The Revolutionary War and American Indians

( – promoted by navajo)

In 1776 a group of American colonists signed the Declaration of Independence which condemned King George III for preventing the colonists from appropriating western lands which belong to Indian nations. Among the allegations against the English is the charge that King George has not helped the colonists against the “savages of the interior” (referring to their conflicts with Indian nations.) From the perspective of American Indian nations these were uncomfortable words: if these rebellious British colonies prevailed, Indian nations would have to defend their homelands against an invasion of settlers.

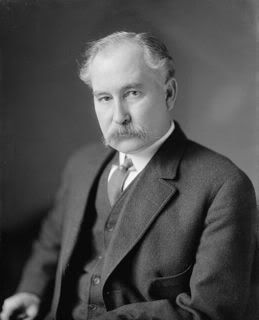

James Wilson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, felt that Indians must give way to progress.

“The whole earth is allotted for the nourishment of its inhabitants, but it is not sufficient for this purpose, unless they aid it by labor and culture. The cultivation of the earth, therefore, is a duty incumbent on man by the order of nature.”

The Revolutionary War divided the Indian nations as both the British and the newly formed United States tried to obtain Indian allies. Most of the Indian nations east of the Mississippi River sided with the British. Those who favored neutrality and those who sided with the colonists often found themselves at odds with the countrymen.

In Massachusetts, the Stockbridge, a Christian composite tribe, formed an entire company for the American Revolutionary Army. They were placed under the command of Captain Daniel Nimham and often acted as scouts for other units. They were issued red and blue caps so that they could be distinguished from enemy Indians. They fought against the British under General Howe at the Battle of White Plains. Several Stockbridge warriors were killed in this battle.

The American forces asked a number of different Indian nations for their support in the war effort. General George Washington asked the Passamaquoddy of Maine to send him warriors. Massachusetts passed a resolution calling for 500 Micmac and Maliseet Indians to be employed in the Continental Army. While Maliseet chiefs Ambrose St. Aubin and Pierre Tomah supported the American cause, many Indians avoided the recruiting efforts.

Both sides wanted the support of the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. In New York, the Sons of Liberty sent a wampum belt to the Iroquois and asked them to intercept British troops coming down the Hudson River from Canada. On the other hand, the British met with the Iroquois in New York to gain their allegiance against the rebellious colonists. Some of the observers noted that the women, and particularly the Mohawk Molly Brant, were the power behind the scenes.

In 1777, the British met with many of the Iroquois nations at Oswego, New York and formally asked them to go to war against the rebellious colonies. In the Iroquois warriors’ council, Joseph Brant argued in favor of going to war, while Red Jacket, Handsome Lake, and Cornplanter felt that this was a family quarrel among the Europeans and Iroquois interference would be a mistake.

One of the basic foundations of the Iroquois Confederacy was that no Iroquois nation should ever fight another Iroquois nation. Four of the six nations-Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk-openly declared their support for the British and their willingness to fight for the British. As a result of this division, the council fire for the Iroquois League of Six Nations at Onondaga was ceremonially covered, symbolically suspending the League. Each of the nations was now free to go their own way with regard to the war between the colonists and English.

The Oneida, a member of the Iroquois Confederacy, were divided over the Revolutionary War. The sachems (chiefs) tended to be pro-British, but there was a strong contingent of pro-American warriors led by Shenandoah. Tuscarora (another member tribe of the Confederacy) leader Nicholas Cusick recruited both Tuscarora and Oneida warriors to fight for the Americans.

For the Iroquois nations, the Revolutionary War was a situation in which, in some cases literally, brother killed brother. At the 1777 Battle of Oriskany, for example, the pro-British Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brant (Mohawk) and Chainbreaker (Seneca) fought against the pro-patriot Iroquois under the leadership of Nonyery Tewahangaraghkan (Oneida).

There is an interesting religious side note to the Battle of Oriskany. Fighting for the Americans were the Oneida and Tuscarora who had been converted to Christianity by Samuel Kirkland, a strong supporter of American independence. On the British side, the Mohawk had been converted to Christianity by John Stuart, an Anglican and supporter of England.

There is another interesting side note with regard to the Iroquois involvement in the war. In New York, a small party of Mohawk under the leadership of Joseph Brant together with a few of their British allies attacked the settlement of Minisink to obtain provisions. One of the Americans, Captain John Wood, was about to be killed when he inadvertently gave the Master Mason’s sign of distress. Brant, a Mason, saw the sign, pushed the warrior aside, and gave Wood the Master Mason’s grip. The following day, Wood confessed to Brant that he was not a Mason. When Wood returned from captivity many years later, one of his first acts was to apply for membership in the Masonic lodge.

In 1778, the newly formed United States negotiated its first Indian treaty with the Delaware. The treaty allowed troops to pass through Delaware territory. In addition, the Delaware agreed to sell corn, meat, horses and other supplies to the United States and to allow their men to enlist in the U.S. army. The treaty also stated that if the Delaware do decide, they might form a state and have a representative in Congress. The idea of statehood for the Delaware was suggested by Chief White Eyes

Emissaries from the Iroquois, Shawnee, Delaware, and Ottawa traveled to the Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River to meet with the Cherokee in an attempt to persuade them to form an alliance against the American revolutionaries. Shawnee leader Cornstalk told them:

“It is better for the red men to die like warriors than to diminish away by inches. Now is the time to begin. If we fight like men, we may hope to enlarge our bounds.”

The Shawnee produced a War Belt, made of wampum which was about nine feet long. Cherokee war leader Dragging Canoe accepted the belt and the warriors joined him in singing a war song.

In spite of the persuasive words of the northern Indians, the Cherokee remained divided on this issue. The older Cherokee, such as Attakullakulla and Oconostota, objected to the war, but some of the younger warriors, such as Dragging Canoe, Doublehead, Young Tassel, and Bloody Fellow, sided with Cornstalk.

For many Indian communities, the Revolutionary War interrupted the fur and hide trade. Indian nations at this time had been incorporated into a globalized economy and had come to depend on many European trade goods. Thus one of the most pressing questions posed by the outbreak of the Revolutionary War for many Indians was not who should govern in America but who would supply the trade goods on which they had come to depend.

While many Indians, both individual warriors and Indian nations, supported the American cause during the war, this did not give them any advantages following the war. In fact Indian support for the new nation did not even earn Indian people a place in the nation they helped to create. For Native Americans, it seemed the American Revolution was truly a no-win situation.