( – promoted by navajo)

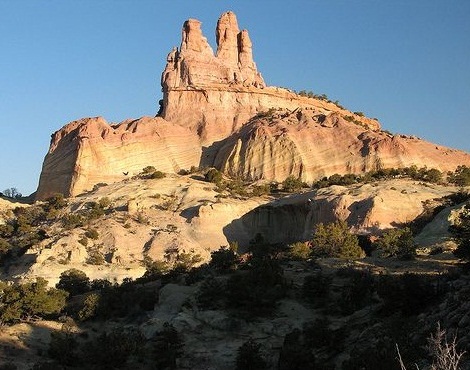

On the morning of July 16, 1979, Church Rock (just east of Gallup, NM and north of I-40) was a small sun baked community of mainly Navajo (Dine’) people, herding sheep or growing a little corn amidst red dirt and sagebrush. Clusters of traditional hogans (eight sided cabins) and mobile homes can be seen from the roads throughout the region, marking family land allotments.

Behind an earthen pond dam, ninety million gallons of liquid radioactive waste, and eleven hundred tons of solid mill wastes were sitting in a pond waiting for evaporation to leave behind solids. Suddenly, the dam gave way and the waters burst through, flowing out across the red land, and down the washes to permanently contaminate the Rio Puerco, known to traditional Dine’ as To’ Nizhoni (beautiful water.) This may look like a large dry wash to people passing over it at 80 miles an hour on the interstate. There is water mostly when there are thunderstorms in the watershed or when the winter snow melts up in the mountains. There are not a lot of people living out here. You can see a long way when the interstate tops a rise, and you can see a great empty distance with long train tracks. When the freight trains come through, they bear logos like MAERSK, China Shipping, Costco. Consumer goods bound for the big box stores elsewhere.

Today, although few tourists stopping at the massive Route 66 casino and tourist/truck stop complex know about it, the Church Rock accident is acknowledged as likely the largest single release of radioactive contamination ever to take place in U.S. history (outside of the atomic bomb tests). A few weeks after it occurred, the mine and mill operator, United Nuclear Corporation, was back in business at Church Rock as if nothing had happened.

I lived on the Navajo Nation for several years, at Tsaile, Az near Lukachukai – over the mountains to the north and west of Church Rock by maybe 80 miles as the crow flies. I came to know several families that had been affected by uranium mining.

There are still miners, now in their 80s and 90s who are suffering the effects and bearing witness to those that know them.

The reason that the Navajo Nation banned uranium mining a couple of years ago was primarily because of the complete and utter disregard for Navajo people that mining has brought with it. That doesn’t seem to have changed, as companies with recent proposals seem to think that just ghastly after effects will be much more tolerated among Navajos than anywhere else.

Recently, there have been proposals to use volumes of water and settling ponds as a way of getting uranium out of the ground. Local meetings are held and the company dismisses concern that this will contaminate the water supply – in an area where water is terribly precious. If they proposed this with a straight face in any large urban community in the country they would get laughed out of there. Rural areas are in a terrible bind, due to lack of jobs and lack of information resources. There is also a dearth of effective advocacy on the part of elected officials, who are also from the same financially desperate environment and who may depend on mining companies for information.

One of the more amazing things I learned from being in the neighborhood was that children of the original “dog hole” miners from the 1960s and before believe that they experience second generation health impacts and worry about passing genetic damage on. The health care provider in the area is the Indian Health Service. I checked with the IHS and discovered that the federal government never did any studies assessing this.

Consistently, Indian people are treated to a great amount of disregard. If there are no studies, than the prospect that people can complain about such effects is effectively muted. That is completely consistent with the history of disregard and disrespect that Indian people have suffered at the hands of government, missionies and loads of well meaning others. These are very family oriented people. They remain closely connected with aunts and uncles, cousins, and in-law relations across the region. Experience is shared.

There are some 700 small mines still unclosed. A “dog hole” basically means one man, one shovel. The piles of dirt from these are still right where they were left. Rain causes local water to be contaminated, which is taken up by plants and eaten by sheep and cows. This can continue to create cancer risks for local people far into the future. Only recently has cleanup begun to be addressed, since interest in uranium was renewed by 4.00 per gallon gasoline.

These are not people who can move away. The land has been inherited down Dine’ family lines since at least the 1868 treaty, and possibly before that, as far back as about 1500 (maybe earlier). A legacy like that cannot be replaced.

I think the Navajo Nation was right to ban uranium mining outright. I can foresee a future in which some mining might be done again, but the problem that needs to be addressed is sufficient respect for the land and the people. What is more likely is mining companies looking for ways to force their way in, through lawsuits, and overpower local concerns just like in the old days.

Mining seems to be accompanied by a psychology that disregards and disrespects local people and the local environment and is dishonest to boot. Indian people are the last ethnic group to be considered when it comes to progress against racial discrimination. It is hard to believe it until you develop friends who are Indian and then see it through their eyes. It is just shameful that this should still be the case in 21st Century America. I am always sorry to see signs of it.

That is why Church Rock needs to be remembered.

Leave a Reply