Art Museums Discover Indian Art

During the nineteenth and the first part of the twentieth century, American Indian objects that would today be considered works of art were relegated to display in cabinets of curiosity with dinosaur fossils, stuffed penguins, and unusual geological specimens. By the 1930s, however, some museums were beginning to recognize American Indian art as a distinct art style.

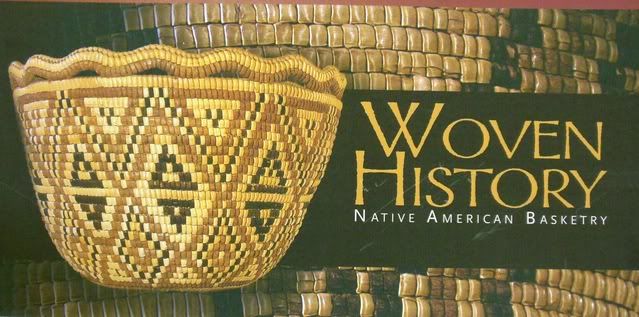

In 1930, the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff held the first Annual Hopi Craftsman Exhibition. Items displayed were required to pass a jury and participants were encouraged to put their individual marks on pieces so that they could build a personal reputation. Initially the Exhibition concentrated on pottery, basketry, and weaving.

In 1931, the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts was presented at the Grand Central Art Galleries in New York City. The exposition was sponsored by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the Secretary of the Interior, and the College Art Association. The organizers of the exposition wanted to show Indian art as a traditional art form. The show included more than 600 pieces of pottery, jewelry, textiles, sculpture, paintings, beadwork, and basketry. According to the show’s catalog, the purpose of the exposition was to give the

“Indian a chance to prove himself to be not a maker of cheap curios and souvenirs, but a serious artist worthy of our appreciation and capable of making a cultural contribution that will enrich our modern life.”

With regard to the Indian artists who participated in the exposition, the news media tended to dwell on the quirks of the “quaint” Indians visiting the big city: according to some reports the Indians were said to be bothered by elevators. On the other hand, there were a number of news reports which respected the artists and their works. From the larger perspective of art history, Indian cultures were in the process of being discovered by American modernists. European surrealists were exhibiting their works next to the works of Native peoples and seeing in this indigenous art an expression of a primordial order that was often lost in traditional Western art.

In 1932, the Whitney Museum in New York bought Pueblo (San Ildefonso) artist Tonita Peña’s painting Basket Dance for $225. This was the highest price paid up to this time for a Pueblo painting. Most Native American paintings at this time were selling for $2 to $25. Her works had been exhibited the year before in the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts.

Tonita Peña (1893-1949) is shown above. She was later know as the Grand Old Lady of Pueblo Art and was one of the most influential Native American women artists of this period. Many of her early works were done in pen-and-ink as professional materials were not readily available to her.

In 1932, the Brooklyn Museum hosted four Navajo and three Pueblo artisans who demonstrated their skills in the museum’s sculpture court. According to the museum, the Pueblos represented “innovators” and the Navajos represented “borrowers.” According to the museum literature:

“With the cultivation of crops as their most important occupation, the Pueblos had built up a rich mythology and symbolic art and a complicated ceremonial life for the purpose of securing rain for their crops. The invading Navajos took over the external features of Pueblo rain ceremonies but attached a quite different significance to them-the curing of the sick.”

With regard to popularizing Native American art, the The New York Times Sunday Magazine in 1932 featured Native American arts and crafts for home interiors. Readers were told how Indian arts and crafts were finding a growing appreciation among home decorators and furniture designers.

The 1933-1934 Century of Progress Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair) featured several Native American artists. San Ildefonso potters Maria and Julian Martinez received the Best in Show award and three noted Navajo artists gave demonstrations: Hosteen Klah, a medicine man who did sandpaintings; Fred Peshlaikai, one of the foremost Navajo silversmiths; and Ah-Kena-Bah, a weaver.

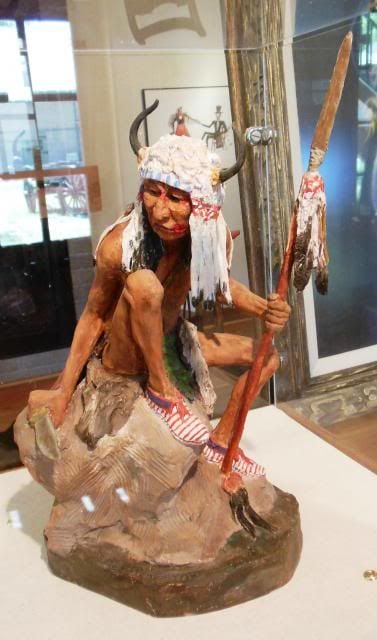

Hosteen Klah (1867-1937) is shown above.

The 1930s are well-known as the era of the First Great Depression and both the federal government and the museums recognized the potential for Indian art as a form of economic development. In 1934, the Seneca Arts and Crafts Project was organized by Arthur Caswell Parker (who was himself Seneca) and the Rochester Museum. According to its original proposal:

“The Rochester Municipal Museum proposes a project by which the almost extinct arts and crafts of New York Indians may be preserved and put on a production basis in order that such activity and products may contribute to the relief and self-support of the said Indian population.”

The Project was set up in an abandoned school and the artists set about reproducing traditional items. Illustrations and photographs from museum collections and archaeological sites were used as guidelines. Parker was intent on maintaining consistency with the ethnographic record. Overall, the artists produced more than 5,000 separate works of art. For the museum, the Project raised the museum’s profile during a time of economic cutbacks and uncertain visitor numbers.

Not all Indian art was appreciated during the 1930s by non-Indian authorities. In 1936, a government restoration project at the Mission San Fernando uncovered at least two murals painted by Tongva Indians which depicted a hunting scene and other non-Christian themes. Church officials ordered the murals obliterated.

In 1937, Mary Cabot Wheelwright founded the Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art in New Mexico. She had been permitted to record many of the songs of Navajo singer Hosteen Klah and erected the museum to preserve his medicine knowledge and his sacred objects. The museum is now known as the Wheelwright Museum.

In 1938, Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton, one of the founders of the Museum of Northern Arizona, stressed the importance of making Hopi silver different from that of other tribes. She wrote:

“In order to help the Hopi silversmiths to visualize our idea of Hopi design and to show them how to make use of and adopt pottery, basketry, and textile design to various silver techniques already practiced, we have created a number of plates done in opaque water color on gray paper.”

The 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco included an exhibition of Indian art in the United States and Alaska which brought national and international exposure to contemporary Native American art. The exhibit’s aim was–

“to present to the public a representative picture of the various areas of Indian culture in the United States and Alaska, and at the same time to give the living Indian a chance to find a new market for his products.”

Once again the emphasis was on Indian art as a form of economic development. Sales rooms at the Exposition exhibited Native American fine arts in contemporary settings, thus demonstrating their suitability for modern home decorations. Sixty-two Native Americans participated in the exhibition and the material exhibited ranged from sandpaintings to totem poles. Hopi artist Charles Loloma painted one of the wall murals which showed Pueblo dancers.

Pueblo wall murals also proved popular in other locations and venues. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, a series of mural panels were painted on Maisel’s Indian Gift Shop by Tewa artist Pablita Velarde.

The potential boom in Native American art promoted by the museums and the media during the 1930s was, however, interrupted by World War II. While the stage was set for increasing popularity, and profitability, for Native American art at this time, it would be another two decades before it would come to fruition.