( – promoted by navajo)

When Indians nations were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s they were promised, both verbally and in writing, that in this new territory their tribal sovereignty would be respected. In 1835, President Andrew Jackson said:

“The pledge of the United States has been given by Congress that the country destined for the residence of this people shall be forever ‘secured and guaranteed to them.’ A country west of Missouri and Arkansas has been assigned to them, into which the white settlements are not to be pushed. No political communities can be formed in that extensive region, except those which are established by the Indians themselves or by the United States for them and with their concurrence”

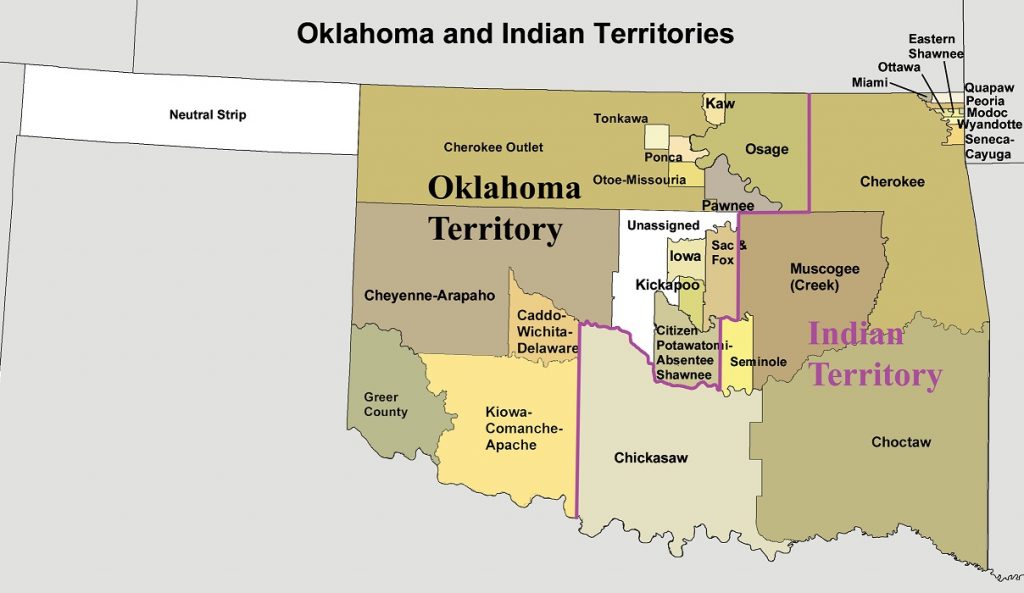

Little by little, however, their lands were reduced. Soon, the American settlers in what had been Indian Territory were talking about statehood and about the dissolution of tribal sovereignty.

The first formal step toward statehood was the passage of the Oklahoma Organic Act in 1890. Under this act, a territorial government was established and all of the Indian reservations in what had been Indian Territory were annexed into the new Oklahoma Territory.

As the Oklahoma Territory moved toward statehood in the late nineteenth century, the Territorial Legislature passed laws which began to superimpose some jurisdiction over the Indian nations within the Territory. In 1899, the Territorial Legislature prohibited the practices of Indian medicine men. Those who practiced the incantations and healing ceremonies of the medicine men were subjected to not only fines, but also imprisonment. In addition, Indians were required to be married under American law rather than Indian custom. In a move against the Native American church, the Legislature also made peyote illegal.

In 1901, all members of the Five Civilized Tribes-Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole-were granted citizenship by an act of Congress. This meant that every Indian adult male was a registered voter. This was an attempt to increase the number of voters in the territory so that it could gain statehood.

Not all Indians were happy about the push toward statehood and some Indian leaders, such as Creek chief Pleasant Porter began to advocate the idea of a separate statehood for the Indians. Porter felt that this was the only way in which Indians could truly have a voice in their own affairs. In 1902, Chief Porter called a meeting of the Five Civilized Tribes to discuss alternatives to statehood. However, only representatives from the Creek and Seminole tribes attended. Porter then called for a second meeting, which also failed.

In 1903, the Five Civilized Tribes Executive Committee passed a resolution asking each tribal council to petition Congress for statehood for Indian Territory. While some of the tribes passed such resolutions, Congress had little interest in separate statehood.

In 1905, representatives from the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Choctaw nations held a convention at which they drew up a constitution for the state of Sequoyah, which would be separate and distinct from Oklahoma Territory which was seeking statehood. The call for the convention was issued by W.C. Rogers, the Cherokee Principal Chief, and by Green McCurtain, the Choctaw chief. The issue of whether Oklahoma should be one state or two is summed up by the Muskogee Phoenix:

“There are in Indian Territory some few persons who desire two states made of the two territories and who honestly believe this can be done. There are some persons who desire conditions to remain as they now are and who know that to fight for two states is to fight for no statehood legislation, and this makes them especially active.”

The constitutional convention has been characterized as the most representative body of Indians ever assembled in the United States.

The constitution for the state of Sequoyah was submitted to the voters: the turnout was light, but the vote was strongly in favor of it. The measure was then presented to Congress which simply ignored it. Politically, there was never the slightest chance that Congress would consent to the admission of two Western states-both probably radical and probably Democratic. One state was politically a better solution in the eyes of Congressional politicians.

In order to clear the way for Oklahoma statehood, Congress in 1906 passed an Act to Provide for the Final Disposition of the Affairs of the Five Civilized Tribes in Oklahoma. In other words, Congress unilaterally dissolved five sovereign tribal governments. The Department of the Interior took over the Indian schools, school funds, and tribal government buildings and furniture. The law provided that the President may appoint a principal chief for any of the tribes. If a chief failed to sign a document presented to him by U.S. authorities, he was either to be replaced or the document could be simply approved by the Secretary of the Interior.

In 1906, Congress passed the Oklahoma Enabling Act as one step in the creation of the state of Oklahoma. With regard to Indians, the Act imposed a condition on the state constitution: Oklahoma cannot limit federal authority over Indians within its boundaries.

The state of Oklahoma was created in 1907. The tribal governments in the area were dissolved. The Indians in an area which had been promised to them as their exclusive home constituted only 5% of the population of the new state.

Unlike other western states which have often ignored their Indian heritage, Oklahoma has strongly embraced its heritage and has acknowledged its Indian population. Upon becoming a state, Robert L. Owen (Cherokee) was elected to the United States Senate. Cherokee tribal attorney and former speaker of the Cherokee House of Representatives James S. Davenport was elected to Congress.

Tribal governments continued to function after Oklahoma became a state. The Seminoles, for example, never ceased to maintain their fourteen band organizations with a chief and two councilmen from each, and these forty-two officers met once a month to discuss tribal affairs, appoint committees, and adopt resolutions. In a similar fashion, the other tribes also continued to meet, even though they no longer had formal recognition by the U.S. government.

Leave a Reply