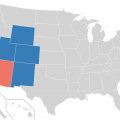

At the time of creation the Diné (often called Navajo) were instructed by the Creator that they must live within the boundaries of four sacred mountains (San Francisco Peaks, Mount Taylor, Blanca Peak, and Mount Hesperus) and two sacred rivers (San Juan and Little Colorado). Dinétah, the Navajo sacred homeland, spreads across the Four Corners region of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. While the Creator gave the Diné instructions on where to live, the United States government disagreed with these instructions, and in 1863 the Navajo were ordered to move off their sacred land.

The military commander for the U.S. Army in Arizona and New Mexico issued an ultimatum to the Navajo in 1863: they were to peacefully transfer to the reservation at Bosque Redondo in New Mexico or be treated as hostile. The military campaign against the Navajo was led by Colonel Kit Carson. Carson was directed to wage a scorched earth campaign: those who did not surrender would be left with nothing to eat. The military plan called for all male Navajos to either surrender or be shot.

In Washington, D.C., the military commander explained the strategy to his superiors:

“The purpose now is never to relax the application of force with a people that can no more be trusted than you can trust the wolves that run through their mountains.”

As a part of his scorched earth campaign, Kit Carson’s soldier’s cut down most of the 3,000 peach trees which were the Diné’s pride and joy.

The final battle against the Diné was fought in 1864 at Canyon de Chelly in Arizona. The will of the Diné was broken by their defeat and they were forced to make the Long Walk to the Bosque Redondo (Fort Sumner) in New Mexico. From the Diné viewpoint, they were leaving the protective circle of the Four Sacred Mountains and this meant that they were leaving hallowed ground. Outside of the protection of the Sacred Mountains their ceremonies would no longer be effective; the deities would not hear their prayers.

Many of the Diné died on the 300 mile forced march. According to Navajo oral tradition:

“stragglers in the procession, including pregnant women, children, and the aged, were simply shot and left unburied beside the trail”

When people complained of being sick, the soldiers simply killed them. If people stopped because they were tired, hungry or thirsty, the soldiers killed them. If a woman stopped to have a baby, the soldiers killed her and anyone who tried to help.

Their new home was a flat, barren land with poor farming conditions and alkaline water. The American plan was for the Navajo to live in adobe houses, to farm, and to develop a peaceful community life under strict military supervision. In the words of Navajo leader Armijo:

“Is it American justice that we must give up everything and receive nothing?”

The Americans assumed that their plan was a humanitarian one, but it was doomed by bad planning, the weather, and the determination of the Navajo not to be forced into settled life.

Unlike the Navajo, the Americans were accustomed to a political system which was centralized, ideally around a single individual (a dictator is often preferred) or a group of individuals. Therefore, the Americans organized the Navajo into 12 bands and appointed a chief for each one: Armijo, Delgado, Manuelito, Largo, Herrero, Chiqueto, Muerto de Hombre, Hombre, Narbono, Ganado Mucho, Narbono Segundo, and Barboncito. Barboncito was designated as the principal chief. In other words, the American government attempted to create puppet dictatorships among the Navajo.

At Fort Sumner, New Mexico, the government issued food rations to the starving Navajo. Originally, cardboard ration tickets were distributed among the people, but they quickly learned to forge these and obtained more food. The government, having discovered the forgeries, then issued stamped metal tickets, but the Navajo also learned to forge these.

After two years of captivity, 29 headmen put their marks on the “Old Paper,” and the Diné were allowed to leave the Bosque Redondo and return to their homeland. The treaty reduced the size of their homeland, but the Navajo were desperate and wanted to return home. The American government negotiated the treaty not out of any concern for the Navajo, but concern for federal dollars. It was obvious to everyone that the Navajo would never become self-sufficient at Bosque Redondo and that the government would have to issue rations indefinitely. Coupled with the costs of the recent Civil War, the government concluded that it would be cheaper to send the Navajo home.

The Diné began their return march with 1,550 horses out of the 60,000 horses which they had owned before their defeat and with 950 sheep out of the 250,000 sheep which they had before the Long Walk.

Navajo leader Manuelito is shown below:

did not go on the long walk. What a terrible, terrible ordeal for others.