In 1832, a war broke out in Illinois between the American settlers and the Sauk under the leadership of Black Hawk. The war lasted 15 weeks and resulted in the deaths of 70 non-Indians. While historians often call this Black Hawk’s War, it was not an invading force of Sauk warriors, but rather a migration of men, women, and children.

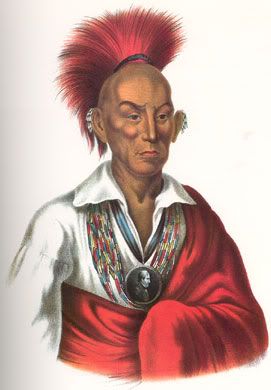

In many respects, Black Hawk was an unlikely leader. He was not a physically attractive, charismatic leader who could inspire his people with his words. He was in his sixties at the time of the war. He was a traditionalist who honored the old customs and ways, never wearing white people’s clothing or tasting alcohol in any form.

Background:

In 1828, the Indian agent told the Sauk that their village of Saukenuk had been sold and that it was time for them to move west of the Mississippi River. Mess-con-de-bay (Red Head) was adamant that the Sauk did not want to leave the bones of their ancestors. Mess-con-de-bay, a chief and a man of considerable standing, was simply dismissed by the agent as a “vile unprincipled fellow” and as a “poor trifling, mean, insignificant old man”.

In Illinois, both the Secretary of War and the state governor called for the removal of all Indians from the state. American squatters then took over a Sauk village while the Sauk were on their winter hunt. The American squatters were told that the Sauk were not going to return to the village.

Later that winter, Sauk warrior Black Hawk, concerned about rumors that the Americans had occupied their village, traveled alone through the cold, snow-filled countryside, to see for himself. He found an American family occupying his own lodge. Through an interpreter he told them to leave and not to trouble Sauk lands. The family ignored the demand.

By spring, squatters who had moved into the Sauk village turned their cattle loose into the Sauk cornfields. Black Hawk talked with the American Indian agent and was told that the Sauk should give up all notions of ever returning to Saukenuk again. The agent recommended that the Sauk establish a new village west of the Mississippi.

Disturbed by the agent’s advice, Black Hawk went to talk with Wabokieshiek, the Winnebago prophet. Wabokieshiek, who was in his mid-forties, presided over a village that was generally described as a mixture of many nations. He told Black Hawk that the Sauk should return to their village and that there should be no trouble between the Indians and the American settlers.

Sauk leader Keokuk then attempted to persuade the Sauk at Saukenuk to join the new Sauk community on the Iowa River. Black Hawk looked upon Keokuk as a traitor to his own people and refused the invitation. Black Hawk and his people attempted to live in their traditional village in a peaceful manner.

In 1830, the Indian agent for the Sauk expressed the hope that the government would provide justice for the Sauk and prevent squatters from taking over their land. The government, however, put the Sauk homelands in Illinois up for sale. When the Sauk returned from their winter hunt, they found settlers with legal titles plowing up the graves of Sauk ancestors.

In 1831, Black Hawk’s Sauk returned to their village of Saukenuk following their winter hunt. The Sauk numbered 1,200 to 1,600 people with an estimated 300 to 400 warriors. In previous years, the Sauk had returned to their village after the winter hunt in a peaceful manner. In spite of this peaceful past, the Americans responded by calling up a force of 700 militia volunteers to protect the citizens of the state from the Sauk invasion.

Once again, Black Hawk consulted with Wabokieshiek, the Winnebago prophet. The prophet told him to stay calm and peaceful. If they offered no resistance to the soldiers, the prophet told him, the soldiers would not force them to abandon their land.

The Sauk met in council with the Americans. Before General Gaines could make his opening remarks, Kinnekonnesaut jumped to his feet and spoke. Gaines became visibly irritated. He then simply read his prepared address. It seemed to the Sauk that he was unwilling, or perhaps unable, to talk with them from the heart.

Keokuk complained to the Americans that the Sioux make life difficult and dangerous for them west of the Mississippi. He also pointed out that it was too late in the season to plant crops. He suggested that the Americans allow Black Hawk’s people to remain in the village so that they could harvest the corn which they had planted.

When Black Hawk addressed the council, General Gaines demanded:

“Who is the Black Hawk that he should assume the right of dictating to his tribe? …I know him not-he is not a chief-who is he?”

Black Hawk told the general that the women owned the fields, not the men. Then a woman selected by the other women addressed the Americans. She explained that the women owned the land and that they had never sold any of it, nor had they consented to transfer any of it to the United States. Gaines dismissed her comments and said that the President did not send him to make treaties with women nor to hold council with them.

The general ordered the Sauk to move within three days. He did, however, agree to provide them with corn to replace the corn which they would be unable to harvest. Twenty-eight chiefs and warriors signed the Articles of Agreement dictated by General Haines. The Sauk were to cross the Mississippi and never return to Saukenuk.

In order to avoid any confrontation with the state militia, Black Hawk left the state, leading some of his people to Iowa. Here they found little food and starvation began.

As soon as Black Hawk left, the American militia moved into their old village of Saukenuk and burned many of the lodges. The volunteer soldiers also vandalized the Sauk cemetery.

The War:

Black Hawk led about 400 Sauk warriors and their families back into Illinois in 1832. Their goal was to reclaim their traditional village of Saukenuk. The result of this move was a series of conflicts known as the Black Hawk War. The initial response by the Governor of Illinois was to mobilize the state militia, and President Jackson was determined to crush Black Hawk. Indian agent William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) writes of the Sauk:

“a War of Extermination should be waged against them. The honor and respectability of the Government requires this: — the peace and quiet of the frontier, the lives and safety of its inhabitants demand it.”

A force of 275 American volunteers overtook Black Hawk who had only 40 warriors with him. Facing odds that seemed to spell disaster, Black Hawk sadly sent out a delegation to discuss surrender. Even though the Sauk delegation was carrying a flag of truce, the Americans opened fire. Black Hawk decided that if he was going to die, he would die fighting. Rallying his warriors, they made a suicidal attack against the larger force. They ran shouting into certain death, and then, to their surprise, the American volunteers broke and ran. In memory of the American commander, the battle became known as Stillman’s Run.

Following their victory at Stillman’s Run, Black Hawk led his warriors through the countryside, burning farmsteads and taking scalps. In Illinois, they attacked the American fort on the Apple River. Following this they battled a militia force at Kellogg’s Grove, killing five Americans.

At the oxbow lake of the Pecantonic in present-day Wisconsin, Black Hawk’s warriors battled American militia troops. The eleven Indians in the war party were defeated in a matter of minutes. Militarily this was a minor skirmish, but psychologically and symbolically it showed the Americans that the Indians could be beaten.

At Wisconsin Heights the Americans again engaged the Indians in battle. The Americans estimated that they killed 40-68 Indians, though Black Hawk later claimed that he lost only six warriors. Unknown to the Americans, some Kickapoo had joined the fight and nearly all of their warriors were killed at Wisconsin Heights.

At the Battle of Bad Axe the Sauk were finally defeated. At this battle, more than 1,300 Americans attacked the Sauk. When the Indians tried to surrender, the troops set upon them clubbing, stabbing, and shooting. It is not known how many Indians died in the massacre.

About 200 Sauk escaped from the massacre at Bad Axe by making their way across the Mississippi River where they were attacked by a Sioux war party.

Black Hawk, Wabokieshiek, Chakeepashipaho, Little Stabbing Chief, and about 25 others slipped away from the band before the beginning of the massacre. They made their way through Winnebago country and established a clandestine camp on Day-nik (Little Lake) near present-day Tomah, Wisconsin. They were discovered by the Winnebago traveler Hishoog-ka who then notified his village chief, Karayjasaip-ka, of the band’s presence. The Winnebago sent a delegation which included Chasjaka, who was Wabokieshiek’ brother, to persuade Black Hawk to end his struggle and turn himself in to the Americans. The Sauk returned to the Winnebago village where they were greeted cordially.

Black Hawk gave his medicine bag to Karayjasaip-ka. His medicine bag had been passed down from Muk-a-ta-quet, his great-great-grandfather, to Na-na-ma-kee, his great-grandfather. For Black Hawk, this medicine bag symbolized the very essence of the soul of the Sauk people.

Together with Wabokieshiek, Black Hawk set off for Prairie du Chien to turn himself in. At the Indian agent’s house, an hour before noon, on Monday August 1832, Black Hawk and Wabokieshiek appeared at the door as if they had materialized out of nowhere. Thus ended the Black Hawk War.

Aftermath:

Following his surrender at Prairie du Chien, Black Hawk, the Winnebago prophet Wabokieshiek, Sauk chief Neapope, and several others were sent to Washington, D.C. This journey would greatly enhance Black Hawk’s fame and reputation.

They had a brief meeting with President Andrew Jackson. While Black Hawk attempted to explain to the President why he had gone to war-saying that he had been driven to war by the injustices against his people-Jackson was disinterested.

The party was then sent to Fort Monroe in Virginia where they were to be imprisoned. While at Fort Monroe, there was a procession of well-known artists who painted their portraits.

After only four weeks at Fort Monroe it was decided to release the prisoners, but only after they had been taken on a tour of the United States to impress them with the immense size and power of the country. Throughout the tour of the eastern cities, the group was met by large crowds and were treated as celebrities.

In 1833, Black Hawk told his life story to government interpreter Antoine LeClaire who published it as Life of Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, or Black Hawk. The book became a best seller and went through five editions during the first year.

Leave a Reply