( – promoted by navajo)

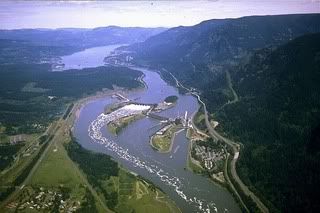

While the Army Corps of Engineers had proposed a series of dams on the Columbia River in 1929, no action was taken on this proposal until the advent of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Work on the Bonneville Dam, located 40 miles east of Portland, began in 1934 and provided much-needed employment for thousands of people. The dam was completed in 1937 and began generating commercial power in 1938. With the emphasis on the economic gains, there was little or no consideration given to the impact of the dam on the Columbia River Indians.

Construction of the dam destroyed the homes of living Indians as well as those of the dead. The Wasco village of Chief Banaha was used as the north anchor for the dam, and Bradford Island, an ancient Indian burial ground, served as its central anchor. The human remains dug up on the island were reburied by the Army Corps of Engineers in a single grave on the north shore about five miles east of the dam.

The dam is named for army captain Benjamin Bonneville who explored the Columbia River in the 1830s.

In 1937, the superintendent for the Umatilla Reservation wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs expressing concern that Bonneville Dam would flood many fishing places guaranteed to the Indians by treaty. He suggested that the Indians might have a claim to compensation. In response, the acting solicitor for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) wrote a legal analysis of the problem. He concluded that the Indians had a possible claim for compensation of the destruction of their fishing places. He suggested that the BIA negotiate a settlement with the Army Corps of Engineers and the Public Works Administration (the dam’s source of funding). In the report, the solicitor noted that the Supreme Court had ruled that fishing was not a right granted to the Indians, but an aboriginal right which the Indians had specifically retained in their treaties.

In order to document the loss of Indian fishing sites caused by the Bonneville Dam, a BIA attorney toured the Indian fishing sites on the Columbia River. Elders named the sites and the attorney meticulously marked them on the map. In addition, a BIA photographer took a photo of each site so that the changes to the site could be recorded as the reservoir filled. The Indians pointed out 27 fishing sites. The following year, the BIA returned to photograph the fishing sites which had been flooded by Bonneville Dam. The photographer found only an expanse of calm water. The sites had been flooded.

In 1938, concerned about the loss of Indian fishing sites due to the construction of Bonneville Dam, John Herrick, the assistant to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, wrote to the Army Corps of Engineers division engineer recommending that the Army buy land and construct improvements for Indian fishing stations. He suggested a meeting with the BIA and the Corps and noted:

“Later, or course, it will be necessary to bring representatives of the Indian tribes involved into the discussion….During your talks, you can decide at what point the representatives of the Indians should be brought into the picture”

Col. John C.H. Lee of the Army Corps of Engineers insisted that the War Department take no action until the tribes submitted a claim in writing. The Corps and the BIA basically agreed the claim would place no monetary value on the damage. In addition, the claim should include a request for a conference between the Army and the Indians, with the reservation superintendents included.

The following year representatives from the Warm Springs, Umatilla, and Yakama tribes met with the BIA at The Dalles, Oregon to discuss damages to fishing sites caused by the Bonneville Dam. The tribes then met with the Army Corps of Engineers. During the day-long meeting, little progress was made toward an agreement. The tribal cultures stressed the need for consensus in reaching a decision rather than a command from the top. On the other hand, the Army Corps officers, bound to the Army’s strict military command structure, could not comprehend the Indians’ way.

Two dozen traditional fishing sites would be destroyed and the Army Corps of Engineers promised to provide the Indians with six sites totaling 400 acres. Over the next 40 years, the Army Corps of Engineers actually provided only five sites and a total of 40 acres.

In 1941, the Army Corps of Engineers proposed a four-acre site along the Columbia River as an in-lieu site for the Indian fishing sites lost through the construction of Bonneville Dam. Lt. Col. C. R. Moore of the Army Corps of Engineers indicated that Indians had no say in this arrangement since they were wards of the government.

In 1947, the only in-lieu fishing site provided by the Army Corps of Engineers to make up for two dozen sites lost through the construction of Bonneville Dam was blocked by a non-Indian logger. The logger had constructed a road through the Indian housing area and was dumping logs into the White Salmon River, blocking Indian access. The Corps ordered the logging company to move, but it refused. The Corps then turned the matter over to the United States attorney for Western Washington who filed suit against the company for illegally building on government property and obstructing a navigable stream. The loggers stayed at the site.

In 1952, the Army Corps of Engineers stopped all improvement work on in-lieu fishing sites. The Corps took the position that the $50,000 appropriated by Congress in 1945 for the in-lieu sites was for land purchases only and that no improvements can be made until all of the land is purchased.

The Indians from the Mid-Columbia tribes continued to pressure the Army Corps of Engineers to obtain for them the in-lieu fishing sites which had been promised when Bonneville dam destroyed their traditional fishing sites. In 1953, the Corps found what they felt would be an ideal site at Cascade Locks. There were government buildings on the property which included sanitary facilities and the area was a part of what had been a major tribal fishing area until the construction of the Cascade Locks in the nineteenth century. Opposition to the proposed in-lieu site came from a group calling themselves the Cascade Locks Citizens Committee. The group denied that they were motivated by racial discrimination, but argued that Indians, unlike industry, would bring neither new taxable wealth nor jobs. They complained that the area selected was man-made and that the Indians had never fished in it. They were apparently unaware that the first full-scale report on Indian fishing listed the Cascade Locks as a major Indian fishing site. Freshman Republican congressman Samuel H. Coon, a staunch advocate of private power, intervened and as a result the Corps sold the land to the Port of Cascade Locks.

In 1954, the director of the Washington state department of Fisheries considered closing all commercial fishing at the Indian in-lieu sites, He stated that the Indians did not have any special fishing rights at these sites and that the state has the right to control fishing and enforce its regulations against Indian violators.

At the same time, the Oregon Fish Commission conceded that Indians had treaty-protected fishing rights at their usual and accustomed places, but these rights might not apply to other locations, such as in the in-lieu sites. The chairman of the commission states:

“We formally protest the granting of these sites to the tribes for it is our belief that the major use to which they can be put is that of fishing and fishing is a threat to the continuance of the salmon runs.”

In 1955 Congress provided the Army Corps of Engineers with an additional $185,000 for the purchase of in-lieu fishing sites as promised when Bonneville Dam was built. In addition, the money was to be used for building sanitary and other facilities. The additional funding was opposed by the Oregon Fish Commission. As the bill was working its way through Congress, the Army Corps of Engineers turned down a number of offers to obtain land for the in-lieu sites saying it didn’t need any more land. In fact, the Corps still owed the Indians two more sites and an additional 300 acres of land.

In 1959, the Army Corps of Engineers told Congress that it could do no more work on the in-lieu fishing sites. The Corps asked for a release from further efforts. Initially, the Corps had promised the Indians six in-lieu sites totaling 400 acres and in the twenty years since the promise had been made, it had actually provided them with four sites and a total of 40 acres.

In Oregon and Washington, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) issued new rules in 1969 regarding the in-lieu fishing sites along the Columbia River. Under the new rules, permanent dwellings were banned on the sites and only campers, trailers, tents, and tipis were allowed. Any structures left on the sites were to be demolished by the BIA. The Indians protested the new rules and reminded the BIA that they had lived permanently at the sites which had been flooded by Bonneville Dam. In response the BIA asked the solicitor for the Department of the Interior for an opinion on the ban and was informed that the ban was legal. According to the solicitor, the Indians’ off-reservation rights were limited to taking fish and erecting temporary buildings for curing them.

In 1970 the Corps of Engineers proposed raising the level of the Bonneville Dam pool by three feet to help meet the need for more electricity. The proposal would flood many of the Indian in-lieu fishing sites. Two years later, the Columbia River tribes learned about the proposal. The Indians responded with fear and anger. In one meeting, the attorney for the Native American Rights Fund stated:

“The Corps is becoming the cavalry of the twentieth century, driving the Indians literally into the river.”

The Umatilla tribes filed a suit asking that the Corps be barred from raising the pool. Judge Robert C. Belloni granted a temporary injunction and told the Corps and the tribes to negotiate. While the Corps of Engineers was planning a project to destroy the in-lieu fishing sites, the BIA was trying to improve them.

Congress finally stepped in again and in 1988 passed a bill which required the Army Corps of Engineers to provide in-lieu fishing sites on the Columbia River to total 360 acres (thus meeting the original promise made to the Indians.) Under the provisions of the bill, the Corps was to improve all in-lieu fishing sites, both new and old, to National Park Service standards for improved campgrounds. The Corps was to acquire at least six sites adjacent to the Bonneville pool.

The following year, the Columbia River tribes put together a task force composed of leading elders to deal with the Army Corps of Engineers in identifying and obtaining in-lieu fishing sites as mandated by Congress. The Corps, on the other hand, simply assigned a park ranger to the task force. The ranger admitted that he knew nothing about the issue and that he had no authority to speak for the Corps. The tribes asked for the Corps to assign someone with authority to the task force. The Corps then assigned a civilian planner to the force. One tribal attorney would later recall:

“We had to tell them the history of the legislation and the background over and over again.”

One of the concerns of the tribes was the sensitive handling of human remains, funerary objects, and other cultural artifacts. Many Indians were bitter about the way in which state and federal governments treated Indian graves. In 1991, the tribes initiated discussions with the Army Corps of Engineers regarding the management of cultural resources at the proposed in-lieu fishing sites. The following year, the Army Corps of Engineers issued a draft proposal on dealing with cultural resources on the in-lieu fishing sites. The tribes found the proposal unacceptable as it failed to comply with either federal historic preservation requirements or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

By 1993, the Columbia River tribes were frustrated with the lack of action on the in-lieu fishing sites and so tribal leaders went to Washington, D.C. Unannounced they arrived at the Army Corps of Engineers headquarters and told the receptionist that they were there to meet with high-ranking officials. They were ushered in to a meeting in progress about other issues. Assuming that they were part of the agenda, they were seated at the table. For an hour and a half the tribal leaders lectured startled Army brass on Indian treaties and the Corps’ responsibilities under those treaties and the law. While the Corps officers were impressed, they did not take any action.

Leave a Reply