George Washington and the Indians

George Washington is often revered as the first President of the United States. As the first president, he established many of the protocols for the office. From an Indian perspective, his presidency also established much of the basis for the federal Indian policies. Like other non-Indians of this era, he viewed Indians as a vanishing people, or at least a people who at some time in the near future would cease to exist in the United States. Indians were to either die out, migrate, or become totally assimilated.

Before the Revolutionary War:

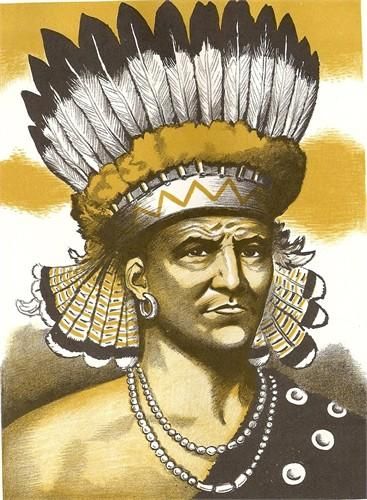

George Washington’s first combat experience came in 1754 as the leader of a combined Virginia and Seneca force which had marched against the French forces in Ohio. The French had constructed Fort Duquesne in an attempt to gain influence over the tribes in the region. Seneca leader Tanacharison (Half King) reported to the British Virginia forces under George Washington what the French were attempting to do. He also provided Washington with a delegation of warriors. The combined Virginian and Seneca forces surrounded a French camp, killing 10 and taking 21 prisoners. When the wounded French leader attempted to explain that he was on a diplomatic peace mission, Tanacharison, who was more fluent in French than Washington, killed him before Washington understood the nature of his message.

Seneca leader Tanacharison (Half King) arranged a council between tribal leaders and George Washington. Washington, realizing that he needed the support of the tribes, explained that the purpose of the British military efforts were to maintain Indian rights to the region and to prevent the French from taking their lands. The chiefs, however, were not persuaded and viewed any alliance with Washington’s troops as a bad gamble.

Following the English victory over the French in 1763, the English King issued a Royal Proclamation which set a boundary line from Nova Scotia to Florida following the Appalachians. This boundary was supposed to separate the Indians from the colonists. The Royal Proclamation temporarily reserved a vast territory as exclusive Indian hunting grounds and curtailed colonial charters at the boundary. The European colonists were forbidden to settle west of the boundary line.

The Proclamation also assumed imperial authority over the Indians, thus claiming the continent while allowing Indians to live upon it at their grace and favor. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 prohibited the purchase of Indian lands by private individuals.Many of the European colonists, such as George Washington, simply viewed the proclamation as a temporary expedient to calm the Indians. George Washington regarded the Indian tribes of the region as temporary: he felt that they were destined to be displaced by the growing wave of European settlers that would soon cross over the Alleghenies seeking to establish themselves on Indian land. The European settlers simply ignored the new line and continued to settle on Indian land, to build blockhouses, and to dare the Indians to force them out.

The Revolutionary War:

When the Revolutionary War broke out, both sides looked to recruit Indian allies. The Continental Congress passed a resolution to call on Indians for support in case of real necessity. Several Indian nations in Maine-particularly the Penobscot and the Maliseet-quickly allied themselves with the colonists feeling that the colonists would recognize their aboriginal rights. In 1776, General George Washington asked the Passamaquoddy of Maine to send him warriors.

In 1778, 30 Stockbridge (a Christian Indian community) soldiers died fighting for the American revolutionaries against the British at White Plains, New York. Among those killed were chief Daniel Nimham. As a result of bravery in this battle, General George Washington promoted Hendrick Aupaumut to the rank of captain.

While many Indians aided the Americans in their struggle for independence, in 1779 George Washington sent 5,000 American troops under the command of General John Sullivan to destroy the villages of the Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca as punishment for aid which they had supposedly given to the British. Washington’s orders are for

“the total destruction and devastation of [the Indian] settlements and capture as many prisoners as possible.”

The American forces made no distinction between those who had been American allies and those who had aided the British. The Americans destroyed 40 villages and 160,000 bushels of corn.

The Constitution and Congressional Action:

The Constitution of the United States was adopted in 1787. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 delegated to Congress the power

“to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes”

Thus dealings with the tribes are to be federal. Congressional action, according to those who wrote the Constitution, was to be superior to state law and Congress was to have the exclusive authority to deal with Indian tribes.

Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 which provided for the administration of the northwestern portion of the former colonies (now the Midwest east of the Mississippi River). Congress viewed the Indian presence in this area as temporary and made it clear that the United States intended to settle the area. However, the Act indicates that the federal government is not to invade or disturb Indian nations unless there is a “just” war. Section 14, Article III of the Ordinance also states:

“laws bounded in justice and humanity shall, from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace and friendship with them.”

At this time, George Washington called for the purchase of land from the Indians rather than driving them by force out of the country. He described Indians as being like the “Wild Beast of the Forest” and the “Wolf” as he viewed them as beasts of prey.

President George Washington:

George Washington became the first President of the new United States in 1789. Like other Americans at this time, he believed that Euro-American culture was more advanced than Indian culture. He believed that Indians would eventually assimilate into the dominant American culture

Under the new U.S. Constitution, the American leadership-President George Washington, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and Secretary of War Henry Knox-assumed that Indian policies were now vested in the federal government rather than in the state governments. Furthermore, they saw Indian affairs being directed by the executive branch. They saw Indian policy as a branch of foreign policy and viewed Indian tribes as foreign nations.

Secretary of War Henry Knox, recognizing that war with the Indians would be prohibitively expensive, and that war without prior negotiation would be unjust, began a policy of negotiation. This reversed the “conquest theory” (that the United States has title to Indian land because of its victory over England) and recognized Indian rights to the land. He felt that it was important for Indians to be introduced to the idea of a love for exclusive property and suggested the appointment of Christian missionaries to live among the Indians as one way of introducing this idea.

Henry Knox lobbied President George Washington to make the reform of American Indian policy a priority of his presidency. Consequently, the two men developed a new Indian policy for the United States. As foreign nations, Indian policy should be part of foreign policy under the Secretary of State, but since Knox had been doing the job and had the information about Indians at his fingertips, they decided it should be under the Department of War. Subsequently, Congress gave authority over Indian affairs to the Department of War.

Knox and Washington viewed treaties with Indian nations as being binding on both parties in perpetuity. The power and the honor of the federal government would be pledged to their enforcement. In addition, all treaties were to contain a provision which would provide the Indians with agricultural implements so that they could make the transition from savagery (meaning hunting) to civilization (meaning farming).

President Washington’s first experience with Indian treaties came in 1789 when Henry Knox persuaded him to make diplomatic overtures to the Creek. Since this would be the first treaty with an Indian nation since the ratification of the Constitution, Washington had to interpret the constitutional requirement to obtain “the advice and consent” of the Senate. He interpreted this to mean that he must appear before the Senate in person prior to the treaty negotiations. The result was uncomfortable for both Washington, who was not an orator, and the Senate. This was the first and last time that a president would appear in person to seek the advice and consent of the Senate on a treaty. Hereafter, treaties would simply be sent to the Senate for ratification after they had been ratified.

In 1790, Seneca leaders Cornplanter, Big Tree, and Halftown traveled to Philadelphia to complain to President George Washington about non-Indian encroachment on tribal lands. Referring to their 1784 treaty, they asked Washington:

“Does this promise bind you?”

Washington guaranteed their boundaries and control of their lands by telling them that

“…all the lands secured to you, by the treaty of fort [sic] Stanwix, excepting such parts as you may since have fairly sold, are yours, and that only your own acts can convey them away.”

The federal government agreed to provide Cornplanter with an annual pension of $250.

Federal and State Conflicts over Indian Affairs:

Secretary of War Henry Knox reported to President Washington that:

“The independent nations and tribes of Indians ought to be considered as foreign nations, not as the subjects of any particular state.”

This set the stage for ongoing conflicts between the states and the federal government regarding the jurisdiction for Indian affairs. These conflicts not only plagued Washington’s Presidency, but have continued until the present time.

Congress passed the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act in 1790 which forbade the private purchase of Indian land; provided for the punishment of non-Indians who committed crimes in Indian country; and licensed those who traded with Indians. Purchase of Indian land was to be done at a treaty council held under federal auspices. Congress clearly viewed Indian affairs as being under federal jurisdiction, not state jurisdiction. It was soon, clear, however, that the states did not agree.

In 1790, the Georgia state legislature announced the sale of 24 million acres of land which they had acquired from the Creek to three private companies, collectively called the Yazoo Companies. President George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox viewed Georgia’s actions as a blow to federal sovereignty and to the assumption that Indian policy is a branch of American foreign policy. Creek leader Alexander McGillivray saw this action as a potential invasion of Creek territory.

Alexander McGillivray and 26 other Creek chiefs signed a treaty with President George Washington in New York. While Washington did not love Indians, he treated the Creek delegation to dinners, parades, and diplomatic ceremonies that equaled, and some say exceeded, those accorded to any European diplomatic mission.

Georgia denounced the treaty as a violation of state’s rights since the treaty stipulated that the Creek Nation would not hold any treaty with an individual state. To reinforce the Creek treaty, President George Washington issued an executive order forbidding private or state encroachments on all Indian lands under treaties with the United States. The Georgia legislature simply defied the proclamation and sold more than 15 million acres of Creek land. In 1794, the Georgia Assembly appropriated Creek lands for the payment of state troops in spite of the fact that these lands had been guaranteed to the Creek by the federal government.

In 1791, the New York state legislature pursued its own Indian policy by authorizing emissaries to visit the Seneca and open up land negotiations. President George Washington raged about this action:

“the interferences of States and the speculations of Individuals will be the bane of all our public measures.”

In 1796, the Penobscot signed a treaty with Massachusetts in which they retained title to the islands for thirty miles above Oldtown, Maine. Maine at this time was still a part of Massachusetts. The treaty was negotiated and signed in violation of both the Constitution and the 1790 Trade and Intercourse Act.

In 1796, President George Washington published an open letter to the Cherokee Nation. Washington promised the Cherokee that the federal government would enforce treaties honorably and ensure Cherokee survival as a people and a nation. Washington describes his commitment to this as both a matter of law and a personal promise. It was clear that Washington meant every word and the Cherokee accepted it as a sacred vow of the federal government. Despite Washington’s sincerity and personal commitment, the promises to the Cherokee were not kept.