( – promoted by oke)

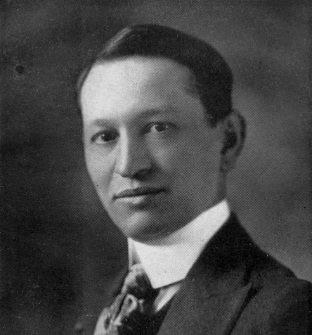

There was a time, particularly during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when museums were simply “cabinets of curiosities” which displayed artifacts from other cultures and made little attempt to educate or engage the people who looked at them. Items were displayed simply as “curiosities”: exotic items from strange people. During the first part of the twentieth century a new approach to museums was developed by Arthur Caswell Parker.

Arthur Caswell Parker was born on the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation of the Seneca Nation of Indians on April 5, 1881. His father was Seneca and his mother was non-Indian. His uncle was Ely Parker, the first Indian Commissioner of Indian Affairs and Civil War Union General.

The Seneca (The Great Hill People), whose homeland is in New York, are one of the five Iroquois nations that joined to form the League of Five Nations. One of the most important features of these five nations is their matrilineal clans: individuals inherit both their clan and their tribal status from their mother.

Since Arthur Parker’s mother was non-Indian this meant that he was not born into a Seneca clan and for this reason he was not enrolled as Seneca. However, in 1903 he was formally adopted by the Seneca Bear Clan and given the Seneca name Gáwasowneh (Big Snow Snake).

From a Seneca perspective, Parker was not Seneca, but from the non-Indian view he was considered to be Indian because: (1) his father was Indian (Americans tend to reckon descent through the patrilineal line), (2) he grew up on a reservation, and (3) he looked like an Indian. However, in American society he was not a citizen because he was Indian. Thus Parker occupied an interesting position between the Seneca world (where he was not an enrolled Seneca because his mother was not Seneca) and the American world (where he was not a citizen because his father was Indian).

There were many dimensions to Parker’s life: he was an archaeologist and was active in influencing American archaeology; he was a museum curator who brought about a revolution in the way in which museums organized their displays; he was a Mason and achieved the highest honors of that organization; he was active in pan-Indian organizations and worked towards the assimilation of Indians into American life; he was the author of children’s books which were based on Indian lore and Indian characters; he was the author of books on Iroquois history and folklore; he was a magazine editor.

Parker saw museums as integral to American democracy because they encouraged good citizenship. He advocated the idea that museums should be accessible to everyone and viewed them as the university of the common person. He promoted an interactive relationship between exhibits and the museum visitor and insisted that museums cultivate a set of concerns with which the visitors could relate.

Parker wrote:

“People want to be entertained by exhibits, sights and sounds. They want sensory stimulation. They want to be thrilled by what they experience in a museum, not merely bored by long labels and crowded cases. People want to painlessly absorb stimulating knowledge, a knowledge that makes them talk about it.”

While working at the New York State Museum from 1906 to 1915 Parker created a series of six dioramas depicting Iroquois life. The dioramas, recognized as the finest exhibits of their kind in the country, attracted over 200,000 visitors per year. To make sure that the dioramas were accurate, Parker had artists and sculptors use models with features and facial figures that conformed with typical Seneca types. He also employed many Indians from New York and Canada to carefully reproduce the clothing and artifacts for each of the scenes. Even the backgrounds in the dioramas were based on artists’ impressions of actual archaeological sites.

The dioramas provided illustrations of the various stages of cultural evolution as expressed in the anthropological theories of Lewis Henry Morgan. According to Morgan, there were various stages of cultural evolution: Savagery (Lower, Middle, Upper), Barbarism (Lower, Middle, Upper), and finally Civilization. In particular, Morgan put forth the idea that Civilization requires the monogamous nuclear family and private property. Under this scheme, Indians were placed in either Upper Savagery or Lower Barbarism, depending on their material and political development.

The exhibits were extremely attractive to the general public, but Parker did not envision them having any specific educational role for Indians. Rather, their function was to educate the wider public on the Indian’s role within the American past.

While museums present Indian life as it was in the past, Parker was also concerned with Indians in the present. In 1920 Parker addressed the New York Indian Welfare Society. He told them:

“To the white man an Indian is only an Indian if dressed in feathers and buckskins.” Pointing out that American society does not allow Indians to change, he asked: “How would the white man like it if the Indians demanded that all white men who came upon their reservations must dress in Colonial uniforms and appear like the picture of Sir Walter Raleigh or of ancient Britain?”

In 1925 he became director of the Rochester Museum. Under his leadership, this small museum became an institution of national significance.

During the depression, Parker organized the Seneca Arts and Crafts Project. According to its original proposal:

“The Rochester Municipal Museum proposes a project by which the almost extinct arts and crafts of New York Indians may be preserved and put on a production basis in order that such activity and products may contribute to the relief and self-support of the said Indian population.”

The Project was set up in an abandoned school and the artists set about reproducing traditional items. Illustrations and photographs from museum collections and archaeological sites were used as guidelines. As with his museum exhibits, Parker was intent on maintaining consistency with the ethnographic record.

The Project produced over five thousand separate arts and crafts items, all of which were retained as the property of the museum. The Project not only provided employment for Indians, it also raised the museum’s profile during a time of economic cutbacks and uncertain visitor numbers.

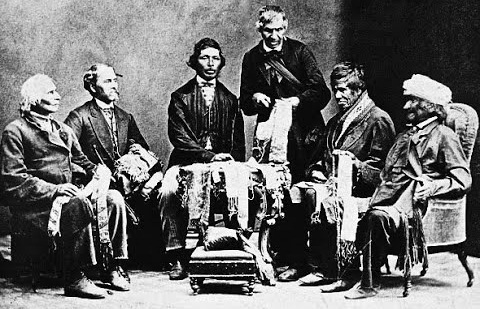

Parker was also involved with one of the earliest pan-Indian organizations in the United States. In 1911, a group of well-educated Indians-often described as “Indian intellectuals”-formed the Society of American Indians (SAI). Joining Parker to found the SAI were Dr. Charles A. Eastman (Sioux), Sherman Coolidge (Arapaho), Thomas L. Sloan (Omaha), Charles Daganett (Peoria), Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai-Apache), and Zitkala-sa (Sioux). One of the purposes of the SAI was to push for a reform of Indian policy.

At the first SAI national conference in Columbus, Ohio, one of the founders, Thomas L. Sloan, told the group:

“The evil seems to be that the Indian Bureau administers as if the Indian was selected for their benefit, to exploit them, and not they that were created for the benefit of the Indian.”

Most of the fifty Indians who came together for this first meeting were graduates of industrial or boarding schools. As a result of this first meeting, the SAI lobbied for a national Indian day and fought against the use of terms like “buck” and “squaw”. The group was dedicated to full Indian participation in American society as well as to the preservation of their racial identity. They hoped to forge a new relationship between Indians and non-Indians, incorporating what they saw as the best attributes of both worlds.

The very existence of the SAI as an organized body of Indian doctors, engineers, teachers, and professional people developed considerable respect for Native Americans.

The SAI held its second national conference in 1912 in Columbus, Ohio. One of the important issues which the group discussed was how to speed up the assimilation process on the reservations. At this meeting Parker formed two fraternities: the Loyal Order of Tecumseh and the Descendants of the American Aborigines. The Loyal Order of Tecumseh allowed both active and associate SAI members to socialize and perform ritual.

Parker was also involved in the creation and publishing of the SAI’s magazine, the Quarterly Journal. He felt that the magazine held the potential for reaching a wide audience and focusing the SAI on Indian problems. The first issue appeared in 1912. In 1916, he renamed the magazine American Indian Magazine which proclaimed itself “A JOURNAL OF RACE IDEALS Edited by Arthur C. Parker.” In the first issue he published a range of conflicting viewpoints.

In the American Indian Magazine, Parker also promoted the idea of American Indian Day on May 13. He wrote:

“Heretofore Indians have considered only tribe and reservation. To them the tribe was mankind and the tribal area the world. Today there is a growing consciousness of race existence. The Sioux is no longer a mere Sioux, or the Ojibway a mere Ojibway, the Iroquois a mere Iroquois.”

He goes on to say that the race-conscious Indian will say:

“I am not a red man only, I am an American in the truest sense, and a brother man to all human kind.”

While Indian Day school celebrations were held in three states, it was denounced in the rival Indian magazine Wassaja published by Dr. Carlos Montezuma. Montezuma called Indian Day “a farce and the worse kind of fad.”

In addition to writing archaeological monographs and editing a magazine, Arthur Caswell Parker is also remembered as the author of a number of children’s books. In 1926 his book Skunny Wundy and Other Indian Tales was published. This children’s book was a collection of Iroquois stories told in the style of the Euro-American fairy tale. In the beginning of the book, he described how he had first heard the stories at his grandfather’s fireside, from buckskin and leather-clad visitors who had traveled from the wilder parts of the reservation where the longhouse people lived.

In 1928 Rumbling Wings was published. In this book, Parker describes a secret society for older boys based on Indian lore. He followed this book in 1929 with Gustango Gold, a mystery action adventure for older boys.

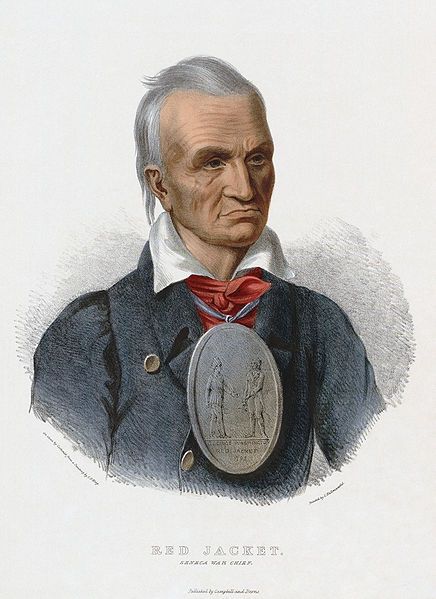

His last children’s book, Red Jacket: Last of the Senecas, was published in 1952 as a part of the McGraw-Hill biographical series.

Parker also wrote a number of books for adults. One of these was The Indian How Book (1928) which was an attempt to explain to non-Indians how Indians did things. In this book he combined healthy doses of factual information about Indians with some practical advice about surviving outdoors. The book counters some common racial stereotypes and the common notion that all Indians were nomadic hunters. Parker writes about the Iroquois Three Sisters-corn, beans, squash-and points out that the Iroquois had large fields at the time of their first contact with the French.

As modern people, Indians have belonged and participated in many non-Indian organizations. One of the most interesting of these the secret fraternal organization known as the Masons. Many prominent Indian leaders have been Masons: Cherokee leaders John Ross and Elias Boudinot; Choctaw leader Peter Pitchlyn; Creek leader Alexander McGillivray; Seneca leader Ely Parker; and Mohawk leader Joseph Brant. Brant joined the Falcon lodge in England in 1776 and had his apron presented by King George III. Like his uncle Ely Parker, Arthur Casswell Parker was also a Mason and was actively involved with Masonic life. In 1924, he was awarded the highest honor of Masonry: the thirty-third degree, an honor conferred only on a select few senior Masons.

In 1936, the Indian Council Fire of Chicago honored Arthur Caswell Parker as the “most famous person of Indian ancestry in the United States.”

Parker served as the New York State Commissioner on Indian Affairs from 1919 to 1922. In 1923 he was appointed by the Secretary of the Interior to chair the “Committee of One Hundred” to recommend changes in the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

With regard to his involvement with professional associations, Parker was the first president of the Society for American Archaeology; he founded and served as president of the New York State Archaeological Society; he served as president of the New York Historical Association; and was vice president of the American Association of Museums.

In 1954 New York, Arthur Caswell Parker organized the Nundawaga Society for History and Folklore in New York. The first pageant staged by the Society was scripted by Parker and told the story of the birth of the Seneca Nation at Nundawao and their struggle with the Massawomek (Great Snakes). The pageant was a pro-Indian history lesson. One of the obvious themes of the pageant was that the Iroquois had influenced the founders of the government of the United States.

Arthur Caswell Parker died on January 1, 1955 at his home in Seneca country at the age of 73. Men from the St. Regis Reservation conducted the traditional Seneca funeral ritual. In addition, the Masons paid their respects to their departed brother at his funeral.

At one point Parker wrote of his life:

“Nothing ever came easy for me. My obstacles have been heavy and high. I had to overcome them or perish. I chose to overcome them.”

it often surprises me how much our modern struggle for our rights is a continuation of those before us. We always called Tecumseh the first AIM leader and built our rhetoric around what he taught. And the words of Chief Seattle gave us inspiration while Chief Joeseph taught us to always persevere.

But more modern leaders like the Parkers and their contemporaries also left their imprint on our struggle. Theirs was more a rear guard struggle to preserve what was left of our societies after the ravages of centuries of genocidal policies by the invader. It’s nice to read about their lives.

What an amazing guy. Thanks so much for this history. I like that he organized people to make things for the museum and get paid.