The text of this post was a collaborative project of navajo and Meteor Blades. All but four of the photos, most of which appear below the squiggle, were taken by navajo.

|

This is the third in a year-long series being posted at Native American Netroots dedicated to revealing how American Indians – on reservations and in urban environments – are mostly invisible, a product of long-standing U.S. policy and societal ignorance.

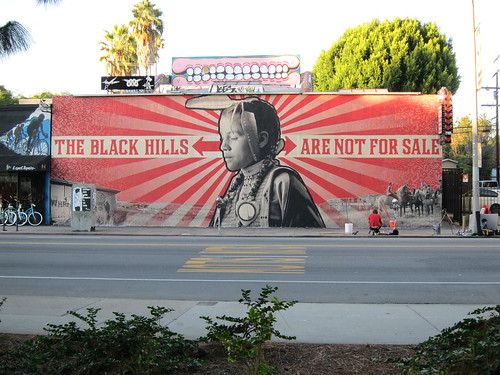

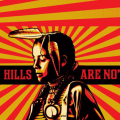

On Nov. 26, 2011, Harper’s magazine Contributing Editor and National Geographic photographer Aaron Huey joined Shepard Fairey, the prolific street artist known to most people for his iconic Obama HOPE campaign image, and installed a stunning 20×80-foot mural THE BLACK HILLS ARE NOT FOR SALE. It’s at the intersection of Ogden and the highly trafficked Melrose Avenue in West Los Angeles near Fairfax.

The result is a beautiful, intriguing “billboard” that we hope will spur those who walk and drive by to educate themselves about what it means. The composition brings visibility to a group that is otherwise pretty much hidden from the rest of the nation, the Lakota people of South Dakota.

|

|

| HISTORY AND BACKGROUND: |

|

The Black Hills (He Sapa in Lakota, the language of the people most Americans know as Sioux) were wrenched from the tribes in 1877. Starting in 1922, the Lakota have sought what has become an 89-year-long array of complex legal efforts to have them returned, so far without success.

In 1950, the Sioux Nation filed a petition with the Indian Claims Commission for He Sapa and other lands based on two factors: treaty violations and lack of compensation. Thirty years later, ruling in what is one of the longest running court cases in U.S. history, United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, the Supreme Court ruled that the Lakotas had been unjustly moved onto reservations and 7 million acres of their lands, including the He Sapa, illegally opened up to prospectors and homesteaders in violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Rather than give the Black Hills back, the court affirmed a lower court decision backing the ICC’s award of $106 million in compensation, which included 103 years of compound interest. It did not include compensation for the vast amount of minerals that have been extracted from the area.

The Sioux Tribal Council said no to the settlement, fearing that agreeing to take the money would mean they could never get back the sacred He Sapa. Thus the slogan, “The Black Hills are not for sale.” In the 30 years since then, the compensation fund held by the government has grown to more than $1 billion, and the pressure inside the Sioux Nation to accept payment has grown in great part because of the continuing poverty and associated ills the Lakota people endure decade after decade. This past August, a case brought by 19 Lakotas seeking to have the money divided equally among individuals was dismissed by a federal court to the relief of tribal leaders.

Considerable hope has been placed in President Obama to resolve the issue. Unlike past presidents, he is widely viewed among Indians to have actually listened to our concerns and promised to deal with them fairly. Since the highest court has made its ruling, only the President and Congress can change things.

Some solutions have been suggested with varying degrees of acceptance among Lakotas. One proposal would release the accumulated funds from the court-ordered settlement and turn over the federally owned land in the Black Hills and other nearby lands. Excepted would be Mt. Rushmore, which hosts the granite faces of four presidents who presided over the taking of Indian land from coast to coast. No private land owned by non-Lakotas would be part of the deal.

In 2009 the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association formed the Great Sioux Nation He Sapa Reparation Alliance in hopes of presenting a unified voice for realizing a settlement that would hold the United States responsible for the violations of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty and take action on both the land and compensation issues. Nearly 135 years after the Black Hills were taken, the Lakota people still want them back and seem determined not to sell them, not even for a billion dollars.

Here’s a video of Aaron Huey’s TED talk on the Lakota people and the broken treaties:

Transcript of Aaron’s talk and a timeline of treaties made, treaties broken and massacres disguised as battles.

Excerpt:

I have been asked to talk about my relationship with the Lakota. That is a very difficult thing for me because, if you haven’t noticed from my skin color, I’m white. And that will always be a huge barrier on a native reservation. You will see a lot of people in my photographs today. I’ve become very close with them. They have welcomed me like family. They called me “uncle: and “brother” and they welcomed me back many times over in my five years of visits. But on Pine Ridge I will always be what is called Wasi’chu. Wasi’chu is a Lakota word that means “non-Indian,” but another version of this word means “Takes the best part of the meat.” And that is what I want to focus on today: “The one who takes the best part of the meat.” It means “greedy.”

Aaron has been photographing his friends on Pine Ridge since 2004. His goal now is to bring much-needed attention to the Lakota and the history of broken treaties with the U.S. government at Honor The Treaties.org

Ojibwa has more history on American Lies and the Treaty of Fort Laramie

|

| THE INSTALLATION: |

|

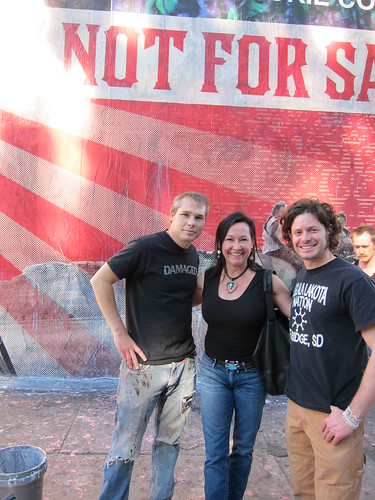

Meet Miguel Garcia, in the center, with Shepard Fairey on the left and Aaron Huey on the right, Miguel is owner of De La Barracuda, a boxing club at 7769 Melrose. Miguel donated the wall for this installation. The prominent space normally rents for $15,000-20,000.

We arrive after an 85 mph trip from San Francisco at midday and the work is well under way. They started at 11 a.m. This is Shep walking briskly along the wall, directing the volunteer installers.

Volunteers have pasted all that can be done at ground level and are now boarding the scissors truck to reach higher spots.

They have gone through many buckets of wheat paste by the time we arrive.

Shep scoops up excess wheat paste.

Shep swabs the installed paper pieces with a thick coat of wheat paste.

Daryl Hannah and Aaron, who met her at the MountainFilm Festival in Telluride, Colorado this past May. She is now an avid supporter of his Honor the Treaties: Pine Ridge Billboard Project.

Daryl cuts paper snippets of the image to correct imperfections in the pasting. She was on site for several hours.

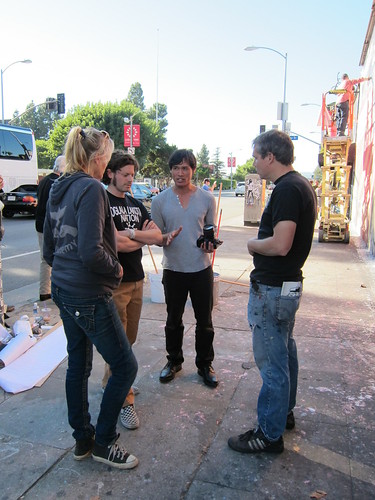

Aaron plots logistics with Shep.

Daryl and Chet Hay (Aaron’s assistant) join Aaron and Shep to discuss some details of the installation.

Chet keeps the mural pieces organized.

Lakota pow-wow dancer’s ear is hoisted for installation.

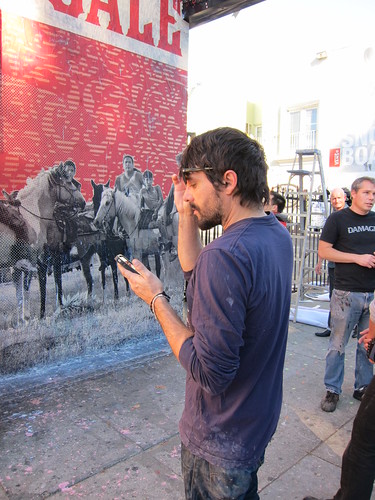

This is Sinuhé Xavier. He knows Miguel, the club owner, and after he met Aaron, he connected the two.

A large portion of the beautiful Lakota pow-wow dancer’s face is being installed by Shep and other members of the team.

Aaron stacks paper strips for the next upload.

Shots taken by co-author Meteor Blades:

This figure with the outstretched arms is co-author navajo showing how extremely happy she is to be there.

Shep, Aaron, Meteor Blades, Shockwave and Lara. Honorary SFKossacks Represent!

Shep, navajo and Aaron.

Shep’s presence being documented.

Watching and waiting for the next hand-off of paper.

Daniel Salin, a producer and curator for art shows and an installer for the famous international street artist Banksy, takes a break from working on the scissors truck. Daniel was connected with Aaron through Sinuhé. He has done the Barracuda wall before with Shep and photograffeur JR.

Documenting is done from all angles.

Daniel, Shep and Eric Becker

The face gets closer to completion.

Urban Indians: navajo and her daughter mangolind watch the mural’s progress.

Aaron and Shep paste the mural’s strips on the top edge of the wall.

Shep and Daniel, covered in wheat paste.

Aaron finishes the last square of paper!

He turns around with a grin.

Aaron, Daryl and Shep pose with the completed project.

Now for the Pièce de Résistance: The billboard is tagged with HONOR THE TREATIES.org

Chet, Aaron, Sinuhé and Daniel are happy to be done.

Sinuhé and Aaron snap pics of their work from across the street.

Aaron, navajo, Sinuhé, Daniel and Taylor Kent, who documented the project with a time-lapse camera across the street.

You can browse more than 290 of navajo’s photos of the installation here by clicking the slideshow button.

|

| HOW YOU CAN DIRECTLY HELP THE LAKOTA: |

|

#1: Share and Tweet this diary with your networks.

Honor The Treaties at Facebook.

#2: Support the organization that directly helps the youth of Pine Ridge who are featured in the images above.

The Owe Aku International Justice Project DONATE is guided daily by traditional leaders and elders who speak our language and live our Lakota way of life. This approach has preserved our nation for 170 years against unyielding attempts to annihilate, assimilate and legislate us out of existence. Our goal is to do nothing more than continue the process left to us by our ancestors.

Thanks so much for putting this together. It really got us close to the installation. I hope this becomes a mural movement that springs up around the country, as Aaron is hoping.