During the nineteenth century there were a number of religious movements that developed among diverse Indian tribes. One of these, called the Ghost Dance by non-Indians, arose among the Paiute in Nevada.

In 1868, Paiute healer Fish Lake Joe, also known as Wodziwob, had a dream which empowered him to lead the souls of those who had died in previous months back to their mourning families. Wodziwob already had the power to lay next to a patient, send his soul out, and bring the patient’s soul back to the body, thus restoring life.

Wodziwob experienced a series of visions in which the destiny of the Indian people was revealed to him. In his first vision, which occurred during a fast in the mountains, he saw the earth swallowing up the Americans. In a second vision, he saw the Americans being killed by an earthquake. In a third vision, he was told that only the believers would be resurrected.

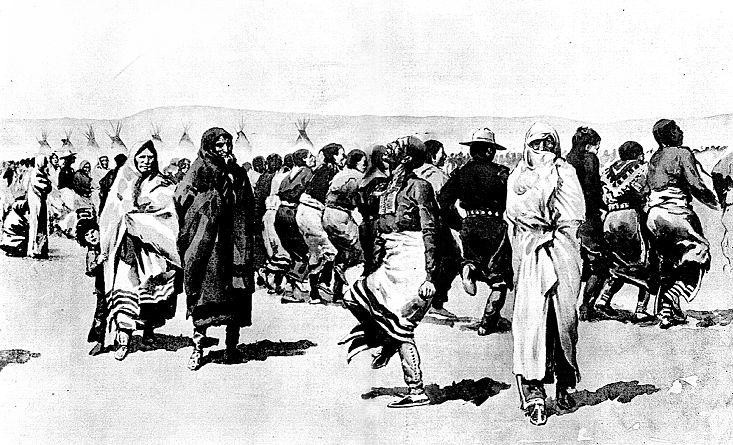

He also saw in his visions a new dance. It called for men, women, and children to join in alternating circles of males and females dancing to the left with fingers interlocked with the dancers on each side. The dance was to be performed for at least five nights in succession. During the dance, some of the dancers would receive visions giving them new songs and ultimately would restore Indian resources. The new dance quickly spread to the northern California tribes.

The new spiritual movement was called the Ghost Dance (not be to confused with the Ghost Dance of Wovoka which spread to the Great Plains and resulted in the massacre at Wounded Knee).

The following year, Wodziwob announced his expanded powers to bring back the souls of the dead. Since he already had a reputation for being able to bring back the souls of those who had recently died, his message was favorably received.

He exhorted the people to paint themselves and to dance the traditional round dance. In this dance men, women, and children joined in alternating circles of males and females dancing to the left with fingers interlocked with the dancers on each side. As the dancers stopped to rest, Wodziwob fell into a trance. When he returned he reported that he had journeyed to the land of the dead, he had seen the souls of the dead happy in their new land, and that he had extracted promises from them to return to their loved ones in perhaps three or four years.

The dance was to be performed for at least five nights in succession. The dancers decorated themselves with red, black, and white paint. During the dance, some of the dancers received visions which gave them new songs and which they felt would ultimately restore Indian resources. The new dance quickly spread to the northern California tribes.

Wodziwob’s Ghost Dance religion represented a radical departure from the religious traditions of the Great Basin. It represented a synthesis of the traditional Paiute belief in visions, and the traditional practice of circle dancing associated with antelope charming and other subsistence pursuits. It also seems to borrow from Sahaptian or Salishan Indians of the Plateau and Northwest Coast in the belief in prophets, prophecies, and return of the dead.

In 1870, Wodziwob (also known as Tavibo) was visited by Indians from Oregon and Idaho. The Shoshone and Bannock from Idaho’s Fort Hall Reservation and the Shoshone from Wyoming’s Wind River Reservation became active proselytizers for the new religion and sponsored a number of Ghost Dances. Among those attending these dances were people from the Ute, Gosiute, and Navajo tribes.

At this time, the Ghost Dance also began to move into California. The Modoc brought word of the Ghost Dance to the Shasta.

In 1871, Wodziwob’s Ghost Dance spread from the Paiute in Nevada to a number of California tribes, including the Washo, Mono, Modoc, Klamath, Shasta, Karok, Achumawi, Northern Yana, Wintun, Hill Patwin, and Pomo. Mono chief Joijoi learned of the Ghost Dance from Moman, a Paiute Ghost Dance leader. Joijoi then sponsored the first Mono Ghost Dance at Saganiu and invited many other tribes to attend. Joijoi then spread the word of the dance throughout California.

The new religious movement revitalized the tribal traditions and molded itself to the local customs. While the shared core of the ceremony was a dance in which the participants held hands and side-stepped in a sunwise (clockwise) fashion, each of the tribes adopting the ceremony modified it to fit their own cultural traditions. The Ghost Dance was instrumental in reshaping native shamanism and it helped native Californians withstand pressures to adopt Christianity.

In 1871, the Ghost Dance was introduced to the Siletz and Grand Rhonde Reservations in Oregon by the California Shasta.

In 1872, the Ghost Dance diffused from the Paiute in Nevada to the Pomo in California. The new religious movement was brought to the Pomo by Lame Bull, a Patwin prophet and a Southwestern Pomo called Wokox. Among the Pomo, the Ghost Dance became a revivalistic movement that promised its followers that the American invaders would be killed by a natural disaster. Following this, the traditional Indian ways would return again.

In 1872, the Paiute had now been dancing under the direction of Wodziwob for four years. At this time, he had another dream in which he realized that the souls of the dead which he had seen were only shadows. With horror, Wodziwob realized that his prophecy was no more than a cruel trick of the evil witch owl. He confessed his sad disillusion to the Paiutes, and they ceased dancing to attract back their loved ones. Wodziwob died shortly after this.

While the Ghost Dance inspired by Wodziwob’s vision failed to bring back the dead, it did result in a new determination to maintain Indian culture and to establish new ways compatible with the contemporary world. The tribes that incorporated the Ghost Dance worked out new ceremonies, amalgamations of old, borrowed, and newly invented rituals, and made these the center of community life.

Leave a Reply