The Potawatomi were one of several Algonquian-speaking Indian nations which inhabited the western portion of the Northeastern Woodlands culture area. Among the Algonquian-speaking people of the western Great Lakes area, farming was of secondary economic importance (hunting and gathering were of greater importance) and contributed less than half of their food. As with the other Indian farmers of the Northeast, they raised corn, beans, tobacco, and squash.

Oral tradition reports that the tribes of the Three Fires Confederacy—Ojibwa, Ottawa, Potawatomi—were once a single people who lived far to the east. At the time of separation, the tribes were living in the area around the Straits of Mackinac. The Potawatomi, considered the Youngest Brother of the three tribes, moved south into present-day Michigan. It is estimated that the three tribes may have separated as late as 1550.

The name “Potawatomi” means “people of the place of the fire” and in the historical records may be spelled as “Potawatami,” “Pottawatami,” and “Pottwatomie.” It is pronounced pot-uh-WOT-uh-mee. The name comes from Bodewadmi, the Ojibwa designation for them.

The early French explorers report that the Potawatomi occupied the southwestern portion of the lower peninsula of Michigan prior to 1640. During the Beaver Wars of the 1640s, they crossed over to the Green Bay area and by 1675 they were one of the dominant tribes of this area. During the eighteenth century, the Potawatomi occupied the area from modern Milwaukee through Chicago and across southern Michigan to the area of modern Detroit.

The Potawatomi would establish large summer villages on the edge of the forest. The villages would be convenient to streams and lakes and near prairies. Here they would plant their crops of corn, beans, tobacco, and squash. Each summer village contained several clans. The population of Potawatomi summer villages ranged from 50 to 1,500 people.

In the late fall, the large Potawatomi summer village would disperse and the people would settle in smaller hunting camps located in sheltered valleys. Then in the spring, the people would come back together again.

Hunting was an important economic activity and hunting territories were allocated to specific families. While these families did not own the land in the European sense of land ownership, they did have the exclusive hunting rights for a specific area. Game taken by a hunter was generally shared freely among all in the camp or village, including strangers. The purpose of hunting was to feed the people, not just the hunter and the hunter’s immediate family.

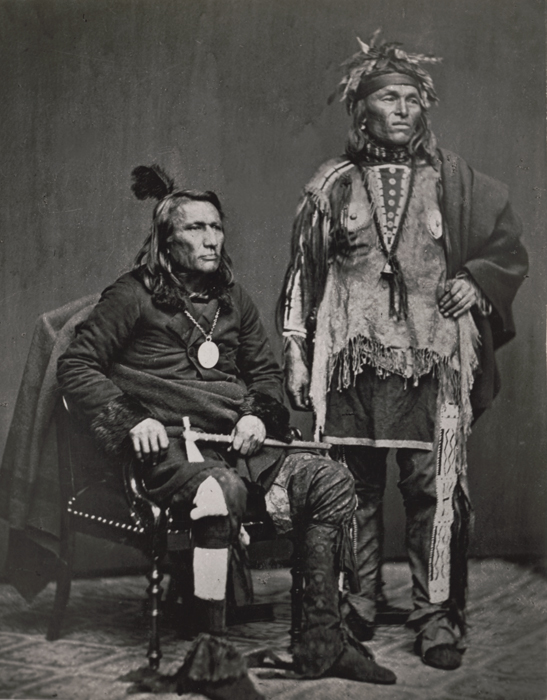

Concerning Potawatomi dress and adornment, historian David Edmunds, in a chapter in An Anthology of Western Great Lakes Indian History, reports:

“The Potawatomis took great pride in their personal appearance, elaborately ornamenting their hair and bodies.”

Among the men, hair was worn long except during war when the head was shaved, leaving only a scalp lock. Potawatomi women wore their hair in a single braid down the back. Both men and women wore earrings and bracelets.

Concerning men’s clothing, Josephine Paterek, in her book Encyclopedia of American Indian Costume, reports:

“Anciently, the Potawatomi men did not wear a shirt, but by the time of European contact, they were wearing unseamed pieces of tanned skin for shirts.”

With regard to Potawatomi women’s dress, Josephine Paterek reports:

“The women’s dress consisted of two pieces of tanned deerskin fastened at the shoulders and at the side, reaching to below the knees, sometimes belted.”

Throughout the western portion of the Northeast Culture Area, the numerous lakes, rivers, and streams served as highways for the people. This meant that the people used canoes as a major form of transportation. These canoes were made with a wooden frame which was covered with birch bark. The birch bark was reinforced with pine or spruce gum. In the winter, they would bury their canoes so that they would not snap in the intense cold.

Among the Potawatomi, the larger bark-framed canoes—which were up to 25 feet long and 5 feet wide—could only be owned by a member of the Man clan or by someone who had been given the power to own this type of canoe in a dream.

The Algonquian-speaking groups in the western portion of the Northeastern Woodlands were patrilineal; that is, they emphasized descent through the male line. People were members of their father’s clan.

Among many of the tribes of the region, marriage for some high status individuals was an arrangement between two families which created bonds and obligations. For most people, marriage was simply an informal union agreed upon by the couple without any guidance from their relatives. A woman’s status or social standing within the tribe, by the way, was not determined by her husband’s status.

As with other tribes in the area, polygyny—the marriage of one man to more than one woman at the same time—was acceptable. Among the Potawatomi, sororal polygyny—one man having two or more sisters as wives—was the preferred form of marriage. Marriage usually involved the formal exchange of property between the clans. With a first marriage, the couple would live with the wife’s family for about a year and then they would move back to the husband’s village. During this year, the husband would provide for the wife’s family by hunting and caring for the horses.

The Potawatomi favored cross-cousin marriage: a man would marry the daughter of his father’s sister or of his mother’s brother.

A Potawatomi child would be given a name about a year after birth. This name would be selected from available clan names and would thus connect the child to the clan.

With regard to the government of the Potawatomi villages, anthropologist James Clifton, in his chapter on the Potawatomi in the Handbook of North American Indians, writes:

“The leader was aided in the tasks of governance by a council of adult males, who would express public opinion and their own interests, validate decisions, and exercise the real authority necessary to back them up.”

While the Potawatomi village chief usually came from one clan, the position was not inherited. Instead, the village council would select the chief from several possible candidates. The actual power of the chief was determined by personal influence as the chief held no formal authority. Part of this influence rested on the spiritual power which the chief controlled.

The Potawatomi also had females chiefs, including several who signed treaties with the United States.

Each Potawatomi clan owned a sacred bundle which embodied the clan’s spiritual power. Anthropologist James Clifton reports:

“Each clan had associated with it a sacred bundle, an origin myth of the bundle, and a set of songs, chants, and dances.”

The origin myth for the bundle tells how a named individual received the bundle and its spiritual powers in a vision.

The Potawatomi buried their dead with the graves oriented in an east-west direction. The burials were elaborate and the body interred with grave goods, tools, weapons, and food. Anthropologist James Clifton describes a burial:

“The body was dressed in best clothing and laid out with both necessary and precious possessions: moccasins, rifle, knife, money, silver ornaments, food, and tobacco.”

Historian David Edmunds reports:

“The Potawatomis believed that departed souls traveled to the west, beyond the sunset, and were assisted on their journey by Chibiabos, a mythological figure who guided them to heaven.”

The members of the Potawatomi Rabbit clan were cremated rather than buried.

Leave a Reply