( – promoted by navajo)

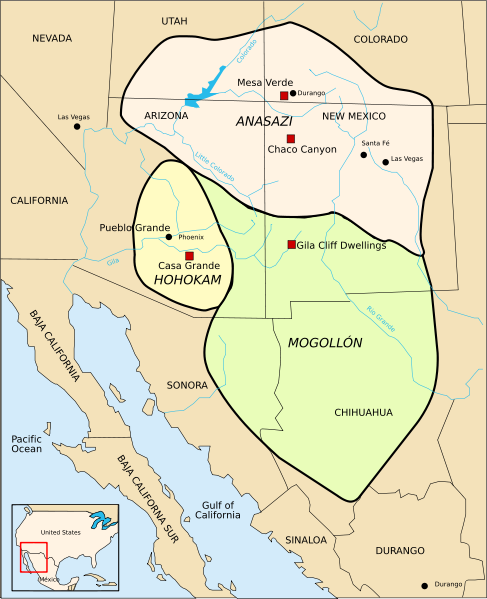

More than 2,500 years ago, American Indians brought agricultural prosperity to the Arizona desert with the construction of complex irrigation systems. About 425 BCE these Indians, the ancestors of today’s O’odham nations who are often called Hohokam by archaeologists, began construction of the city of Skoaquik which means the “place of snakes.” Archaeologists call this place Snaketown.

For more than 12 centuries the Hohokam prospered peacefully in the Arizona desert. In the Hohokam communities of Casa Grande and Pueblo de los Muertos, irrigation systems brought water to the agricultural fields from the river which was six miles away. These hand-dug canals were often ten feet deep and up to fifty feet wide. In order to prevent water loss through seepage, the Hohokam plastered the sides of the canals. These large canals fed hundreds of small ditches that brought water to thousands of acres of croplands.

In the Salt River Valley, the area currently occupied by the city of Phoenix, the Hohokam constructed more than 500 miles of fairly complex canal systems. These well-designed irrigation systems allowed the Hohokam to produce two harvests each year.

Hohokam agriculture included corn, beans, squash, agave, cotton, and tobacco. The Hohokam wove their cotton into textiles which were often used as a trade item. The Hohokam traded with the Indian nations of California as well as with those in Mexico. They also traded with adjacent Southwestern civilizations, such as the Hohokam and Mogollon.

The Hohokam towns and villages were often constructed at regular intervals along their main canals. In the Hohokam towns, such as Snaketown, most of the dwellings were built by digging a shallow pit about a foot below the surface of the desert. Vertical posts were then placed in the bottom of the pit to support slanting side poles which were covered with clay.

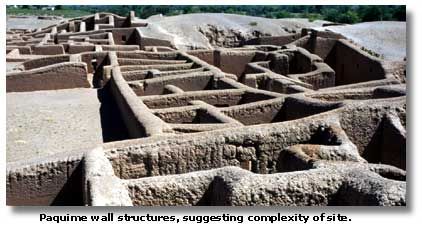

The Hohokam built some of their houses using adobe which is formed by piling up stiff mud by hand. Some of the structures, such as those at Casa Grande, rise to a height of four stories. In some of the upper rooms, there are openings which are aligned to show the positions of the sun (solstices) and there are other openings to record lunar cycles. Like other agricultural people, the Hohokam used astronomy to be able to tell the coming of the seasons and thus to plant at the right times.

At about 600 CE the contact between the Hohokam and the civilizations of Mexico intensified. During this time, the Hohokam houses became much larger and many artifacts became “mass produced”. During this time, Snaketown grew to cover nearly 400 acres.

One of the interesting features of Hohokam towns is the ball court. Similar to the ball courts found in Mexico, the ball courts have floors excavated about 20 inches below the desert floor with soil piled up on either side. There were two basic sizes of ball courts: one which was about 50 by 80 feet and one which was about 110 by 200 feet.

The game was played with a rubbery ball which players tried to knock through rings on the walls with their hips, knees, or elbows. Players were not allowed to throw or kick the ball. The game was a microcosm of the cosmos which symbolized spiritual beings trying to make the world more harmonious for humans.

Hohokam towns also had platform mounds. At Snaketown, the mound is about 50 feet across and only 3 feet high. The mound, made from clean desert soil, served as a platform for ceremonial dances and religious rituals. Over 50 Hohokam villages had large, earthen platform mounds at the center of the villages. These towns were probably religious and/or civic centers.

Like other agricultural people in North America, the Hohokam made pottery. Originally, the first settlers of Snaketown made a plain, thin-walled ware from clay coils which were pounded into shape with a flat paddle.

About 1000 CE, the Hohokam began producing etched artifacts. The artists first created a design of pitch on a sea shell obtained in trade with the tribes on the Gulf of California. It was then soaked in an acid from fermented cactus juice. The artifact was then removed from the acid, the pitch scraped off, and the result was an etched design.

Unlike other Indian people in the Southwest, the Hohokam cremated their dead. Items which were placed in the grave – such as pottery – were ritually killed by breaking them.

Sometime between 1100 and 1200 CE Snaketown ceased functioning as a village. But this doesn’t mean that the Hohokam people mysteriously vanished. The people continued to live in smaller villages along the river and continued to water their fields with irrigation ditches. The decline was created by two environmental factors: (1) a flash flood on the Salt River destroyed their diversion weir and carved the river lower, and (2) the agricultural land around the villages became saline from the irrigation and crop production fell.

Around 1300, people related to the Pueblos in New Mexico – called Salado by the archaeologists – crossed the mountains and moved into the valley. This was not a violent invasion, but a peaceful melding of the two cultures which resulted in the construction of the four-story pueblo at Casa Grande.

Today the ancestors of the Hohokam continue to live in Arizona. They are known as the O’odham.

Map:

That was a fascinating article, could someone direct me to museums online where I can view artifacts, thanks

Try these

Thanks for the llinks.

For your very informative articles!