Welcome to the seventh edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the “Invisible Indians” project put together by navajo and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Last week’s edition is here. In this edition you will find a remembrance by Carter Camp of the Wounded Knee siege 39 years ago, a look at the year 1954 in American Indian history, five news briefs and some linkable bulleted briefs. Click on any of the headlines below to take you directly to that section of News & Views or to any of our earlier editions.

This Week in American Indian History in 1954

First Totem Pole in a Century Raised in Seattle for Victim of Police Shooting ~ Two Vermont Abenaki Bands Expect State Recognition ~ Navajo Nation Sues Urban Outfitters Over Use of Tribal Trademark ~ “Fighting Sioux” Fight in North Dakota Gets Hotter Still

Still Matters Today

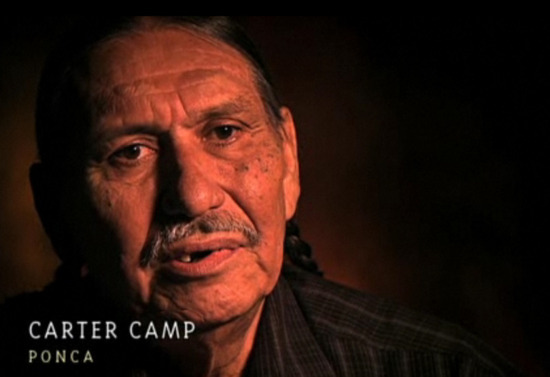

Carter Camp marked as a warrior at Wounded Knee, S.D., in the late winter of 1973

Thirty-nine years ago at the end of February in 1973, some 250 Oglalas and their supporters in the American Indian Movement took over the hamlet of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in southwestern South Dakota. The immediate catalyst for the protest was the corrupt leadership of the tribal chairman, Dick Wilson. By many traditional Oglala, he and his administration were viewed as an extension of the “colonial” system that had ruled the reservations for decades despite a veneer of sovereignty conveyed by the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

But their objections in this specific matter had their roots in a different, broader issue, one that remains unresolved to this day, the unfulfilled promises in hundreds of broken treaties and other agreements between Indians and the U.S. government. Those pacts smoothed the way across the nation for the expropriation and occupation of the land of hundreds of tribes as well as the destruction of our culture, our languages, our religions and our traditions.

By the time of Wounded Knee, AIM had been in the forefront of high-profile protests against the injustices against Indians by the government for nearly five years. It had already organized an occupation of Alcatraz Island, marched across the country to Washington in the Trail of Broken Treaties, and occupied BIA headquarters, making off with boxes full of documents after a week inside the building.

The takeover at Wounded Knee had resulted in a siege by U.S. Marshalls and the FBI that lasted 73 days. I was there for 51 of those days, leaving only when it briefly appeared a resolution had been achieved. The siege continued for another three weeks. When it was over, two members of AIM and one federal marshall were dead. In the following two years, 60 AIM members and two FBI agents were also killed.

Though his name is less known than that of Russell Means and Dennis Banks, in the AIM leadership at the time was a young Ponca man named Carter Camp. He was chosen as war chief.

But let my friend Carter tell this story in his own words, compiled from a number of his writings and interviews over the past dozen years.

-Meteor Blades

By Carter Camp

Carter posts at Daily Kos as cacamp.

Ah-ho, My Relations,

I ask you to remember that our reasons for going to Wounded Knee still exist and that means the need for struggle and resistance also still exist. Our land and sacred sites are threatened as never before. Even our sacred Mother herself is faced with unnatural warming caused by extreme greed.

White House’s response to the siege and asked for

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to visit.

Here an interviewer asks Carter Camp if that’s really

necessary. Camp asks, “Why not? Indians are just as

important as any other issue the U.S. has, like Vietnam.”

In some areas of conflict between our people and those we signed treaties with, it is best to negotiate or “work within the system.” But, because our struggle is one of survival, there are also times when a warrior must stand fast even at the risk of one’s life. I believed that in 1973 when I was 30 and I believe it today at 70. But to me Wounded Knee ’73 was really not about the fight, it was about the strong statement that our traditional way of living in this world is not about to disappear and our people are not a “vanishing race” as wasicu (white) education would have you believe. As time has passed and I see so many of our young people taking part in a traditional way of living and believing, I know our fight was worth it and those we lost for our movement died worthy deaths. […]

Today is heavy with prayer and reminiscence for me. Not only are those who walk for the Yellowstone Buffalo reaching their destination, today is the anniversary of the night when, at the direction of the Oglala Chiefs, I went with a special squad of warriors to liberate Wounded Knee in advance of the main AIM caravan.

For security reasons the people had been told everyone was going to a meeting/wacipi in Porcupine, the road goes through Wounded Knee. When the People arrived at the Trading Post we had already set up a perimeter, taken 11 hostages, run the BIA cops out of town, cut most phone lines, and begun 73 days of the best, most free time of my life. The honor of being chosen to go first still lives strong in my heart.

That night we had no idea what fate awaited us. It was a cold night with not much moonlight, I clearly remember the nervous anticipation I felt as we drove the back way from Oglala into Wounded Knee. The Chiefs had tasked me with a mission and we were sworn to succeed, of that I was sure, but I couldn’t help wondering if we were prepared. The FBI, BIA and marshalls had fortified Pine Ridge with machine-gun bunkers and armored personnel carriers with M-60s. They had unleashed the GOON squad [Dick Wilson’s Guardians of the Oglala Nation] on the people and a reign of terror had begun. We knew we had to fight, but we could not fight on wasicu terms. We were lightly armed and dependent on the weapons and ammo inside the Wounded Knee trading post, I worried that we would not get to them before the shooting started.

As we stared silently into the darkness driving into the hamlet, I tried to foresee what opposition we would encounter and how to neutralize it. We were approaching a sacred place and each of us knew it. We could feel it deep inside. As a warrior leading warriors I humbly prayed to Wakonda for the lives of all and the wisdom to do things right. Never before or since have I offered my tobacco with such a plea or put on my feathers with such purpose. It was the birth of the Independent Oglala Nation.

Things went well for us that night, we accomplished our task without loss of life. Then, in the cold darkness as we waited for Dennis and Russ to bring in the caravan (or for the fight to start), I stood on the bank of the shallow ravine where our people had been murdered by the 7th Cavalry [in 1890]. There I prayed for the defenseless ones, torn apart by Hotchkiss cannons and trampled under hooves of steel by drunken wasicu. I could feel the touch of their spirits as I eased quietly into the gully and stood silently, waiting for my future, touching my past.

Finally, I bent over and picked a sprig of sage – whose ancestors in 1890 had been nourished by the blood of Red babies, ripped from their mothers’ dying grasp and bayoneted by the evil ones. As I washed myself with that sacred herb, I became cold in my determination and cleansed of fear. I looked for Big Foot and YellowBird in the darkness and I said aloud:

“We are back, my relations, we are home.”

2009 PBS special, “We Shall Remain.”

We were fighting every day and in danger every day. But it was a lot of fun. During the lulls in the fighting, or during the time when there was not actual danger, it was just a wonderful time being together. People would break out the drum every night and we’d sing together, and different tribes would sing their songs. We had Indian ceremonies that are very special to us, but we don’t bring ’em out in public. But now we could have ’em right there where everybody could participate. We don’t have to hide them around anymore. We had the elders, medicine men, women and children – all in Wounded Knee with us.

We were a strong community. We all had work to do and fighting to do. But at the same time, we could live together and do the things that we wanted to do, say the things that we wanted to say and understand this world the way that Indian people understand it. So it made us feel good. We just really were able to come together in a unity that you don’t hardly find in Indian Country. We’re different tribes and we don’t always get around to each other like that. I mean literally thousands of Indian people were coming from around the country. At any one time we might only have 700 or 800 people in Wounded Knee, but people were coming and leaving. Then, of course, a group of AIM people and the traditionalists stayed there throughout the thing.

Wounded Knee galvanized Indian Country, all over. During those 73 days we were in there, from Seattle to Washington, D.C., and from New York to Florida, Indian people were trashing BIA offices, protesting at the Indian Health Services, telling their own tribal governments to stop the leases with the uranium companies and the coal digging and that sort of thing. Indian people were just making themselves known.

Wounded Knee and the rise of the American Indian Movement and the struggle of the late ’60s and ’70s just changed everything about the way Indian people think of themselves. They started thinking in terms of the future, not of being exterminated or maybe this is our last generation that cares about being Indian. It just invigorated the entire Indian nations […] They started having pride in where they came from and what they were and who they were. […] It also made the government understand that once more there was a line in the sand that they couldn’t push us beyond. We had taken all we could absorb and that if they pushed us just too damn far then we’ll fight.

There is a excellent PBS documentary about the Wounded Knee takeover and siege on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Carter is featured in this 80-minute segment, We Shall Remain, Wounded Knee, Episode 5. (h/t exmearden)

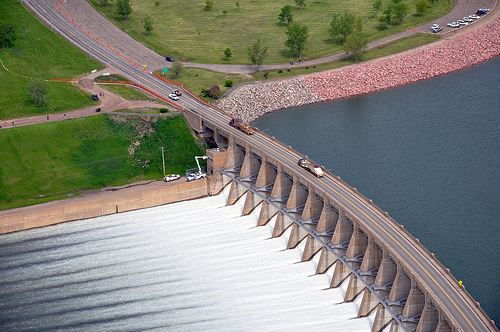

On Feb. 27, 1954, the U.S. government took additional land from the Yankton Sioux Tribe to build the Fort Randall Dam and Reservoir in southeastern South Dakota. That dam and four others built on the Missouri River by the Army Corps of Engineers from 1946 to 1966 were approved for flood control, pollution and sediment control, navigation, conservation, recreation, hydroelectric power and enhancement of fish and wildlife under the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program, a part of the Flood Control Act of 1944.

Construction of the dams and consequent flooding forced the relocation of more than 1500 Indian families on seven reservations, including some 136 on the Yankton Reservation. The tribes lost more than 350,000 acres. Besides the Yankton Reservation, fertile bottom land was condemned on reservations at Fort Berthold, Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, Lower Brule, Crow Creek and Santee.

The tribes didn’t only lose their land but also any timber, wildlife and native plants plus homes and ranches. In the case of Fort Thompson on the Crow Creek Reservation, an entire town was inundated. As a consequence, the BIA and Indian Health Service offices were moved off the reservation to Pierre, making it far more difficult for Indians they were supposed to serve to use them.

The losses also included spiritual ties to the land and the intangible benefits that came from living along the Missouri.

The tribes were never consulted about the project during the planning stages. No Indians were asked to testify during hearings on the projects in Congress. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, which supervises Indian land held in trust by the Department of Interior, raised no objections.

The Corps of Engineers handled negotiations. Tribal sovereignty and treaty rights, including the Yankton Treaty of 1858, were completely ignored. So also was the Winters Doctrine, a Supreme Court ruling that Indians have inherent rights to water resources on their lands. Philleo Nash, who had advised Presidents Roosevelt and Truman to integrate the Armed Forces and later served as BIA Commissioner under JFK and LBJ, would later say that Pick-Sloan “caused more damage to Indian land than any other public works project in America.”

The amount of money offered to owners of individual Indian land allotments was often significantly less than the amount offered to non-Indian land owners. Likewise, as the dam projects began in a time when termination of reservations was in full swing, government compensation for damages caused by the taking of communally owned tribal land was well below its market value. Land at North Dakota’s Fort Berthold Reservation of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara people was condemned and bought for $33 an acre. Today, the earthen Garrison Dam is on the land, holding back Lake Sakakawea, and capable of generating some 583 megawatts of electricity.

Twenty-five years after the last dam was completed, the General Accounting Office undertook the first of four reports on providing better compensation, which you can see here: 1991; 1998; 2006; and, 2007

Today, the tribes whose land was taken have an on-reservation population of about 32,000, with another 20,000 enrolled members living elsewhere.

-Meteor Blades with a h/t to ojibwa

First Totem Pole in a Century Raised in Seattle for Victim of Police Shooting

folk hero John T. Williams

is at 11th Avenue

between Pike and Pine

The strength of a First Nations community came together on Feb. 26 when a 33-foot-tall, 5,000-pound totem pole was ceremoniously carried a mile-and-a-half from its carving site on the shoulders of scores of supporters and erected near the 50-year-old Space Needle. It was the first totem pole erected in Seattle in nearly 100 years. Conceived and carved in the traditional manner, the cedar totem pole honors John T. Williams (Ditidaht), himself a master carver, who was shot and killed by Seattle police officer Ian Birk in August 2010. After months of protest by Indians and their supporters, the shooting death was found not justified. Officials said Birk took actions that were “outside of policy, tactics and training.”

As can be seen and heard in this disturbing video here, Birk stepped from his patrol cruiser and came up behind Williams on the street, who was walking and carrying a small, legal folding knife and a plank of wood which he had been carving. Birk told Williams to put down the knife. He then shot Williams four times in the back, killing him instantly. The entire encounter took eight seconds. Facing termination from the force after the damning report was released, Birk resigned.

Immediately after the shooting, the Williams family reported strained relations with police. They said they were being scrutinized and harassed by bicycle patrol officers in a street market where vendors have sold their goods for decades. Other Native people complained in public forums that they had good reason to feel unsafe around the police. Demonstrations erupted and community meetings turned into shouting matches.

Over time, the tensions relaxed. One element that helped bend police officials and Native peoples toward better interaction was the initiation of a restorative circle, a practice developed in Brazil by Dominic Barter.

In December 2011, the U.S. Department of Justice released the findings of its investigation of the City of Seattle Police Department. It concluded the SPD has a “pattern and practice” of using excessive force, especially in communities of color, and that it needs structural reform in training, supervision and discipline. While disagreeing with aspects of the report, the department has stated it will overhaul its use of force policies and procedures.

The Williams family’s seven generations of traditional carving inspired Williams’s brother Rick to design a totem pole that turned the tragedy into an honoring of his brother’s life and heritage. Rick called for a peaceful resolution to the community conflict that followed the fatal shooting but had been building beforehand. “Despite his grief and anger, Rick Williams, by his own account, found strength in the wisdom of his ancestors and rejected calls for violence and retribution against the police. He requested that the response to the shooting be peaceful, in respect for his brother. By his example and explicit requests, he helped keep the peace in the streets where many felt despair, outrage, the need for change, and an urge for revenge.”

The team of master carvers took more than six months to finish the totem pole. The cedar tree came from Harstine Island and was donated by the Manke Lumber Company. The loggers who cut it estimate its age to be at least 120 years. Two other totem poles carved from the same tree are in the works and will be placed elsewhere in Seattle.

The family of John T. Williams has forgiven the Seattle police force. Now at peace, they honor Williams’s life with an exquisite piece of art but also an important symbol of cultural legacy, hope and community healing.

An interpretive display at the carving site explains the figures on the memorial totem pole:

• Top: Eagle. “The Eagle flies the highest and sees the farthest, so he takes the perch at the top of the pole.”

• Middle: Master Carver. “This is a Williams family symbol handed down through seven generations of woodcarvers. This master carver is John T. Williams displaying his own signature totem, which features the Kingfisher and the Salmon. This carving, at the age of 15, made John a master carver in the Ditidaht First Nation, in British Columbia.” According to the interpretive display, John T. Williams’s works, and other Williams family pieces, are displayed all over Seattle, at the White House and in the Smithsonian. At this writing, early John T. Williams carvings are being sold on eBay for $8,500.

• Bottom: Raven Mother and Baby. “The Raven watches and nurtures us, making up the foundation of the totem.”

There is an amazing video of the whole procession and traditional raising of the memorial totem pole. http://blog.seattlepi.com/theb…

The final stage of this publicly funded project is a seating area for contemplation encircling the pole with customizable granite tiles. Interested people can make a donation at The John T. Williams Totem Pole Project to secure a tile.

You can also support the project at Facebook. Almost 3000 others have.

-navajo & Meteor Blades

Two Vermont Abenaki Bands Expect State Recognition

Under a new Vermont law, two bands of Abenaki Indians gained state recognition in 2011. Two more may now be on the verge of doing so. The Abenaki were once part of the Confederacy of the Wabanaki, the “People of the Dawn Land” in their Algonquin tongue. They ranged from modern-day New England into Quebec and the Maritime Provinces. Today bands with and without reservations live in Quebec, New Brunswick, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont.

American Affairs Luke Willard

Twenty-three states have laws that set parameters for recognition, which can confer various benefits to members that are not otherwise available. In a few cases, such as Florida, no tribe can receive state recognition unless it is already one of the 566 federally recognized tribes of Indians or Alaskan Natives. Others require some genealogical proof of native ancestry and a historical connection to the area in which they now live. A few don’t require that, and some tribally enrolled Indians consider recognition of tribes in those states to be fraudulent.

Indeed, critics have claimed that all the Vermont bands are modern inventions and that most or all of the people claiming tribal connection have no true claims to being Abenaki or Indians at all. At his web site – The Reinvention of the Alleged Vermont and New Hampshire Abenakis – Doug Buchholz has published birth certificates that he says prove some of the leading members of the tribes are fraudulent wannabes. That’s not how the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs see things.

The commission was established by the new law and recommends which tribes should be granted recognition based on nine criteria. Most of members of a tribe must live within a specific area inside the state and a large number must be related through kinship. They must have a connection to the state that can documented by historical, ethnographic or archaeological evidence. After a tribe submits its evidence, a panel of scholars and other experts reviews it and reports to the commission, which decides whether or not to recommend recognition. The legislature can grant or reject recognition then and there. Or it can choose to do nothing. If it takes the latter course, a recommended tribe gains recognition automatically after two years.

Based on these criteria, the Elnu Abenaki in Windham County and the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation in northeastern Vermont – gained state recognition last year. The two other bands of Abenaki in Vermont – the St. Francis-Sokoki Band of the Abenaki Nation at Missisquoi in northwestern Vermont and the Koasek Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation from the Connecticut River Valley – presented their evidence before a joint legislative committee hearing Feb. 14:

St. Francis-Sokoki band Chief John Churchill testified that state recognition will bring cultural pride to his band.

“Pride is a big thing. Whatever nationality one says you are, you don’t have to prove it. If you say you’re Abenaki or Native American, for some reason you have to prove it,” he said.

Roger Longtoe Sheehan, chief of Elnu Abenaki, testified on the positive cultural impact of recognition, particularly in his band’s relationship with other nations.

“It’s a pride thing so you can walk into a pow-wow and go to any sort of site that would be tied to the culture and be able to say, ‘We’re Abenaki,’” Sheehan said, later adding. “Unless you get state recognition, they basically won’t talk to you.”

State recognition can lead to some limited federal benefits, particularly in education and in grants for economic development and cultural rejuvenation. State-recognized tribes can also legally sell handicrafts such as baskets with “Indian-made” labels attached. But state recognition does not set up a government-to-government relationship of sovereignty the way federal recognition does.

Luke Willard, chairman of the state Native American Affairs Commissiion and a tribal trustee and treasurer of the Nulhegan Band has pointed out that what Vermont provides is more of a “cultural recognition.” No tax money is expended. There will be land claims, no casinos, no treaty rights fights, no battles over tax-exempt cigarette sales and or reservation tax exemptions because there is no communally owned tribal land from which to assert such claims.

Among the difficulties the St. Francis-Sokoki and Koasek have had is finding Colonial-era documents proving that a majority of members have continuously resided in the same historical area. According Erin Hale at VTDIGGER.org, Peter Thomas, the retired director of the University of Vermont’s archaeology program, thinks it doesn’t make sense to make a recognition determination based on today’s borders to a region occupied by Native people for at least 11,000 years and the Abenaki since before Anglo-Americans arrived on the Continent.

The Koasek Band ultimately was able to show that 58 percent of its members lived within Vermont’s borders. The St. Francis-Sokoki were helped by the 1973 discovery of a burial site dating back at least two millennia and another discovered in 2000 that contained the remains of 27 Abenaki, with artifacts from the 17th through 19th centuries.

Other issues include proving kinship ties because Indians and mixed-race people were often listed in the 1700s and 1800s as “pagan” or “colored,” not “Indian.” Hale writes that “Vermont’s eugenics movement in the 1920s and 1930s further damaged record keeping.”

Federal recognition was denied the St. Francis-Sokoki in the 1990s, and that was an issue for some committee members at the February hearing. But an expert witness explained that obtaining federal recognition is an expensive process requiring between $5 million and $12 million “to get the political clout in Washington to be able to get recognition.”

Willard said one of his reasons for joining the commission was to “nullify federal recognition. Why do we need federal recognition if we have a state government that is willing to work with the tribes and is willing to enact state policy and legislation that will successfully meet the needs and empower the native people of the state? I just don’t see the sense in spending millions of dollars just so you can get a thumbs-up from people who are hundreds and hundreds of miles away.”

-Meteor Blades

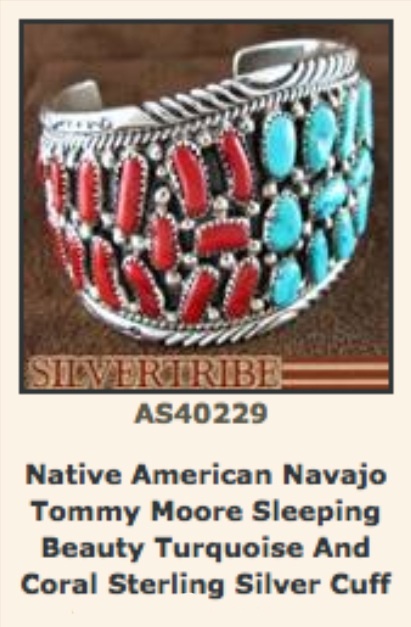

Navajo Nation Sues Urban Outfitters Over Use of Tribal Trademark

this one, are legally sold under the

Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

Months after the Navajo Nation had sent a cease-and-desist order to Urban Outfitters to stop selling their line of clothing using the designation term Navajo in the style’s name, the Navajo Nation has sued the company and its subsidiaries. The suit alleges they have violated the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 (IACA) and for trademark infringement. The Navajo Nation has 12 trademarks registered under the label Navajo. The suit was filed in New Mexico where part of the Navajo Nation reservation is and where Urban Outfitters has a number of stores.

The truth-in-advertising IACA “prohibits misrepresentation in marketing of Indian arts and crafts products within the United States. It is illegal to offer or display for sale, or sell any art or craft product in a manner that falsely suggests it is Indian produced, an Indian product, or the product of a particular Indian or Indian Tribe or Indian arts and crafts organization, resident within the United States.”

Urban Outfitters’ Fall 2011 collection had many style names that included the term Navajo. Two of the most offensive were a Navajo flask and Navajo Hipster Panties, which can been seen (if you must) at the Native Appropriations blog. Urban Outfitters was widely criticized for its stupidity in following their fashion directors’ prompts of what the latest trend is. Having once been a buyer in the fashion business, I can just imagine the boardroom excitement of naming the season’s trend, “OMG … Navajo is so hot right now!”

American designers, like sports team owners, love to “pay tribute” to this unique American icon, the “noble Indian.” But it’s not a tribute. It’s a rip-off and an insult.

Ralph Lauren, Pendleton, Dolce & Gabbana and others have been producing American Indian-themed clothing for decades with little public outcry. But now, with the power of the Internet, young Native bloggers are turning the spotlight on this long line of expropriations of land, resources, spiritualism and whatever else can be grabbed from Indians and twisted to benefit greed.

It was Sasha Houston Brown, 24, (Dakota/Santee Sioux), an academic advisor at Minneapolis Community and Technical College where she works with the American Indian Success Program, who sent a letter on Columbus Day last year to Urban Outfitters’ CEO Glen T. Senk after she visited one of their stores in Minneapolis.

…she was offended by “plastic dreamcatchers wrapped in pleather hung next to an indistinguishable mass of artificial feather jewelry and hyper sexualized clothing featuring an abundance of suede, fringe and inauthentic tribal patterns.”

Brown told […] Senk that the collection was “cheap, vulgar and culturally offensive.”

Another Indian blogger, Adrienne K. at Native Appropriations, wrote:

First of all, these products represent a stereotype of “southwest” Native cultures. The designs are loosely based on Navajo rug designs […] or Pendleton designs, but aren’t representations that are chosen by the tribe or truly representative of Navajo culture. Associating a sovereign Nation of hundreds of thousands of people wit[h] a flask or women’s underwear isn’t exactly honoring.

Additionally, it’s more than likely that Urban [Outfitters] chose “Navajo” for the international recognition–to most of the world Navajo (and Cherokee)= American Indian […] This conflation of Navajo with “generic Indian” contributes to the further erasure of the distinct tribes and cultures in the US and solidifies the idea that there is only one “Native” culture, represented by plains feathers and southwest designs.

Urban Outfitters immediately removed the Navajo designation from its site last fall. You would think the board members had learned their lesson.

Apparently not.

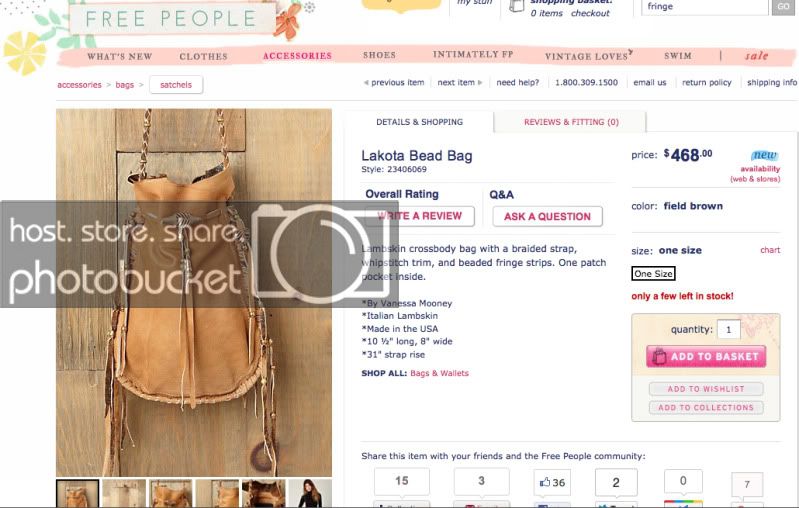

One of the company’s upscale subsidiaries, Free People, recently ran a distinct collection of styles, attaching labels identifying the products as vintage Navajo. Note the jewelry pieces, a definite “no no” on the rez and according to federal law … in the entire United States! Fashion faux pas? Mais oui, C’est une grande wtf.

The Navajo Nation included this screenshot in their legal filing. Of course, if you search for the Navajo descriptor now, nothing comes up.

But look at what is still up at Free People:

And it’s in stock for a mere $498!

-navajo with a h/t to Lauren Chief Elk

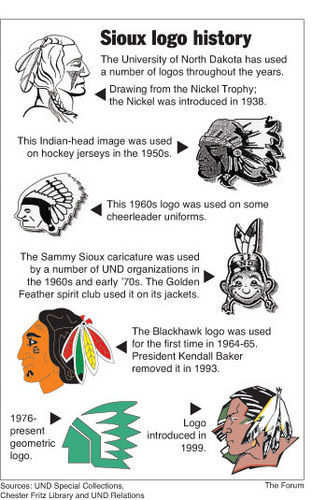

“Fighting Sioux” Fight in North Dakota Gets Hotter Still

The conflict over the “Fighting Sioux” nickname and logo at the University of North Dakota that we have been reporting on for a few weeks not cooled. On the contrary. Here is the latest news:

• The NCAA has told university officials not to allow its sports teams to bring the “Fighting Sioux” nickname and logo of a Lakota Indian head to any playoffs. The university was in the process of buying new uniforms without the logo as a result of the NCAA’s 2006 rule against such nicknames. But state legislators and supporters of a referendum to keep the name have complicated the situation.

• The University of Iowa has gone a step farther and denied UND an invitation to a track meet. UI’s policy “prohibits the athletics department from scheduling competition with schools or attending tournaments hosted by schools using American Indian mascots unless those mascots have been approved by the NCAA and their respective American Indian tribes.” Previously, officials at the Iowa school had continued competing with UND, but the delay in removing the name finally spurred those officials to begin enforcing university policy.

• Students at the University of Minnesota-Duluth have been warned they will be ejected from any future games if they again behave as they did during a recent hockey game with UND. Several students taunted the North Dakota team with war-whoops as well as chants of “Smallpox Blankets!” and “Hi, HOW are you?” The UMD athletic department stated in the letter that students would be ejected at any future games and have their season tickets voided if they engage in such racist behavior in the future.

• Meanwhile, some supporters of a statewide initiative to keep the “Fighting Sioux” nickname and logo are threatening to start a second initiative that would get rid of the state’s Board of Education and replace it with a single elected higher education commissioner. That move comes in response to the board’s decision to seek a ruling from the state supreme court about the legality of a law the initiative backers want to reinstate. The law requires that the “Fighting Sioux” nickname be kept. It was passed in February last year and repealed in November and then reinstated again until the initiative is decided by the voters.

The board of education majority says the legislature overstepped its authority in the matter, but its members said they are not trying to subvert the legislature’s authority in general. “With the current board, there is no accountability,” Sean Johnson, of Bismarck, told a legislative higher education oversight committee on Friday. “We need to have accountability, and we don’t have it.”

Opponents of the idea say they think it is a bad idea to replace a board with a single commissioner. Some elected officials say it would be better to have a commissioner appointed by the governor.

-Meteor Blades with a h/t to betson08

• Oklahoma Taking Steps to Bring Jim Thorpe’s Body Home: Olympian Jim Thorpe (Sac & Fox) was buried in Pennsylvania in a town he never visited while alive. His last wife took away his body during his funeral to spite the governor of Oklahoma who refused to fund a memorial. Thorpe’s family is suing under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act to have his body returned to the reservation.

-navajo

• Mariah Watchman competes on America’s Next Top Model: ANTM features the 20-year-old Watchman (Ojibwe/Modoc/Mandan) as the Pocahontas stereotype. The 20-year-old model from the Umatilla reservation in Oregon turns their racism into an opportunity to give back to Indian Country.

-navajo

• Minnesota Redistricting Could Boost Indian Voting Clout: The Minnesota Supreme Court has ordered a new redistricting plan that could lead to the election of a Red Lake or Leech Lake band member to the Minnesota Legislature because it will include entire entire reservations within legislative districts. And that would be good for the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party since Indians in the state cast their ballots preponderantly for the DFL.

-Meteor Blades

• Adopted Cherokee Baby Returned to Father Under the Indian Child Welfare Act: Dustin Brown (Cheyenne) won full custody of his daughter Veronica under a federal law designed to keep Indian children and their families together. Brown said he was tricked into signing papers to give her up. The adoptive family is upset.

-navajo with a h/t to Land of Enchantment

Indians have often been referred to as the “Vanishing Americans.” But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither navajo nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

nice post,thanks for sharing! BTW,check out my new android 4.0 tablet .