Until the sixteenth century the Mi’kmaq, one of the northernmost tribes on the Atlantic coast, lived a traditional lifestyle based on hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plants. Then the Europeans began to arrive, bringing with them manufactured trade goods and the illnesses of European society, smallpox and Christianity. Smallpox tried to kill the people and Christianity tried to kill the Mi’kmaq culture.

Traditional Culture:

The Mi’kmaq followed a seasonal subsistence round: their migratory pattern was to hunt inland during the fall and winter and then to spend the summer on the seashore. In the fall they would disperse into small groups to hunt moose and caribou. They also hunted partridge, waterfowl, seals, rabbit, beaver, otter, and porcupine. In addition to using the bow and arrow, they also used deadfalls and snares in hunting.

In hunting moose, the Mi’kmaq would use birchbark callers to attract the animals. Sometimes they would make the call of a female moose and then take water in a birchbark container and let it fall from some height. The noise would make the bull moose think that a female moose was urinating, something that attracted the male.

In the spring the Mi’kmaq would gather in large groups at traditional camping places on the coast and the rivers. Here they would take advantage of the abundant shellfish, and the spawning smelt, herring, and salmon. Groups at this time might have as many as 200 people. In fishing for cod, smelt, trout, and salmon, the Mi’kmaq would use bone fishhooks and nets. Occasionally fishing weirs were used. There are some reports that the Mi’kmaq raised fish in artificial ponds.

The Mi’kmaq were a sea-going coastal people who paddled their ocean-going canoes far out into the open waters of the Atlantic hunting for whales and porpoises. Both the Mi’kmaq and Beothuk seagoing canoes were unusual in that they had a rise amidships which allowed the craft to be leaned over 35 degrees without shipping water. This made it possible for hunters to bring on board a 300-pound porpoise.

With regard to navigation in open water, the Mi’kmaq charted their directions by the stars, using the North Star as a stationary point of reference.

In some areas, the sea-going canoes were rigged with sails for long journeys. While the sails were sometimes made from bark, the hide of a young moose was more common. Some canoes, such as those of the Beothuk, appear to have had keels and used stone ballast, particularly when rigged with sails.

Early European Contacts:

There were only sporadic contacts with the Europeans during the sixteenth century. The first recorded contact between Europeans and the Mi’kmaq was in 1519 when European fishing boats began trading with the Mi’kmaq in what is now Maine and the Canadian Maritime Provinces. It is quite probable that there were earlier, unrecorded contacts between the Mi’kmaq and English fishermen from Bistol in the 1480s and the Vikings in the 1000s.

In 1593, Richard Strong, the captain of an English ship that was fishing off the coast of Nova Scotia, landed at Cape Breton in search of fresh water. They traveled inland and found that the Mi’kmaq had round ponds in which they were keeping live fish.

While there were relatively few accounts of contacts between the Mi’kmaq and the European invaders during the sixteenth century, it is clear that a number of Europeans visited them and perhaps lived with them for a while. In 1609, Marc Lescarbot published his Histoire de la Nouvelle-France. Lescarbot, trained as a lawyer, provided a detailed description of many aspects of Mi’kmaq life.

The Indians generally viewed the French as physically stunted, with repulsive hair on their faces and bodies. Since many could not speak the Indian languages very well, the Indians assumed that they must be mentally retarded. And finally, the French salted their food making it inedible and many of their customs, including their symbolic cannibalism, seemed utterly barbaric.

The Missionaries:

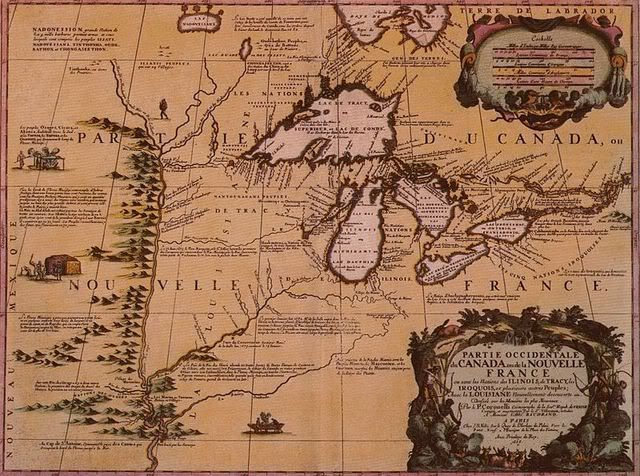

During the seventeenth century, the French claimed what they called New France under the Discovery Doctrine, a legal doctrine which states that Christian nations have a right, and possibly an obligation, to govern all non-Christian nations. While their primary concern was in making money through the fur trade with the Indians, they often justified this by claiming that they would also convert the Indians to Christianity.

In 1610, Samuel de Champlain asked the Recollets-an ascetic branch of the Catholic Franciscans-to send a missionary to work among the Indians. The Recollets did not prove to be very successful in gaining converts and were soon replaced by the Jesuits.

In 1634, the Jesuit missionary Father Julien Perrault described the unique culture of the Mi’kmaq in what is now Nova Scotia. In his report he told how they lived with the seasons, how they dressed and behaved, and what they looked like. Reflecting his Jesuit bias, he reported that

“what they do lack is the knowledge of God and of the services that they ought to render to him.”

In 1634, the Jesuit mission to the Mi’kmaq on Cape Breton Island was closed as the native population had dwindled. The Jesuits decided that Cape Breton was not a productive area for teaching and conversion. The Jesuit missionaries were sent inland.

In 1661, Father Chrestien Le Clercq, a Recollet priest, published Nouvell Relation de la Gaspésie which provided a detailed description of the Mi’kmaq (also called Souriquois and Gaspésians by other early writers). He had spent 12 years living among the Mi’kmaq, teaching them the Gospel. He learned the Native language and the people described how their nation had been settled long before by visitors from overseas.

Le Clercq notes that the Mi’kmaq had writing:

“I noticed that some children were making marks with charcoal upon birchbark, and were counting these with the finger very accurately at each word of prayers which they pronounced.”

He also notes their expertise in cartography by reporting that they had

“much ingenuity in drawing upon bark a kind of map which marks exactly all the rivers and streams of a country of which they wish to make a representation.”

In 1711, the English military took control of Port Royal from the French. This ended the French missionary work among the Mi’kmaq. Unlike the French, the English made no attempt to cultivate any good will among the Mi’kmaq and did not engage in the traditional gift-giving. This led to conflicts between the British and the Mi’kmaq.

What you noted about the difference between the French and the English approaches to the MicMaq of course is equally true of their respective dealings with the rest of the Wabanaki confederacy, and that difference accounts for the English colonies being in a French and Indian War, rather than a French War.

One major part of the difference had to do with religion. The French Jesuits took a co-opting approach, that is, ‘we also worship the great Creator Dabaldak, but call him Dieu, and we’ve learned a whole lot more about the topic’. The Puritans, on the other hand, approached the Wabanaki with ‘you pagans, forget all that nonsense, shut up, and listen to us.’

Dabi.