Yankton Sioux (Nakota) writer and activist Gertrude Simmons Bonnin was born in 1876 and grew up on the Yankton Agency in South Dakota. Her mother was Reaches for the Wind (Tate I Yohin Win, also known as Ellen). Her father abandoned his wife and Ellen married John Haysting Simmons. Gertrude Simmons grew up on the Yankton Agency listening to the traditional Nakota stories.

In 1884, she left the reservation to study at White’s Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana. In his biography of Gertrude Bonnin in Notable Native Americans, Ron Welburn writes:

“This development began a lifelong struggle between traditional ways and progressive endeavors.”

Her mother, Ellen Simmons, distrusted the missionaries’ efforts to educate Indian children.

In 1888, Gertrude went to Nebraska to study at the Santee Normal Training School and in 1895 she went to Earlham College in Indiana. Ron Welburn reports:

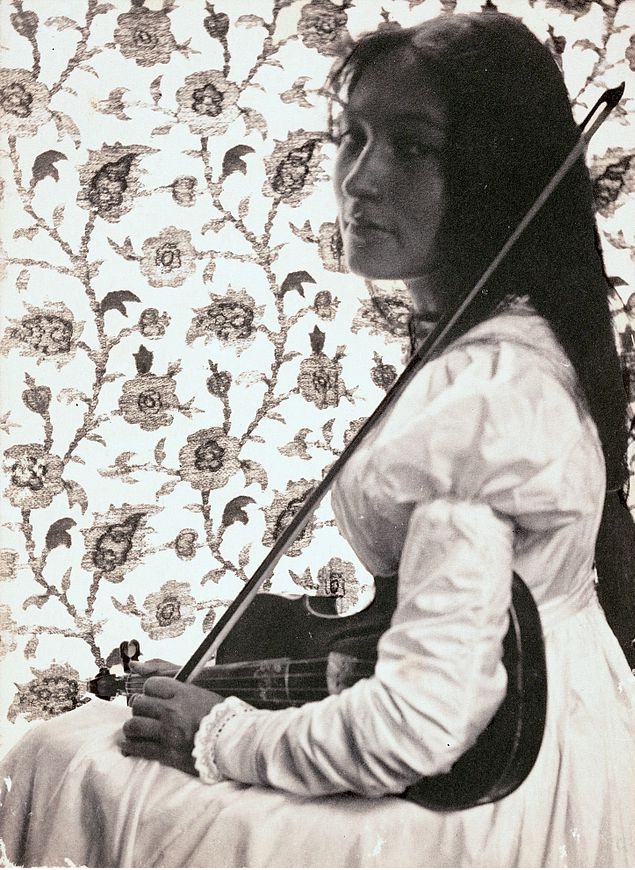

“She lived in a social milieu of Christian acculturation, which she bravely maintained in balance with her traditional upbringing and knowledge. At Earlham she applied herself vigorously to studying music, becoming a respectable violinist.”

Her interest in studying music took her briefly to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. By the end of the century, she was teaching at the Carlisle Indian School and performing in its orchestra.

Unlike Henry Pratt, the founder of the Carlisle Indian School, and other non-Indian educators, she disagreed with the notion that Indians should only be taught skills related to farming and domestic work (i.e. training to become servants): she felt that Indian children should be taught all academic subjects, including those unrelated to jobs requiring manual labor.

In 1900, she went to Paris, France, where she performed as a solo violinist at the Paris Exposition.

Under the name Zitkala-Sa (Red Bird), she published short stories in Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s Monthly. In 1901, she published a collection of short stories entitled Old Indian Legends.

In 1901, her friendship with Dr. Carlos Montezuma, a Yavapai Indian from Arizona who had graduated from the Chicago Medical College, blossomed into romance and the two became engaged. Ron Welburn writes:

“Both were strong-willed individuals and although they broke off the engagement that summer, they continued corresponding—sometimes with fierce debate—for decades.”

In his book Carlos Montezuma and the Changing World of American Indians, Peter Iverson writes:

“Her engagement to Montezuma ended unhappily. The proud Yavapai physician did not like being spurned, and, to make matters worse, Zitkala-Sa lost the engagement ring he had sent her.”

In 1902, she married Captain Raymond Bonnin, a Nakota who worked for the Indian Bureau. Their son Raymond Ohiya Bonnin was born in 1903.

In 1913, she collaborated with William Hanson, a classical music composer, to create an opera, Sun Dance. The work premiered in Vernal, Utah and in neighboring states. For two decades the opera lay dormant and then,in 1937, it was selected by the New York Light Opera Guide as their American opera of the year. Ron Welburn writes

“Operas about American folk life gained popularity during the twenties and thirties, yet none about Native Americans except this one were co-authored by a Native American.”

The Bonnins moved to Washington, D.C. in 1916 where Gertrude was involved with the Society of American Indians (SAI), an organization which had been founded in 1911. Regarding the SAI, Joy Porter, in her book To be Indian: The Biography of Iroquois-Seneca Arthur Caswell Parker, reports:

“It voiced Indian demands for reform, defined Indian responsibility for change, and articulated the conditions it alone considered necessary for full Indian integration.”

In his book Black Hills/White Justice, Edward Lazarus writes:

“Dedicated to full Indian participation in American society as well as to the preservation of their racial identity, “the Indians of the SAI hoped to forge a new relationship between white and red America, incorporating what they saw as the best attributes of both cultures.”

In 1916, the first issue of American Indian Magazine appeared with the slogan “A Journal of Race Ideals.” The new magazine was edited by Arthur Caswell Parker (Seneca). The first issue included a wide range of views, including those of Yavapai physician Dr. Carlos Montezuma, one of the founders of the Society of American Indians. Gertrude Bonnin’s poem “The Indian’s Awakening” was also published in the premier edition.

At the 1916 meeting of the Society of American Indians in Cedar, Rapids, Iowa, Gertrude Bonnin was elected secretary. She was also active in non-Indian organizations including the League of American Pen Women and the General Federation of Women’s Clubs.

In 1918, a bill was introduced in Congress which would outlaw the use of peyote by Indians. Gertrude Bonnin, the Society of American Indians, the Carlisle Indian School, and the Indian Office all supported the bill. The bill was passed by the House but was rejected by the Senate. In 1920, Gertrude Bonnin resigned from the Society of American Indians because of conflicts with the leadership of Thomas Sloan (Omaha) who defended the use of peyote. The Society of American Indians folded in 1923.

In 1921, her book American Indian Stories was published. Her essay “Why I Am a Pagan” was retitled as “The Great Spirit” and was edited to remove some material. In her University of Montana M.A. thesis Zitkala-Sa: The Native Voice from Exile, Dorothea Susag reports:

“With these changes, the final tone of the essay changed from anger to reassuring peace.”

During the first part of the twentieth century oil and natural gas resources had become increasingly valuable and in Oklahoma it was not uncommon for these resources to be found on Indian land. Motivated by greed and enabled by governmental corruption and racism, non-Indians sought to make sure that Indians could not become wealthy because of these resources. The county courts appointed guardians to manage Indian estates and these guardians charged high fees for their services and attempted to lease oil and gas rights to their friends at low prices. As a result, most Indians stayed poor and wealthy Oklahomans increased their wealth. In addition, the government limited the amount of money an Indian could spend and had to approve their purchases.

In 1924, Gertrude Bonnin of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs and the Indian Welfare Committee and Charles Fabens, attorney for the American Indian Defense Association, wrote Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes—Legalized Robbery. This work, according to historian Tanis Thorne, in his biography The World’s Richest Indian: The Scandal Over Jackson Barnett’s Oil Fortune:

“…was a particularly powerful political weapon because it gave the statistical evidence of corruption and attendant Indian suffering a human face.”

Among other things, they reported that administrative fees ranged from 20 percent to 70 percent.

In 1924, more than 400 Indians gathered in Tulsa to form a state-wide protective association—the Oklahoma Society of Indians—which could fight against further exploitation. Copies of Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians were distributed to those in attendance.

The National Council of American Indians was formed in 1926 to induce Indians to participate in national politics. The organization’s slogan was “Help the Indians Help Themselves in Protecting Their Rights and Properties.” Gertrude Bonnin was the group’s founder and first president.

Gertrude Bonnin died in 1938 in Washington, D.C. The National Council of American Indians was dissolved soon after her death.

Leave a Reply