The policies of the United States regarding American Indians have generally been based on two interlocked approaches: ideological and theological. During the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century, Indian affairs were guided by an ideology based on the concept of private property and a theology based on Christianity. Thus the formation of Indian policies required no actual understanding of American Indians.

Multimillionaire steel baron Andrew Carnegie cheerfully pronounced that “Individualism, Private Property, the Law of Accumulation of Wealth, and the Law of Competition” were the very height of human achievement. Politicians and Indian reformers simply sought to apply these to the Indian tribes with no real understanding of tribal cultures. Privatizing Indian land through the Allotment Act of 1887 was done through adherence to this ideology. It was felt that this would force Indians into the modern world and enable them and their children to have a future. The more practical realized that this would simply separate the Indians from their land and allow large corporate interests to prosper.

By the 1920s it was obvious to the most casual observer that there were major economic, social, and health problems on the reservations. America’s prosperity was not reaching Indian people. The poverty on the reservations was undeniable to any who had even a casual relationship with them.

In 1923 an elite panel known as the Committee of 100 was convened to advise on Indian policy. The Committee supported the goal of assimilation, but called for a greater sensitivity to Indian customs and the protection of tribal land. The following year, the Committee of 100 recommended that Indian education be improved with better school facilities, better trained personnel, an increase in the number of students in public schools, and scholarships for high school and college.

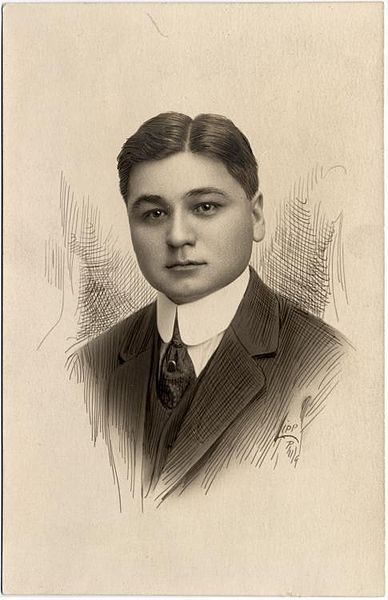

In 1926 Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work authorized an economic and social study of Indian conditions. Lewis Meriam led the study for the Institute for Government Research, a privately endowed foundation (funded by the Rockefeller Foundation). To conduct the research, Meriam put together a team of specialists from various disciplines, including some Native Americans. Henry Roe Cloud (Winnebago), a graduate of Yale University, served as the Indian adviser.

Henry Roe Cloud is shown above.

The research team conducted field work in 23 states, selected because they had more than 1,000 Native American inhabitants. They visited 95 reservations, agencies, hospitals, and schools.

In 1928, Meriam’s study entitled The Problem of Indian Administration (more commonly called the Meriam Report) was published. This was the most comprehensive study of Indian reservations ever done. The report strongly repudiated the philosophy of Indian policy which had prevailed since 1871.

While there were, and still are, many people who feel that poverty is a condition which Indian people have brought upon themselves, and that government policies can neither ameliorate nor create poverty, the report states:

“Several past policies adopted by the government in dealing with the Indians have been of a type which, if long continued, would tend to pauperize any race.”

Beginning in 1871, Indian policy in the United States had been guided by the ideology of private property, that only through private property could Indians (and all other people) prosper and that economic development should be based on small, privately owned family farms. According to the report:

“It almost seems as if the government assumed that some magic in individual ownership of property would in itself prove an educational civilizing factor, but unfortunately this policy has for the most part operated in the opposite direction.”

The report also states:

“In justice to the Indians it should be said that many of them are living on lands from which a trained and experienced white man could scarcely wrest a reasonable living. In some instances the land originally set apart for the Indians was of little value for agricultural operations other than grazing.”

The Meriam Report recognized the economic potential of Indian arts and crafts. The report recommended that the Indian Office coordinate the marketing of Indian arts and crafts so that genuineness, quality, and fair prices could be maintained. Indian arts and crafts were seen as a way of improving the social and economic conditions on the reservations.

The report also recommended that tribes be incorporated and that the tribal councils be given some decision-making powers.

The goals of Indian education during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were to convert Indian children to Christianity; to give them Christian names, particularly surnames, so that the inheritance of property could be easily traced; to provide them with the concept of greed; and to train them as laborers and household workers. Education was often carried out through boarding schools in which Indian children were forcibly removed from their homes and the influences of their cultures. With the Meriam Report the non-Indian public is made aware of kidnapping, child labor, emotional and physical abuse, and lack of health care in Bureau of Indian Affairs schools. While the report draws attention to abuses, the assimilationist po¬licies of Indian education continues for another 40 years.

The report is particu¬larly critical of the boarding schools:

“The survey staff finds itself obligated to say frankly and unequivocally that the provisions for the care of the Indian children in boarding schools are grossly inadequate.”

While Indian education has often assumed that Indians are to be trained for manual labor, the report states:

“The Indian Service should encourage promising Indian youths to continue their education beyond the boarding schools and to fit themselves for professional, scientific, and technical callings. Not only should the educational facilities of the boarding schools provide definitely for fitting them for college entrance, but the Service should aid them in meeting the costs.”

With regard to religion, the report urges the continuation of cooperation with Christian missionaries, but cautions:

“The missionaries need to have a better understanding of the Indian point of view of the Indian’s religion and ethics, in order to start from what is good in them as a foundation. Too frequently, they have made the mistake of attempting to destroy the existing structure and to substitute something else without apparently realizing that much in the old has its place in the new.”

With regard to Indian health, the report simply stated:

“The health of the Indians compared with that of the general population is bad.”

According to the report, the general death rate and the infant mortality rate were high. Tuberculosis and trachoma (a disease that produces blindness) were very prevalent. With regard to the health care services provided to Indians by the government, the report states:

“The hospitals, sanatoria, and sanatorium schools maintained by the Service, despite a few exceptions, must generally be characterized as lacking in personnel, equipment, management, and design”

According to the report, the government-run health care institutions do not provide adequate care for their patients.

Overall, the Meriam Report set the stage for a new era in Indian policy, an era in which policy could be based on actual data rather than ideological or theological fantasies. Some of the Report’s recommendations were incorporated into the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act.

Dawn broke on marblehead!