was part of Vinland (Robertson never mentions Leifsbuðir, though).

Thanks, Ojibwa! As always, your essays are very interesting.