By 1776, some of the British colonists in North America had become somewhat irritated with the Monarchy and particularly with its limitations on the expansion of the colonies. Colonial displeasure with the British King was expressed in a document known as the Declaration of Independence in which they express the following charge against the King:

“He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.”

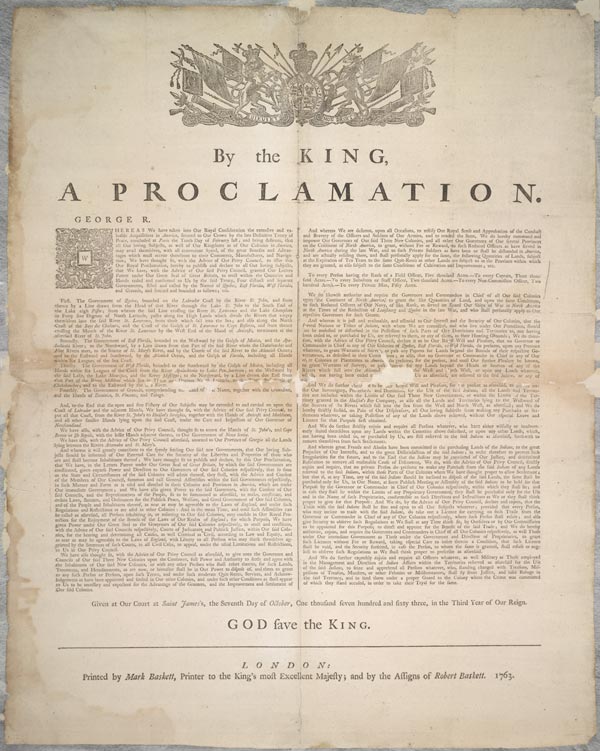

The last portion of this charge—“ raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands”—is a reference to the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris officially ended the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War). Under the terms of the treaty, which was negotiated with no Indian leaders present, all of the Indian nations east of the Mississippi River were to come under the jurisdiction of the English. According to John Tebbel and Keith Jennison, in their book The American Indian Wars:

“The end of hostilities between France and England left the Indian population east of the Mississippi in a sullen, embittered mood. They felt themselves used and unfairly rewarded for what little they had done to make the British victory possible.”

Under the Treaty of Paris, the British acquired Canada and Illinois. The Spanish acquired all of the French holdings west of the Mississippi River.

In the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the English King drew a boundary line from Nova Scotia to Florida following the Appalachians which was intended to separate the Indians from the colonists. Under this decree, non-Indian settlement of the west was prohibited and squatters currently living in the area were to be removed. With this decree, only the Crown had the right to obtain land from Indians. Historian Frances Jennings, in his book The Creation of America: Through Revolution to Empire, reports:

“Thus by royal prerogative alone, a vast territory was reserved temporarily as Indian hunting grounds, colonials were forbidden to settle west of a line on the map while colonial charters were arbitrarily curtailed at that line, and new colonies were decreed in East and West Florida and Province of Quebec.”

In his book In the Courts of the Conqueror: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided, Walter Echo-Hawk reports:

“This decree prohibited the settlement of any Indian land west of the Allegheny Mountains, ordered squatters to leave, and authorized only the Crown to acquire Indian lands. Thus, beginning in 1763, Indian land could only be purchased by colonial governments in the name of the Crown.”

The Proclamation also assumed imperial authority over the Indians, thus claiming the continent while allowing Indians to live upon it at their grace and favor. Historian Donald Smith, in his book Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians, writes:

“The Royal Proclamation of 1763 had become the Magna Carta of Indian rights in British North America, immediately prohibiting the purchase of Indian lands by private individuals.”

Anthropologist Charles Hudson, in his book The Southeastern Indians, writes:

“The British never had the wherewithal to enforce the boundary, and neither the colonists nor Indians took it seriously.”

Many of the European colonists, such as George Washington, simply viewed the proclamation as a temporary expedient to calm the Indians. Regarding George Washington, historian Joseph Ellis, in his book His Excellency: George Washington, writes:

“He regarded the Indian tribes of the region as a series of holding companies destined to be displaced as the growing wave of white settlers flowed over the Alleghenies.”

In his book In the Courts of the Conqueror: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided, Walter Echo-Hawk writes:

“For George Washington, black-market buying was simply a good investment opportunity.”

Washington bought as much land as possible west of the demarcation line. Washington wrote:

“Any person therefore who neglects the present opportunity of hunting out good Lands and in some measure marking and distinguishing them for their own (in order to keep other from settling them) will never regret it.”

European settlers simply ignored the new line and continued to settle on Indian land, to build blockhouses, and to dare the Indians to force them out. In his book Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous Peoples of Their Lands, Lindsay Robertson writes:

“Most colonists loudly protested the proclamation, viewing it as an unconstitutional denial of access to lands they had fairly won by defeating the French in the Seven Years’ War.”

In the end, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was simply one more grievance against the British monarch for not recognizing that American Indians should have no rights, and particularly no land rights, that would be equal to those of the colonists. For the colonists, the First Nations of North America should have no property rights as they were too warlike and savage.

In 1768, the British Crown rescinded the Proclamation of 1763 and gave control over Indian affairs back to the colonies.

Indians 101/201

Indians 101/201 is a series exploring American Indians histories, arts, biographies, and current concerns. Indians 201 is an expansion and revision of an earlier essay. More from this series:

Indians 201: Death Valley National Park

Indians 201: European Colonists and Missionaries in Early Maine

Indians 201: Massachusetts Prior to 1620

Leave a Reply