A treaty is simply an agreement between two or more sovereign nations. Following the Constitution, the United States recognized Indian nations as sovereign entities and thus negotiated treaties with them. In negotiating treaties with Indian nations, the Americans viewed the treaties, and the Indians themselves, as being temporary. Convinced that Indians were destined to vanish, the Americans generally viewed treaties as a way of increasing the pace of assimilation and the destruction of Indian cultures. In addition, since Indians were viewed as a vanishing people, treaties were seen as temporary.

While it is common to talk about Indian treaties as “peace” treaties, it is a misconception to assume that Indian treaties came about through warfare. While nearly all Indian treaties contain a clause or section about peaceful relationships between the United States and the Indian tribes, and between those tribes friendly to the United States, Indian treaties for the most part were never the end product of a war in which Indian nations were militarily defeated.

In addition to establishing peace, and thus preventing war, the United States negotiated treaties to obtain land. The United States frequently gave voice to the idea that no Indian land was to be taken without the consent of the Indians. At the same time, the United States had a policy of recognizing Indian leaders who were favorable to land cession and who were willing to accept bribes.

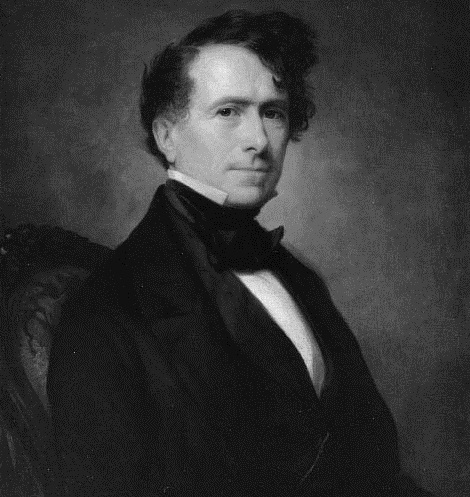

In 1853, President Franklin Pierce appointed Isaac I. Stevens as governor of Washington Territory (which included present-day Washington, Idaho, and Western Montana). As governor, Stevens was also the superintendent of the territory’s Indian affairs even though he had no previous experience with American Indians. Stevens, a graduate of West Point, had been an engineering officer in the army and had served on General Winfield Scott’s staff during the Mexican War of 1846-1847. Like many others in the American government at this time, he viewed Indians as racially inferior and as impediments to the expansion of American civilization. In their book Renegade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, Clifford Trafzer and Richard Scheuerman write:

“Stevens believed himself to be superior, and he assumed from the outset that whites had a right to direct Indian policy, thus determining their future—regardless of what the Indians thought.”

In 1853, Congress authorized commissions to purchase lands from the northwest tribes and to remove the Indians from these lands. The Act envisioned a removal similar to that of the southeastern tribes in which the Indians would be given lands not wanted by American settlers.

In 1854, Stevens set out to negotiate treaties with the Indian nations in Washington Territory. Stevens was a firm believer in Manifest Destiny. He wanted to establish firm boundaries for tribal territories, to put Indians on reservations, and to clear the way for the planned Northern Pacific Railroad. Anthropologist Clifford Trafzer, in his preface to Indians, Superintendents, and Councils: Northwestern Indian Policy, 1850-1855, describes Stevens this way:

“An ardent advocate of white expansion, Stevens wanted to liquidate Indian title to the land and concentrate as many Indians as possible on a few reservations.”

Historian Roberta Ulrich, in her book Empty Nets: Indians, Dams, and the Columbia River, writes:

“His major mission was to compress the Indians onto as little land as possible, preferably in areas not coveted by whites, to open the way for settlement.”

According to Clifford Trafzer and Richard Scheuerman:

“Since his principal concern was the opening of Indian lands for the expansion of the American empire, Stevens devoted himself to extinguishing Indian title to the land.”

Regarding the Stevens treaties, Alexandra Harmon, in an article in Oregon Historical Quarterly, writes:

“Governor Stevens and his colleagues resolved to streamline the treaty-making process and minimize the federal government’s subsequent administrative burden by sorting the Indians into a few large groups, which they called tribes.”

To facilitate the treaty process and to develop the treaty language, Governor Stevens appointed a formal territorial commission. One of the members of the commission, Frank Shaw, would later write:

“Personally, I have always believed that there was a great deal of humbug about making treaties with Indians…The question was, shall a great country with many resources be turned over to a few Indians to roam over and make a precarious living on, making no use of the soil for timber or other resources, or should it be turned over to the civilized man who could develop it in every direction and make it the abiding place of millions of white people instead of a few hundred Indians.”

With regard to the American rationale, Richard Kluger, in his book The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek: A Tragic Clash Between White and Native America, writes:

“The Americans were on the side of morality and compassion because, according to their government’s official rationale, the natives were being liberated from their savagery by being separated from their land.”

From the government’s perspective, the Stevens treaties were seen as a way of obtaining large tracts of land which would be secure for the settlers. Historian Kent Richards, in his biography of Stevens in Shadows of Our Ancestors: Readings in the History of Klallam-White Relations, writes:

“In conducting the treaty sessions, he did not think it necessary to pay much heed to Indian complaints that traditional customs, habits, superstitions, or religious mores would be violated by the treaties. After all, the long-term consequence of the treaties, in Stevens’ view, was to replace the traditional pattern of Indian life with the superior white civilization.”

In general, the Stevens treaties called for the tribes being restricted to certain areas (reservations) and it was not uncommon for tribes with totally different languages and cultures to be grouped together.

In his book The Indian Frontier of the American West 1846-1890, historian Robert Utley writes of Stevens’ negotiating tactics:

“His methods featured fast talk, bluster, and intimidation, and when he finished he had stampeded virtually all the groups of the territory into signing treaties.”

One of the practices used by Stevens was to create both chiefs and tribes who would sign the treaties that he dictated to them. In addition, Stevens would group unrelated tribes together under a single leader whom he had designated.

Coastal Treaties

Prior to the Stevens Treaties and the reservation system, there were more than 50 distinct, named, and autonomous tribal groups in this area. Each of these groups had one or more winter villages, several summer camps, and a recognized resource area. There was no overall political structure which united them.

In Western Washington, Stevens wanted to create only a few reservations for the Indians and to move them from their historic homelands to these reservations.

In anticipation of negotiating treaties with the Indians of the Puget Sound area, Governor Isaac Stevens appointed Michael Simmons as special agent to visit all of the Indian camps and villages. Simmons was to compile statistics on the groups so that they could be consolidated into tribes and placed on reservations. He was also to appoint tribal leaders with whom the governor was to negotiate the treaties.

In the treaty councils, Stevens attempted to impose on all of the Indian nations the same boiler-plated treaty. Clifford Trafzer and Richard Scheuerman, in their book Renegade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, report:

“By and large the coastal treaties were nearly identical, each calling for the end of tribal warfare, the surrender of the Indian lands, and the establishment of reservations.”

In addition, the treaties recognized the Indian right to hunt and fish at all usual and accustomed places. There were also promises of schools and medical care.

Stevens insisted that treaty negotiations be conducted in Chinook Jargon. As a jargon or trade language, Chinook Jargon has a limited vocabular which centers on trade. This means that many of the legal complexities involved in the treaties were lost in translation as Chinook Jargon had neither the vocabulary nor the syntactic structures to deal with these concepts.

Governor Isaac Stevens met with the coastal Indian nations in treaty councils at Medicine Creek, Point Elliot, Point-No-Point, Neah Bay, Grays Harbor, and Quinault River. Stevens did not explain to the Indians that, from the American viewpoint, the reservations established by the treaties were to be temporary.

Eastern Washington Treaties

The Columbia Plateau is the area between the Cascade Mountains and the Rocky Mountains. This is an area which has historic ties with and similarities to both the Northwest Coast and the Plains. The Indian nations in this area had both linguistic and cultural diversity.

In 1854, Governor Isaac Stevens met with Yakama leader Owhi to discuss a treaty council for the coming year. Owhi told Stevens that the Yakama were not interested in selling their land and that they wanted to be left alone by the Americans. Stevens responded by telling Owhi that if the Yakama did not sell their land, then the Americans would simply take it by force and wipe them off the face of the land.

Owhi repeated Stevens’ words to Kamiakin. Kamiakin asked Owhi to send for Quiltenenoc and Moses so that they could hold a council. Kamiakin also sent word of the council to the Nez Perce war chief Looking Glass.

Kamiakin discussed Stevens’ remarks with the Oblate Catholic fathers and was told by the priest:

“The whites will take your country as they have taken other countries from the Indians.”

After hearing these gloomy words, Kamiakin and his brother Skloom traveled to Peo-peo-mox-mox’s village. Here Kamiakin unveiled a plan for an Indian confederacy of all the tribes in the region to resist American occupancy of their lands.

In 1855, the Americans met with the Eastern Washington tribes at a site near present-day Walla Walla. Governor Stevens planned to establish two reservations: one in Nez Perce country for the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Spokan, and one in Yakama country for the Yakama, Palouse, Klikatat, Wenatchee, Okanagan, and Colville. In his chapter in As Days Go By: Our History, Our Land, and Our People—The Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla, Antone Minthorn reports:

“All the tribes attending the Treaty Council understood that the U.S. government was forcing the Indians to choose a place for a reservation to prevent war and to stay out of the way of the settlers rushing in to make claims on their land.”

According to the Nez Perce Tribe, in their book Treaties: Nez Perce Perspectives:

“Stevens intentionally neglected to tell the Indians that he had specifically selected lands for their reservations that no white man yet wanted, and, perhaps most importantly, he made no mention of his desire to secure land for the railroad.”

According to historian Alvin Josephy, in his chapter on the Walla Walla council in The Western American Indian: Case Studies in Tribal History:

“The transparency of the speeches of Governor Stevens and Superintendent Palmer is so obvious that it is a wonder the commissioners could not realize the ease with which the Indians saw through what they were saying. One can only assume either that their ignorance of the Indians’ mentality was appalling or that they were so intent on having their way with the tribes that they blinded themselves to the flagrancy of their hypocrisy.”

Stevens made many grand promises to the Indians during the treaty negotiations, most of which were not included in the actual treaties. Twelve days after the treaties were signed at Walla Walla, the newspapers in Washington and Oregon announced that the land east of the Cascade Mountains was now open for American settlement. The announcement, made with the approval of Governor Stevens, ignored the fact that the treaties had to be ratified by the Senate and proclaimed by the President before they were legally binding and that the Indians had been promised that there would be no American settlement for two or three years.

Montana Treaties

In 1855, Governor Stevens journeyed to Western Montana and imposed treaties on the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai, all tribes he considered to be unimportant. His goal was to create a small reservation which would serve as the home to these tribes and others and which would then free up land to allow the railroad to come through. The Treaty of Hell Gate established the Flathead Reservation in Montana for the Flathead (also called Salish), Pend d’Oreilles (also called Upper Kalispel), and Kootenai.

Stevens then travelled east of the Rocky Mountains to Fort Benton, outside of Washington Territory. Here the Stevens party met with chief trader Alexander Culbertson who convinced them to hold the treaty council with the Blackfoot at the mouth of the Judith River. The Treaty of Judith River (also known as the Lame Bull Treaty) with the Blackfoot established the Great Blackfeet Reservation which included 17.5 million acres north of the Missouri River and east of the Rocky Mountains. The treaty promised to provide the Blackfoot with annuities, to provide them with instruction in agricultural pursuits, to educate their children, and to promote their civilization and Christianization. In summarizing the treaty, Charles Forbes, in his University of Oklahoma Master of Arts thesis, writes:

“The treaty was a step in the transitional process by which the United States intended in a decade to produce a nation of farmers, abiding by laws developed from a code of England, and devoted to a religion started at Jerusalem. The customs, religion and mode of living that had been developed through the centuries by the Blackfeet to fit their needs were disregarded.”

Leave a Reply