Linguists studying and comparing languages throughout the world have noted that some languages are similar to each other in terms of vocabulary, sound patterns, and grammatical structure. Using these comparisons, they group languages into language families. According to linguists Laurence C. Thompson and M. Dale Kinkade, in their chapter on languages in the Handbook of North American Indians:

“Language families are groups of languages that can be shown to be genetically related, using techniques developed by comparative linguistics.”

In North America, linguists generally recognize 58 language families and isolates. While there have been some attempts to group most American Indian languages into a single “superstock” called Amerind, Victor Golla, Ives Goddard, Lyle Campbell, Marianne Mithun, and Mauricio Mixco, in their entry on North America in Atlas of the World’s Languages, write:

“Amerind is rejected by nearly all specialists in Native American languages. They maintain that valid methods do not at present permit reduction of North American Indian languages to fewer than 58 independent language families and isolates.”

Understanding language families is one of the keys to understanding the historical relationships between the Indian groups. Anthropologist Ruth Underhill, in her book Work a Day Life of the Pueblos, writes:

“When we know the language of an Indian group, we have a clue to its history.”

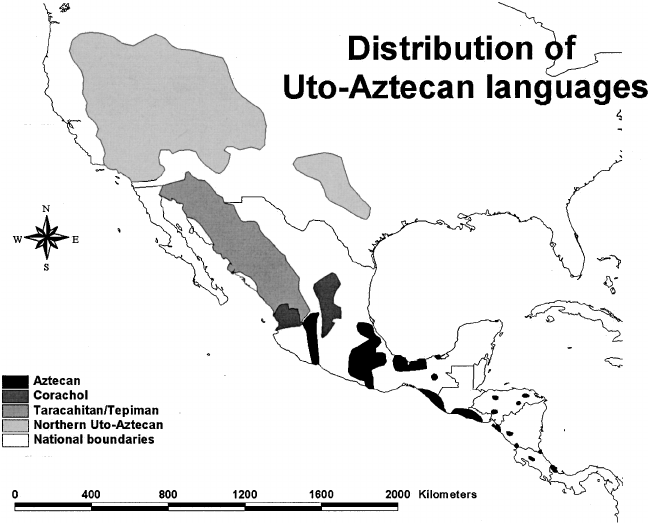

The Uto-Aztecan language family is one of the largest language families in the Americas. The Indian nations whose languages belong to this family are found in the Southwest, in California, in the Great Basin, and in Mexico.

Regarding the diaspora of Uto-Aztecan speakers into the Southwest and the Great Basin, Stephen Hirst, in his book I Am The Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People, reports:

“Speakers of Uto-Aztecan languages appeared in the Southwest more than 3,000 years ago, possibly from southern Mexico and Central America. The northernmost of these Uto-Aztecan speakers dispersed into the Great Basin as Utes, Paiutes, Gosiutes, Bannock, and Shoshone, gradually displacing the Hokan [a language family] occupants westward toward the mountains and deserts.”

In an article in Utah Historical Quarterly, Catherine and Don Fowler report:

“Archaeological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Numic-speaking peoples spread across the Great Basin sometime after A.D. 1000, displacing or replacing the earlier carriers of the Fremont and Virgin Branch Anasazi cultures in Utah, eastern Nevada, and Northern Arizona.”

Divisions of languages within a language family are called sub-families, groups or sub-groups. Some of the divisions of the Uto-Aztecan language family include:

Takic

This California group includes Serrano, Tataviam, Cahuilla, Kitanemuk, Gabrielino, Cupeño, and Luiseño.

Tubatulabal

This is an isolated Uto-Aztecan language which was spoken by 1,000 people in California’s upper Kern River Valley. According to linguist William Shipley, in his chapter on the Native languages of California in the Handbook of North American Indians:

“The distinctiveness of Tubatulabal speech points to its being an older idiom in California than the other Uto-Aztecan languages.”

Numic

This Great Basin group can be broken into three sub-groups:

Western Numic includes Mono, Paviotso, Bannock (Northern Paiute), and Gosiute

Central Numic includes Panamint (Timbisha), Shoshone, and Comanche.

Southern Numic includes: Mohave, Paiute, Ute, Kawaiisu, and Chemehuevi.

With regard to Central Numic, in 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau counted 2,284 Shoshone speakers and ranked the Shoshone language 18th in the number of speakers of American Indian languages. In their book An Introduction to the Shoshoni Language: Dammen Daigwape, Drusilla Gould and Christopher Loether write:

“These figures are not accurate because only 12 percent of the population in any one area were questioned concerning language use.”

In Shoshone there are some differences between male and female language. Men and women may use different words in referring to the same object. There are also differences when a male is talking to a woman, and vice-versa.

Verbs describe action. Drusilla Gould and Christopher Loether report:

“Shoshoni verbs are very different from English verbs, and there is no one-to-one correspondence between tenses in Shoshoni and English.”

On the Southern Plains, Comanche was often used as the language of trade and diplomacy. Historian Pekka Hamalainen, in his book The Comanche Empire, reports:

“Native oral traditions attest that Comanche challenged sign language as the universal language of exchange.”

Sonoran

The Sonoran language group includes Pima, Papago, Hopi, Huichol, Yaqui, Cora, Mayo, and Tarahumara. These languages are spoken in the northern Mexican states as well as in Arizona.

Pima (Akmil O’odham) and Papago (Tohono O’odham) are closely related and sometimes grouped as O’odham.

Some linguists, such as Harry Hoijer in his introduction to Linguistic Structures of Native America, group Hopi as a part of the Shoshonean or Numic sub-family rather than as a part of the Sonoran sub-family. Some linguists place Hopi in its own category within Uto-Aztecan. Geographically, it is far north of the other Sonoran languages and closer to the Shoshonean language areas.

With regard to Hopi, linguist Ekkehart Malotki, in his book Kokopelli: The Making of an Icon, writes:

“At least three Hopi dialects, whose differences in terms of pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary are relatively minimal, can be distinguished. No prestige dialect exists.”

Benjamin Lee Whorf, in his report on Hopi in Linguistic Structures of Native America, reports that there are four slightly differentiated Hopi dialects: Polacca, Toreva, Sipaulovi, and Oraibi. Benjamin Lee Whorf describes the language this way:

“Hopi is an ‘inflectional’ language with many specialized parts of speech and a technique partly analytic and partly synthetic, the latter largely of suffixation with suffices often fusing together but seldom fusing with the stem, and with a moderate degree of stem-alteration by stress shift and change or elimination of the first vowel, and a very little prefixing.”

Nahuatlan (Aztec)

The Nahuatlan language group is also called Aztec and includes a number of closely related and mutually intelligible dialects spoken in Central Mexico. Benjamin Lee Whorf, in his report on Aztec in Linguistic Structures of Native America, reports that Aztec, with regard to the number of native speakers, is the largest Native language in the Uto-Aztecan language family. Whorf goes on to say:

“For that matter, it is the largest native language of North America, approached only by Maya in size.”

Benjamin Lee Whorf also reports:

“Aztec is a highly inflecting language using both prefixing and suffixing, the latter to the greater extent, with little internal change and that incidental to affixing process.”

This allows the speakers of the language to coin new words fairly easily. By the time of the Spanish invasion, Aztec had an enormous vocabulary with an extensive system of religious, philosophical, and abstract terms.

Benjamin Lee Whorf writes:

“Phonetically simple, morphologically it is complex by the standard of Western European tongues, yet it is one of the simpler Utaztecan languages on this score.”

Mexican Spanish has borrowed heavily from Aztec. Some of the English words which have been borrowed from Aztec include: tomato, chocolate, avocado, coyote, and ocelot.

Feel free to use or set a link to my Uto-Aztecan Comparative Vocabulary 2011, now available online, /https://utoaztecan.blogspot.com/