The rest stop to the south of the interstate near Memaloose Island in Oregon has an interesting display outlining the history of the Oregon Trail.

Pathway to the “Garden of the World”

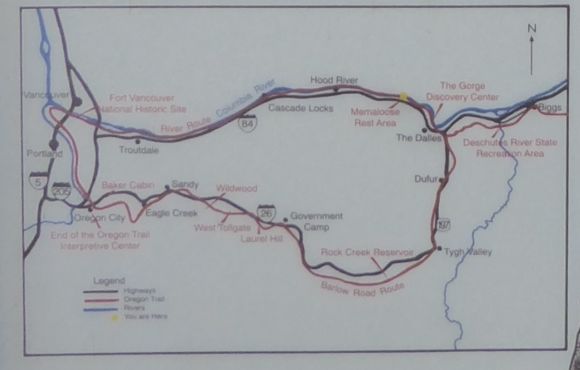

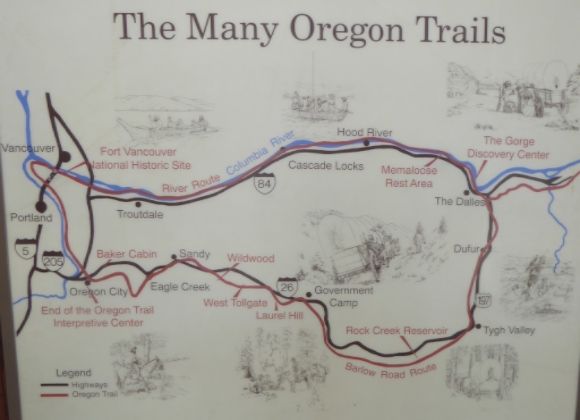

The map shown above shows the location of the Memaloose Rest Area in relation to modern highways, the rivers, and the Oregon Trails.

The map shown above shows the location of the Memaloose Rest Area in relation to modern highways, the rivers, and the Oregon Trails.

During the two decades following 1843, more than 50,000 emigrants would follow the 2,000 miles of the Oregon Trail from Missouri to Oregon. Publicists billed Oregon as a land of abundance, the Garden of the World. According to the display:

“The fragile landscape’s ability to sustain life eroded as numbers of emigrants increased, and privation, illness and death became constant companions.”

The emigrants denuded the grasslands along the trail. This had an impact on the Native peoples along the Oregon Trail. For example, when the Shoshone returned from their summer buffalo hunt, the found burned-out campfires and filthy campsites which had been left by the Americans.

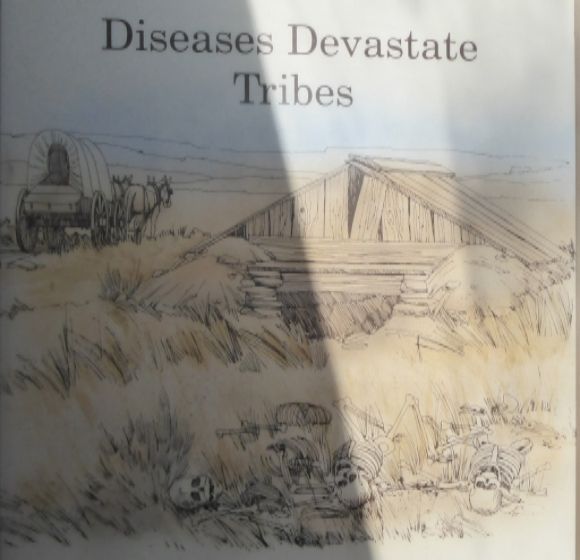

Diseases Devastate Tribes

The European-induced diseases that swept through the Willamette Valley and Columbia estuary in 1830-1832 killed about 75% of the Native American population. The impact of the disease is described by Robert Ruby and John Brown in their book The Chinook Indians: Traders of the Lower Columbia River:

“Corpses, denied canoe internment, piled up along the shores to fatten carrion eaters, and famished dogs wailed pitifully for their dead masters. Surviving natives dared not remove or care for the bodies as they normally so meticulously did.”

The disease which swept through the region at this time is described as the “cold sick.” The nature of the “cold sick” has been debated by a number of people. One explanation is that it was a type of virus influenza. Some people feel that it followed the trade routes from China. The disease is similar to epidemics which struck Europe and other parts of the globe. Others feel that it was a mosquito-carried disease such as malaria. According to anthropologist Eugene Hunn in his book Nch’i-Wána, “The Big River”: Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land:

“The requisite anopheline mosquitoes thrived along the Columbia east to near The Dalles and required only the introduction of the disease agent in the blood of an infected passenger of one of the numerous trading vessels arriving from the Mexican coast, where malaria had arrived with the African slaves brought to work colonial plantations in the sixteenth century.”

In noting the decline of Indian population in the Willamette Valley, the Reverend Gustavus Hines wrote:

“The hand of Providence is removing them to give place to a people more worthy of this beautiful and fertile country.”

Another emigrant wrote:

“This country has been populated by powerful Indian tribes, but it has pleased the Great Dispenser of human events to reduce them to mere shadows of their former greatness, thus removing the chief obstruction to the entrance of civilization, and opening a way for the introduction of Christianity where ignorance and idolatry have reigned uncontrolled for many ages.”

Indians and Emigrants

For more than 10,000 prior to the European invasion, American Indians had lived along the Columbia River and their villages occupied nearly every coast stream at numerous locations in the valleys. According to the display:

“The Indians of the Northwest perfected hunting and gathering to a fine art, and the land provided for all their needs. Oregon Trail emigrants, however, were strangers in a strange land, unable to recognize the bounty surrounding them.”

The Indian peoples along the Columbia River had a long tradition of trade and soon there was a brisk trade between the emigrants and the Indians.

Land Not for Sale

The Indians and the emigrants had very different views on the nature of the land, on how it was to be used and who controlled its use. According to the display:

“The stage was set for tragedy, especially when the federal government insisted it could buy land from a ‘head chief.’”

Since the Indian nations along the Oregon Trail did not recognize the concept of a head chief, the United States, preferring to deal with dictatorships rather than democracies, simply appointed head chiefs and then paid them to sign the treaties ceding tribal lands to the American government.

The Many Oregon Trails

According to the display:

“The Oregon Trail was never a single set of parallel wagon ruts leading from Missouri to the Willamette Valley, not did it every consist of a single route. This face was never more evident than here at Memaloose.”

Early emigrants used the river as a highway, and portaged around the waterfalls. By 1846 Samuel K. Barlow had constructed a road across the south flank of Mt. Hood which offered an alternative route to the Willamette Valley.

Emigrant Diaries

There are more than 2,000 person journals describing the Oregon Trail. According to the display:

“These diaries reflect both the personalities and varied backgrounds of their authors—determined, strong-willed individuals who gave up everything to start anew in the wilderness. Although some diarists were more eloquent than others, all recorded powerful accounts of the Oregon Trail.”

Ethnic Diversity

According to the display:

“Oregon Trail emigrants were by and large substantial citizens. Roughly $800 to $1,200 was required to obtain a proper outfit and to provide food and clothing for an entire year before crops could be planted and harvested in Oregon—this was an appreciable sum at a time when Pennsylvania coal minders were earning 44¢ per day.”

For less affluent people, the only way to make the trip was to sign on as teamsters, cattle drivers, hunters, or guides. According to the display:

“The United States was an ethnically diverse during the emigration era as it is today, and cultures from around the world were well represented on the Oregon Trail.”

Evolving Trail

According to the display:

“Westward emigration on the Oregon Trail was an annual even and every year the trail experience was unique.”

The earliest emigrants had to blaze trails, establish routes through passes, and live off the land. Later emigrants found a well-worn path to Oregon and by the 1850s many found little grass for their oxen as the oxen and horses of the earlier emigrant trains had consumed it. This meant that many were forced to lighten their loads. Beds, stoves, tables, chairs, and dishes had to be abandoned beside the trail.

Emigration peaked in 1850 when 10,000 people came overland to Oregon. In some instances, the wagons leaving St. Joseph, Missouri were twelve abreast.

Epidemic!

According to the display:

“Hardship was the common fare and not every emigrant survived. Although accidents were common, disease was a major cause of death, especially during peak emigration years when poor sanitation and contaminated water lead to epidemics of fever, cholera, and dysentery.”

Fur Trade and the Oregon Country

International fur trade which tied the Indian peoples along the Columbia River to the international markets in Europe and Asia began in 1778 when Captain James Cook and his crew began to bargain with Indians for sea otter skins. In 1811, John Jacob Astor’s fur trading empire established a small trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River (this would become Astoria). By 1812, the Astorians were coming overland and what would become the Oregon Trail.

The Oregon Question

According to the display:

“In 1818 Great Britain and the United States agreed by convention that their citizens could engage in commerce in the Oregon country without prejudice to either nation’s claims.”

By the 1840s, the United States was prepared to go to war with Britain to claim exclusive title to the territory. In 1846, three years ago the large American emigration to Oregon began, the 49th parallel was established as the northern boundary of the United States. Indian nations were not consulted about the new boundary. International law recognized that Indian nations held title to their land, but sovereignty was granted to the Christian European nations — England and the United States, in this case — because of the “right of discovery.”

Oregon Fever

According to the display:

“Westward emigration was motivated by more than politics and clever slogans: some people sought relief from a depressed economy; some were evading the law; others were simply nomads in search of new horizons.”

Leave a Reply