The stereotype of the American Indian adopted by the entertainment industry and by some educational textbooks is based on the horse-mounted, buffalo hunting Plains Indians of the nineteenth century. However, the Plains Indians were not the only ones to adopt the horse and the lifestyle changes that came with it. The Indian nations in the eastern Plateau region also adopted the horse.

The area between the Cascade Mountains and the Rocky Mountains in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, British Columbia, and Western Montana is known as the Plateau Culture Area. From north to south it runs from the Fraser River in the north to the Blue Mountains in the south. Much of the area is classified as semi-arid. Part of it is mountainous with pine forests in the higher elevations.

The horse diffused into the Plateau Culture Area from the Southwest following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Shoshone, a Great Basin tribe, introduced the horse to the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Umatilla, Sanpoil, and Flathead. It is difficult to understand the impact of the horse on many of the plateau tribes. Jeremy Fivecrows, in his introduction to Alvin Josephy’s Nez Perce Country, writes: “Horses did more than modify Nez Perce culture—they transformed it, becoming our symbol of freedom and wealth.”

After learning that the Cayuse had acquired the horse from the Shoshone, the Nez Perce sent a group to trade with the Shoshone in order to acquire their own horses. According to historian Alvin Josephy in his book Nez Perce Country: “It is estimated that it took a generation for a people to become fully adjusted to the use of the horse, but in time all Nez Perce became mounted and found the horse a valuable addition to their lives.”

After the acquisition of the horse in the early 1700’s, many of the eastern Plateau tribes began seasonal buffalo hunts east of the Rocky Mountains on the Great Plains. Horses became an important economic asset as well as a symbol of prestige. The horse brought many of the Plateau tribes into close contact, and conflict, with the tribes of the Northern Plains. As a result of this increased contact, many cultural elements diffused into the Plateau. Theordore Stern, Martin Schmitt, and Alphonse Halfmoon, in an article in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, write: “With the new life, they avidly took on the fashions and accoutrements of the Northern Plains, while retaining an underlying Plateau descriptiveness.”

The diffusion of the horse into the Plateau Culture Area involved more than the animal itself: it included the Spanish patterns of riding and caring for the horse. It also included knowledge of breeding. Several of these tribes, such as the Nez Perce, the Coeur d’Alene, and the Cayuse, acquired reputations as outstanding horse breeders. Sandra Broncheau-McFarland, in her University of Idaho Master of Science Thesis, writes: “The Nez Perce were practicing selective breeding by contact time and may have been the only tribe to do so on the continent.”

According to anthropologist Colin Taylor, in his chapter in The Native Americans: The Indigenous People of North America: “Eliminating the poorer stallions by castration, the Nez Perce became justly famous for the superior speed and endurance of their horses, amongst the most distinctive of which was the traditional war-horse, which came to be known as the Appaloosa.”

On the other hand, anthropologist Deward Walker, in his chapter on the Nez Perce in the Handbook of North American Indians, reports: “They did not breed for particular colors such as the so-called Apppaloosa, which Nez Perce say was acquired from the Mormons in trade.” Henry Miller, writing for the Weekly Oregonian in 1861, reports: “The generality of the Nez Perces horses are much finer than any Indian horses I have seen.” He goes on to say: “A great many are large, fine-bred American stock, with fine limbs, rising withers, sloping well back, and are uncommonly sinewy and sure-footed.” Historian Alvin Josephy reports: “The Nez Perce favored and bred any color or kind of horse so long as it was swift and intelligent and pleased them.”

With the acquisition of the horse, the Plateau Indians began to manufacture elaborate and well-decorated horse trappings. These included saddles for men, for women, and for packing. Among the Klickitat, the men used a stuffed pad with wooden stirrups as a saddle. The women’s saddle was made with a high pommel and cantle. For a bridle they used a hair rope which was knotted around the horse’s lower jaw.

One of the first Plateau tribes to obtain the horse was the Cayuse. Historian Larry Cebula, in his Plateau Indians and the Quest for Spiritual Power, 1700-1850, reports: “The Cayuses in particular benefited by getting horses early and by owning some of the best grazing land in the Northwest.”

The Cayuse were well-known for their horses, not just for breeding them, but also for the care and decoration which they lavished upon them. Historian Terence O’Donnell reports in Idaho Yesterdays: “In particular they valued white horses; to them they would attach feathered headpieces, streak their withers with dyes of different hues, and braid their tails with colored ribbons.”

The horse also became important for trade. Anthropologist Deward Walker writes: “From the beginning of the nineteenth century, Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Flathead possessed more horses than most tribes of the northern Plains, helping create an extensive trade in horses with Plains groups like the Crow who routinely met to trade horses and other items with Plateau groups.”

Not only did the horse become an item of trade itself, but as a new means of transportation it changed the trade routes. For thousands of years prior to the horse people had followed the rivers as their highway to trading areas. With the acquisition of the horse, this began to change and overland travel was now easier. This meant that areas which had once been peripheral to trade became more important and some areas, particularly those which were well-forested and more suited to canoe travel than to horse travel, became peripheral.

The horse also brought a change in the settlement patterns. After the acquisition of the horse, village sizes tended to increase and villages were more likely to be located in areas which could provide both protection and feed for the large horse herds.

In some instances, the horse enabled tribes to extend their territories. Anthropologist Peter Carstens, in The Queen’s People: A Study of Hegemony, Coercion, and Accommodation Among the Okanagan of Canada, writes: “The horse made travel easier and quicker than by foot or by canoe, and facilitated Okanagan expansion not merely to the north, but to the east and west as well.”

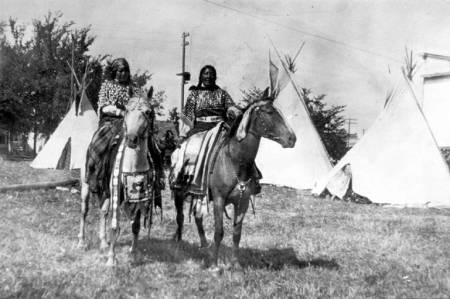

Using the horse and hunting buffalo on the Plains, a number of Plains cultural elements were acquired in the Plateau. These Plains cultural elements included the use of the tipi and the travois, the custom of war honors dances, beaded dresses, feather warbonnets, and the idea of electing chiefs because of their skill as warriors rather than selecting chiefs because of inheritance. Sylvester Lahren writing about the Kalispel in the Handbook of North American Indians, notes that: “Warfare was almost nonexistent prior to the arrival of the horse.”

A travois is two long poles which are tied together and pulled by horses. Cross-poles lashed to the long poles form a bed on which a family’s belongings can be carried. The Kootenai, living in mountainous country, never used the travois.

Leave a Reply