The family is a social institution that appears to be universal among humans, though the actual form of the family can vary greatly. One of the foundational aspects of family is marriage which involves the commitment of two or more individuals. With regard to a formal definition of marriage, in Culture as Given, Culture as Choice, anthropologist Dirk van der Elst writes: “It is impossible to make a single, universally applicable definition of marriage. The reason is simple: marriage has many separate functions, so different societies can emphasize different aspects—and hence not mean quite the same thing by the term.”

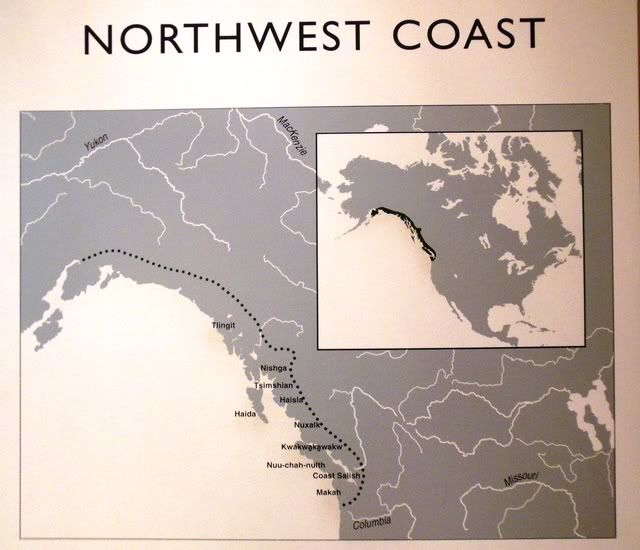

For thousands of years prior to the European invasion, Native American people lived along the northern Pacific coast between the Cascade Mountains and the ocean. Here they developed complex cultures characterized by permanent villages and social stratification (that is, there were social classes, including ruling families). As with other peoples around the world, their marriage customs reflected the other aspects of their cultures.

To understand marriage among the First Nations of the Northwest Coast, we must start with the concept of the family. While Europeans have been obsessed with the nuclear family—that is, a family composed of a man and a woman and their children—and feel that this is the foundation of human society, this type of family had little importance for the Northwest Coast Indians. For the Indian people in this region, family was about a type of extended family known as a clan.

Clans are named extended family units—that is, they include relatives which Europeans call aunts, uncles, cousin, grandparents, and so on—which often are corporate in nature (that is, they will have a formal leader and possess property) and are usually exogamous (requiring marriage outside of the clan). Among the Indian nations of the Northwest Coast, clans were traditionally the most important element of their social organization.

In the traditional pre-European villages each of the houses within the village was associated with an extended clan and each clan had certain privileges, which included fishing, hunting, and gathering rights as well as ceremonial rights (such as ownership of songs and dances).

On the northern part of the coast, among the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian, descent is matrilineal. This means that people belong to the same clan or lineage as their mother. Thus, a village leader’s position would be inherited by his nephew (his sister’s son) rather than by his own son.

Marriage was often a clan concern rather than an individual concern. Marriage united clans and formed the basis for economic and political alliances. Since marriages created alliances between houses and clans, they tended to be arranged by the families with an eye toward lasting political and social consequences. Spouses were expected to be social equals. The actual wedding was celebrated with a potlatch.

Among the Nisg’a (Tsimshian), royalty were expected to marry cross-cousins. A cross-cousin would be the child of the mother’s brother or the father’s sister. In a matrilineal system, this would mean that the cousin would not be in the same clan. Ideally, a royal man would marry his mother’s brother’s daughter, but marrying his father’s sister’s daughter was also a possibility. A royal man could marry a woman, have four children with her, then separate from her, and marry someone else.

Among the Heiltsuk, marriage was called wíná (war) and was always conducted in the style of a war party. The men from the bridegroom’s house would arrive in canoes, feigning an attack. This was the case even when the couple was from the same village. Among the chiefly classes, marriage was usually arranged by the family as it was a means of obtaining status through the transfer of names and the distribution of property. Among commoners, the couple’s wishes were the primary consideration in marriage and less wealth was transferred.

Among the Kwakwaka’wakw’ (Kwakiutl), the marriage of the eldest children of chiefs was very elaborate and was called “taking-care-of-the-great-bringing-out-of-the-crests-marriage.” Some Kwakwaka’wakw’ noble families sought to retain noble privileges by seeking out marriages within the extended family. Anthropologist Franz Boas, in his book Race, Language, and Culture, explains: “Marriages are permitted between half-brother and half-sister, i.e., between children of one father, but of two mothers, not vice-versa; or, marriages between a man and his younger brother’s daughter, but not with his elder brother’s daughter, who is, of course, of higher rank, being in the line of primo-geniture or least nearer to it.”

Among some of the Northwest Coast cultures, both polygyny (the marriage of one man to two or more women at the same time) and polyandry (the marriage of one woman to more than one man at the same time) occurred. Among the Tlingit, for example, a woman of high rank often had more than one husband, but these husbands had to belong to the same clan. Polygyny was also found among the wealthy Tlingit. While a man could marry as many women as he could afford, the first wife always outranked all others in the household.

Leave a Reply