When the European explorers, soldiers, missionaries, and colonists arrived in the Americas, they viewed the world through the lens of Christianity. Encountering peoples who were not mentioned in the Bible, there were great debates about who these people were and, if they were truly human, how they travelled from the mythical Garden of Eden, which Christians believed to be in Mesopotamia, to the Americas. There were some who believed that American Indians were sub-human, an animal-like people without souls; there were others who claimed that Indians were Jews, one of the Lost Tribes of Israel; still others saw American Indians as atheists, Satanists, people who had rejected the Christian god and who were therefore a condemned people.

The United States came into existence in the late eighteenth century and among its foundational myths was the view that Indians were savage, primitive, and nomadic, whose subsistence depended on hunting. Since the Americans viewed Indians as incapable of developing the land, this viewpoint enabled them to justify in their own minds taking lands which the Indians had farmed for centuries, ignoring the facts that Indians were not nomadic hunters but lived in permanent villages. The worldview of Indians as primitive nomads was challenged as American colonists encountered the great earthworks, pyramids, and burial mounds, which are found along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. While it should have been obvious that these structures had been built by American Indians, Kenneth Feder, in article in American Archaeology, reports:

“…many Americans of European descent refused to believe that America’s aboriginal inhabitants possessed such capabilities. Consequently, it was thought that some other group was responsible.”

During the nineteenth century, many fanciful ideas about “the other group” were put forth. In his 1930 book The Mound-Builders, Henry Clyde Shetrone summarizes some of the nineteenth-century ideas:

“From the ancient Chinese, Phoenicians, and Egyptians at one end to the Welsh and the Irish at the other is but a suggestion of the range of supposed sources of origin. The Ten Lost Tribes of Israel seem to have been an alluring subject of consideration for those who saw an opportunity of clearing up two major mysteries in the simplest possible manner.”

In was in this milieu in 1830, that a new religious book, The Book of Mormon, was published and, unlike the Bible, explained American Indian history. In an article in The Indian Historian, John Price reports:

“It was written by an amateur archaeologist from rural northwest New York who had dug in the local Indian burial mounds. The book appears to be constructed from theories that were popular in the author’s day: the America’s were settled by lost tribes of Israel, the Moundbuilders had been more civilized than the local Iroquois, the Moundbuilders were destroyed in a great war in which the ancestors of the Iroquois were victorious, and Von Humboldt’s claims of finding the remains of a lost civilization in Central America were true.”

According to Joseph Smith an angel had led him to a hillside near Manchester, New York, and showed him golden plates engraved with strange characters. After months of concentrated work using a special instrument, he was able to translate the plates and published hundreds of pages of history, prophecy, and poetry that provided the foundation for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (the Mormons).

The book claims that the ancestors of American Indians are the Lamanites, ungodly savages who were punished by God by turning their skins dark. Indians, according to the Book of Mormon, are descendants of Israelites who came to the Americas about 600 BCE. Shortly after their arrival, they divided into two great civilizations, one which followed the true gospel and the other which followed darkness and apostasy.

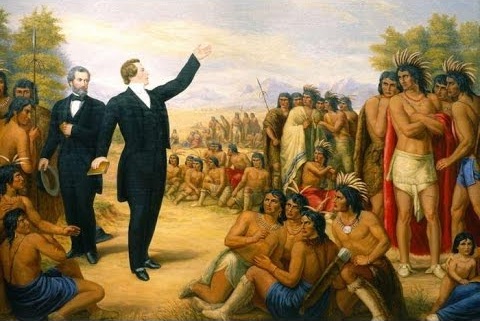

The Book of Mormon describes how Jesus came to the Americas following his resurrection and preached to the American Indians. According to William Brandon, in his book Indians:

“The Book of Mormon, stating that the Indians were descendants of the tribe of Joseph, one of Israel’s twelve tribes, dubbed them Lamanites, and offered a history for their movements from 600 B.C. until the Resurrection, when Christ appeared to them here and there under the guise of Viacocha, Kukulcan, or Quetzalcoatl.”

In his book Termination’s Legacy: The Discarded Indians of Utah, historian Warren Metcalf writes:

“In Book of Mormon cosmology, contemporary American Indians are the fallen and degraded descendants of these enlightened ancient Americans; a corollary doctrine holds that Mormons have a duty to elevate American Indians to their former status as members of God’s kingdom on earth.”

Joseph Smith announced that he had received a revelation to carry the message of the Book of Mormon to the Indians. In her book American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857, Sally Denton reports:

“The Mormon sect’s essential doctrine, deeply rooted in the story of how the wicked Lamanites defeated their white relatives and went on to become the American Indians, stipulated as a condition and precursor of Christ’s return to earth that the Lamanites would rejoin the faith.”

Sally Denton also writes:

“[Smith] dispatched his apostles to the west to find a site upon which to build the New Jerusalem and to persuade the Indians, whom Smith’s followers now called Lamanites, that the Book of Mormon was the history of their ancestors. The natives proved reluctant converts, and the proselytizing effort was a colossal failure.”

In his book Utah, the Right Place: The Official Centennial History, Thomas Alexander writes:

“The attitude of the Latter-day Saints toward the Indians represented a convergence of theology, Euro-American imperialism, and racism.”

The Book of Mormon teaches that Indians had descended from Israelite peoples who had migrated to the American continent prior to the Babylonian captivity. Thus, the Mormons viewed Indians as Children of Israel who could be incorporated into God’s Latter-day Kingdom. In his chapter in A History of Utah’s American Indians, Robert McPherson writes:

“From a purely ideological point of view, the Mormons believed that the Indians were a remnant of a people who fell out of grace with God, were given a dark skin as a sign of their spiritual standing, and who now lived in an unfortunate condition awaiting restoration to an enlightened state.”

The first Mormon settlers arrived in Utah in 1847 and they were soon followed by a stream of Latter-day Saints seeking the promised land. Following the European settlement pattern, they sought to support themselves through agriculture. The Gosiute tribe showed them some of the wild edible plants, such as the sego lily root, as a way of surviving until their crops could be harvested.

In their chapter in A History of Utah’s American Indians, Gary Tom and Ronald Holt write:

“Mormon theology came as a two-edged sword for the Paiutes. According to Book of Mormon teachings, Indians were seen both as a chosen people and as a cursed people.”

In order to be saved, the Indians first had to be “civilized” which meant that they had to assimilate. Gary Tom and Ronald Holt also report:

“One of the major points of contention with the Mormons was that the Paiutes and other tribes should not worship symbols such as the sun, stars, and moon.”

Mormon men who were called or appointed as missionaries learned the Indian languages, worked with the tribes, and then attempted to lead them into the fold of Christ’s church. Robert McPherson writes:

“What happened in practice was often at odds with this and was often met by cultural and armed resistance.”

Thomas Alexander writes:

“Although Mormon theology supported the efforts at conversion, Euro-American attitudes influenced decisively the practical dealings with the Native Americans.”

With regard to the land, the Mormons, like other Europeans, disregarded Indian title to the land. Thomas Alexander writes:

“The land, they said, belonged to the Lord. Only the priesthood could apportion it, and then only on principles of stewardship.”

Gary Tom and Ronald Holt write:

“Justification for taking the land was given by the Mormon church and its members, including the idea that the Indians were not making efficient use of the land and therefore the Mormons had the right to take it over because they could support more people by their methods of agriculture than the Indians could.”

The Mormon expansion was fairly rapid, driven by the need to acquire land for converts. The new Mormon settlements took the best farmlands and the best water sources. Indians were often employed to help prepare the fields and for various household chores.

With regard to the conversion of Indians to Mormonism, many people believed—and some still believe—that the darker skin color of Indians had been caused by their rejection of the Christian god and that through conversion, their skin would become lighter in color.

Indians 101/201

Indians 101/201 is a series exploring American Indian histories, cultures, biographies, museums, and current concerns. Indians 201 is an expansion of an earlier essay.

I wondered about Mormon theology and Ameican Indians, thank you for the information. Now I know where people are coming from when they say certain things.