By 1859, the S’Klallam Indian community of Kah Tai was well established on what the American newcomers would call Port Townsend Bay in Washington. When the newcomers began to arrive they encountered Chief T’chiis-a-ma-hum who welcomed them and worked to maintain peace between the two very different groups. Since English-speaking people found Indian names difficult to pronounce, it was common for them to give Native leaders the names of European royalty. Thus the chief was called the Duke of York and his two wives were called Queen Victoria (See-Hei-Met-za) and Jenny Lind. Later historians will record the chief’s name as Chet-ze-moka, or Chetzemoka. The city park in present-day Port Townsend was dedicated to him in 1904 and in 2009 one of the new ferries between Port Townsend and Keystone was named for him.

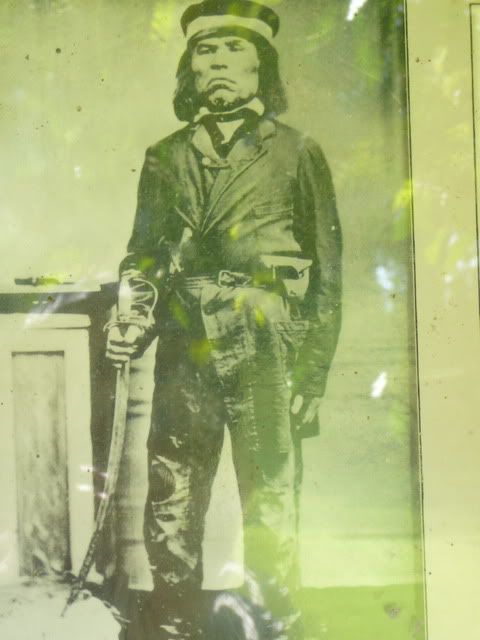

Shown above is the photograph of chief Chetzemoka which is displayed in the city park in Port Townsend which bears his name.

Chet-ze-moka was born in Kah Tai about 1808. His father, Lah-Ka-Nim, was from the Skagit tribe and his mother, Quah-Tum-A-Low, was S’Klallam. The S’Klallam are a Salish cultural and linguistic group related to other tribes of British Columbia and to most of the tribes of the Puget Sound area. S’Klallam means “strong people.”

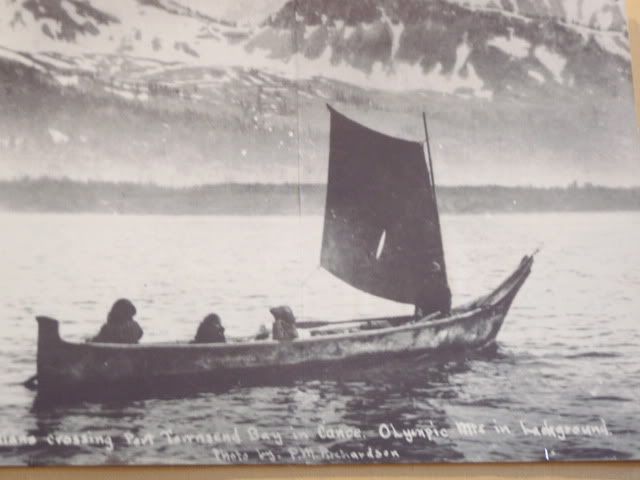

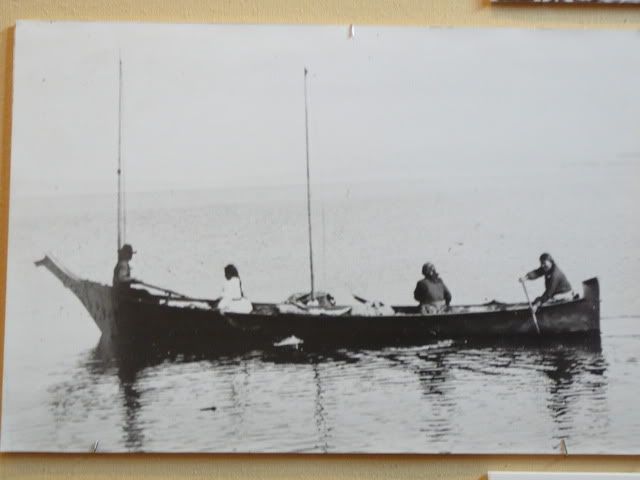

Shown above are some pictures of S’Klallam canoes. These photos are on display in the Jefferson County Museum in Port Townsend.

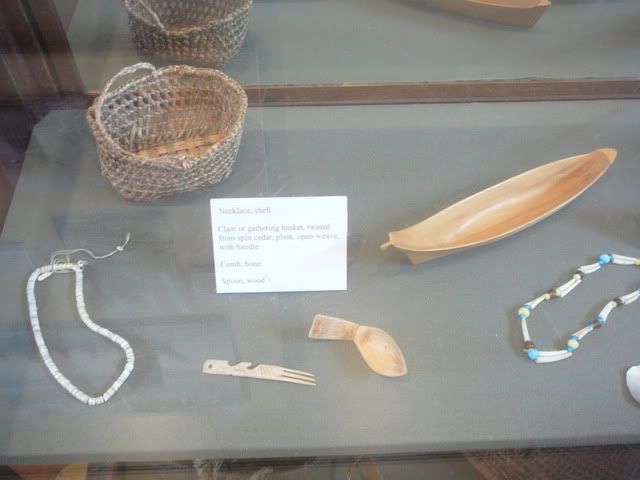

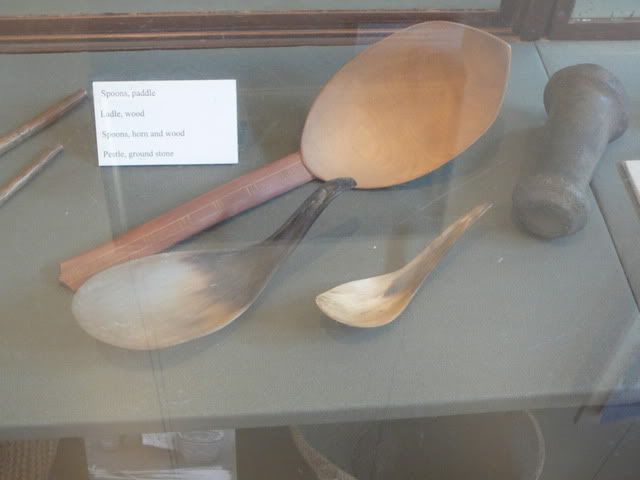

Shown above are some S’Klallam artifacts on display at the Jefferson County Museum in Port Townsend.

General A. V. Kautz visited the S’Klallam on Puget Sound in 1853. He described their housing:

“Their abodes are permanent, for they live in extensive houses, reminding me of the tobacco sheds in the east. They are formed of large posts, supporting beams, some of them so large that it is a source of wonder how they are handled.”

Traditional S’Klallam leaders basically gave advice to help settle disputes. As with most other Indian nations, chiefs could not really compel any one to do anything. Chiefs, aided by a group of advisors, made decisions regarding the utilization of fishing grounds, gathering areas, and hunting territory. Chiefs were expected to be generous. When the advisors were called upon, the chief feasted them.

When Chet-ze-moka’s brother died in 1854, Chet-ze-moka was selected chief of his people.

By the 1850s, the Indian nations in Washington were concerned about the American intrusions into their lands and arrogant disregard for tribal sovereignty and religious freedom. In 1854, a large council was held in the Snohomish village of Heb-Heb-O-Lub. Chiefs from the Nisqually, Duwamish, Skagit, Lummit, Skykomish, Snoqualme, and S’Klallam attended. Representatives from the Yakama argued for action against the American settlers. Yakama leader Owhi asked for immediate action by all of the tribes to drive the settlers out. S’Klallam chief Chet-ze-moka disagreed and suggested that peaceful coexistence was possible.

In 1854, there was an outbreak of hostilities between the S’Klallam at Dungeness and army troops. The skirmish left four dead: two S’Klallam men, an Army captain, and an Army lieutenant. Three S’Klallam men were subsequently arrested for murder and three more were flogged for a related theft. The three men who were accused of murder quickly escaped from jail. Soldiers approached a S’Klallam camp on the Hood Canal and demanded that the prisoners be surrendered. The band refused and the soldiers destroyed the camp and the Indians’ winter supply of salmon. Farther down the Canal, Chief Chet-ze-moka was captured and held hostage until the prisoners were returned.

In 1855, the S’Klallam under the leadership of Chet-ze-moka, the Skokomish under the leadership of Nah-whil-luk, and the Chimakum under the leadership of General Pierce (Kul-kah-han) met with Governer Isaac Stevens in treaty council at Point-No-Point. The tribes agreed to move to the Skokomish Reservation in Washington under the Point-No-Point Treaty. Very few S’Klallam actually moved to the reservation because it was in Twana territory, their traditional enemies.

The treaty called for the tribes to give up 438,430 acres of their ancestral land and to move to a 3,840 acre reservation within one year of ratification. The treaty also called for the tribes to stop trading at Vancouver Island, to exclude alcohol from the reservation, and to free all of their slaves (something the United States had not yet done with their African-American slaves).

One of the Americans who knew Chet-ze-moka fairly well and understood tribal feelings was James Swan. In his 1857 book The Northwest Coast; or Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory, he wrote:

“They feel as we would if a foreign people came among us, and attempted to force their customs on us whether we liked them or not. We are willing the foreigners should come, and settle, and live with us; but if they attempted to force upon us their language and religion, and make us leave our old homes and take up new ones, we would certainly rebel; and it would be by a long intercourse of years that our manners could be made to approximate.”

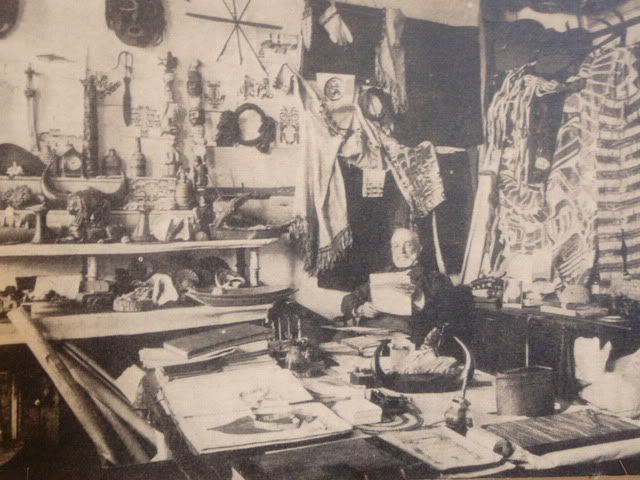

A photograph of James Swan and some of the artifacts which he collected for the Smithsonian Institution is shown above. From 1861 on, he collected and shipped hundreds of items from the Northwest Coast to the Smithsonian.

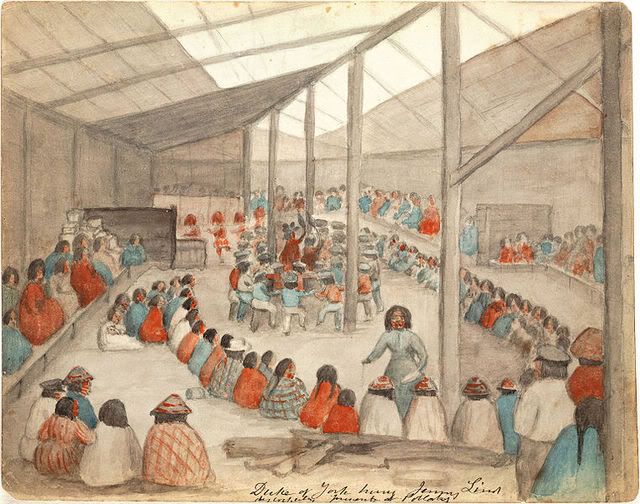

In 1859, James Swan was invited by Chet-ze-moka to observe a Chemakum tomanawos ceremony. While Swan was allowed to enter the lodge on the first night of the ceremony and to listen to the opening chants, he was not allowed to observe the rest of the ceremony even though he was Chet-ze-moka’s guest. This portion of the ceremony was closed to non-Indians. He did, however, witness the potlatch given by chief Chet-ze-moka at the end of the ceremony and sketched the distribution of presents.

Shown above is Swan’s drawing.

By 1870, the non-Indian residents of Washington were clamoring for the government to forcibly remove all Indians to reservations. In 1871, the S’Klallam at Port Townsend were ordered removed to the Skokomish Reservation. Their canoes were tied to the stern of a waiting ship. As the ship left with the S’Klallam in their canoes trailing behind, their village was burned. While the fire was deliberately set by a group of soldiers from Fort Townsend on orders from higher authorities, some official reports claimed that the fire started accidentally.

When the stern wheeler reached the Skokomish Reservation, the S’Klallam canoes were cut loose and they paddled to shore. Within a few days, most had returned to their homeland. Under the leadership of Chet-ze-moka they established a new village across the bay from Port Townsend at Indian Island.

In 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes visited Port Townsend. Among those who were introduced to the President is Chet-ze-moka (Duke of York), the leader of the S’Klallam. There is no report on the conversation between the two leaders. Chet-ze-moka was acutely aware that the treaties with the Indians of Puget Sound had not been fulfilled and most Indians at this time believed that the President had the power to order them fulfilled.

The United States government in dealing with Indians nations has always preferred to deal with tribal leaders who were absolute dictators, selected by and loyal to the United States. There has been little concern for nourishing, recognizing, or encouraging democracy among the tribes. In 1884, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs reduced the authority of S’Klallam chief Chet-ze-moka to that of a sub-chief.

Chief Chet-ze-moka died in 1888 at the age of 80. The people of Port Townsend provided an elaborate funeral. The Seattle Weekly Intelligencer reported:

“no Indian in Washington Territory, and very likely none in the United States, ever received so flattering a funeral as did the Duke of York.

”

This is very good. Do you have a bibliography?