The Hopi Reservation

The Hopi had lived in their mesa-top villages in what is now northern Arizona for many centuries before the United States acquired the right to govern the area. They did not, however, sign a treaty with the United States and therefore did not reserve a portion of their homelands for themselves.

The designation “Hopi” is a contraction of Hopi-tuh which means “peaceful ones.” While the United States has insisted on dealing with the Hopi as if they were a single tribe they are actually about a dozen independent pueblos.

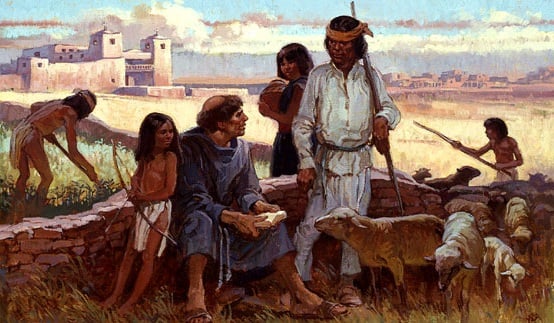

The Hopi village of Walpi is shown above.

The Hopi reservation in Arizona was created in 1882 by executive order of President Chester A. Arthur. The Executive Order which created the reservation allowed the Hopi only the use of the lands and did not recognize their ownership of the lands. The reservation was totally surrounded by the Navajo reservation and excluded the major Hopi village of Moenkopi. The Hopi were not consulted in the creation of their reservation and its boundaries ignored a larger area that was settled and claimed by the Hopi. The rather arbitrary boundary lines created by the American government did not please the Hopi. Their ancestral homeland had encompassed hundreds of miles of land and had ranged from near what is now the New Mexico-Arizona borderlands, west to the Grand Canyon, and south to the Mogollon Rim. The Hopi clan petroglyphs and religious shrines had demarcated this area for many centuries.

J. H. Fleming was appointed as the Indian agent for the Hopi. Regarding the Hopi ceremonial dances, he felt that-

“The great evils in the way of their ultimate civilization lie in these dances. The dark superstitions and unhallowed rites of a heathenism as gross as that of India or Central Africa still infects them with its insidious poison.”

There were at least 300 Navajo living in the area which was designated as the Hopi Reservation. They were not asked to leave.

During the 19th century, the United States government policies with regard to American Indians called for them to be totally assimilated into American culture and for any remnants of tribal culture to be eradicated. As a part of this assimilation policy, the United States built a boarding school for the Hopi at Keams Canyon in 1887. The federal government set quotas for attendance from each of the Hopi villages. However, the people in the village of Oraibi refused to send their children to the school.

Three years later, the Hopi in the village of Oraibi were still refusing to send their children to school. The Tenth Cavalry was sent in to “insure peace”. The military troops invaded the village and “captured” 104 children for the school.

At this time, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs arranged for Oraibi leader Loololma and other Hopi leaders to visit Washington, D.C. where they were encouraged to accept allotment, Christian missionaries, and American schools. Loololma returned to the Hopi supporting the American programs.

In 1890, representatives from the Indian Office met with the military at the boarding school at Keam’s Canyon, Arizona to discuss a quota system to force Hopi children to attend the school. The Army was to implement and enforce the program. In the Hopi village of Oraibi, Loololma supported the government program and was imprisoned in a kiva by those who opposed it. Federal troops invaded and released Loololma.

In 1891, the United States sent surveyors to the Hopi reservation to divide the land into individual parcels under the Dawes Act. However, under Hopi tradition land is owned by the clan rather than the individual and the Hopi rejected the attempt to implement the Dawes Act. At this time, the Hopi village of Oraibi was divided into two factions labeled the “hostiles” and the “friendlies” by the Americans. The Hopi “hostiles” pulled up the survey stakes as soon as the surveyors left and the federal government ordered the arrest of the outspoken chiefs at the village of Oraibi who had opposed allotment. The troops were met by armed “hostiles” and the Hopi made a formal, ceremonial declaration of war against the United States.

The soldiers called for reinforcements, including Hotchkiss machine guns. The soldiers took eleven prisoners (the war chief and ten other leaders). Five of the prisoners were taken to Fort Wingate where they were forced to tend the gardens of the American officers. The Hopi prisoners did not stand trial nor were they provided with any legal protections.

In 1893, the Mennonite Church sent Reverend H.R. Voth to establish a mission in the Hopi village of Oraibi. Voth proselytized in the streets and forced his way into the kivas.

In 1894, conservative Hopi in the village of Oraibi continued to voice opposition to the requirement to send their children to school. Federal troops were called in and 19 Hopi men were arrested and imprisoned at Alcatraz Island. Among those arrested and imprisoned was Lomohongyoma.

The Western Navajo Reservation and Agency was established in 1900 by Executive Order. The new reservation includes Tuba City, Moenkopi, and Willow Springs. In addition to the Navajo, the new reservation includes both Hopi and Paiute whose presence in the area predates that of the Navajo.

To encourage tourism into the southwest, the Santa Fe Railway promoted the Hopi Snake Dance as a tourist attraction and in 1900 published a pamphlet on the dance written by a Smithsonian anthropologist, Walter Hough. In the pamphlet, Hough reassured the tourists that while the Hopi continued to perform their Snake dance, they were not dangerous. According to Hough, Indians were living examples of the childhood of man. While the Religious Crimes Code had made ceremonials such as the Snake Dance illegal, it was not enforced against the Snake Dance because the railroad promoted it and the tourists demanded to see it.

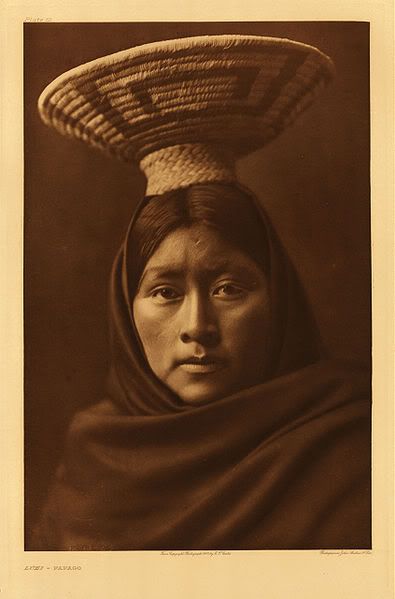

A Hopi women’s dance is shown above.

In 1900, Charles E. Burton became the Indian Agent for the Hopi. He ordered that all Hopi boys and men have their hair cut. Those who did not cut their hair voluntarily were to have it cut by force.

In 1901 Tawaqwaptiwa replaced Loololma as the leader of the “friendlies” in the Hopi village of Oraibi. Tawaqwaptiwa was the son of one of Loololma’s sisters.

In 1903, the Indian Agent for the Hopi with a number of heavily armed Navajo police raided the village of Oraibi during the pre-dawn hours searching for children who were not attending school. Men, women, and children were dragged from bed, some naked, some wearing little clothing, and forced to walk, many barefoot, through the snow and ice to the school. They were held in the school all day. The Indian agent told the Hopi that they were to have their children in school, every day, regardless of the weather conditions.

As a result of this raid and other abuses against Hopi children-lack of food, clothing, and medical care-Belle Axtell Kolp resigned as teacher and took the story to the media and to the Sequoia League.

In 1904, the Indian agent for the Hopi forced a number of men to have their hair cut. This was an act which disregards the ceremonial purpose of long hair. Long hair among the Hopi men was a symbol of the falling rain for which they prayed. For the Hopi, for a man to have his hair cut during the growing season was tantamount to asking that the corn stop growing.

In 1910, the federal government once again attempted to allot Hopi lands into small parcels of individually owned land. Once again the program fails. The Hopi do not share the American obsession with private property and farm land is clan owned.

In 1911, Leo Crane, the new superintendent for the Hopi reservation, requested a cavalry escort for a tour of the reservation. He found that four-fifths of the reservation had been taken over by Navajo and their sheep.

In 1911, a detachment of Black troops under the leadership of Colonel Hugh Scott arrived at the Hopi reservation to help superintendent Leo Crane force the children of the village of Hotevilla to attend school. Colonel Scott went to Hotevilla to interview Youkeoma, the village chief. The troops stood by while Crane and his staff searched the village for children. Sixty-nine children were placed under guard to be taken to the boarding school at Keams Canyon.

Crane and the Black troops next stopped at Shongopovi where village leader Sackaletztewa opposed sending children to school. Using the troops as a way to intimidate the people, Crane searched the village and found three children.

In 1915, the Hopi boarding school at Keams Canyon was judged to be in dangerous condition and was closed. The children were enrolled in reservation day schools.

In 1917, a news service cameraman defied the Hopi rule against taking motion pictures of the Hopi Snake Dance. He was chased through the desert and his camera is confiscated. After reporting the incident to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, superintendent Leo Crane received the order that no photographs should be permitted. The ban on photography continues today.

When the Hopi reservation was created it was named the Moqui Agency, a term which was offensive to the Hopi. In 1917, the reservation superintendent recommended that the name be changed from Moqui to Hopi. In 1923, the name was officially changed.

In 1920, the non-Indian principal of the Oraibi School interrupted a Hopi ceremony when he saw a clown dancer with a huge artificial penis. In the words of the principal, he stopped the ceremony and told the dancer

“that if he ever did a thing like that again, I would put him in jail. He told me that he did not know it was wrong, that it was a Hopi custom.”

In 1921, Robert E. L. Daniel, the superintendent of the Hopi reservation, together with eight employees and seven policemen, all armed with pistols and buggy whips, went to the village of Hotevilla. The people were then forcibly stripped and dipped in sheep dip (black leaf 40). The superintendent wrote:

“We prepared their baths at the proper temperature, bathed them, and boiled and dried their clothes for them while they were being bathed. Yet they had to be driven or dragged to the tub, and forced into it like some wild beast, unblessed with human intelligence. Pure unadulterated fanatical perversity is the only explanation.”

Reports by others differ from that of the superintendent. In the words of Violet Pooleyama:

“They started putting our men and boys in it just as if they were sheep. They took the women and girls and put them in it, too. When the women fought with them they often threw them into the sheep-dip clothes and all. Sometimes they tore the clothes off the women and girls.”

According to the superintendent, the Hopi were dipped because they were “dirty” and they had lice. On the other hand, the Hopi feel that they were forced through this humiliating process as a form of punishment for refusing to send their children to school.

The government officials used baseball bats to club men who resisted and ten of the Hotevilla men were taken to jail in Keams Canyon for resisting. In one instance, they knocked a man out for two hours. When he came to, they handcuffed him, hung him from the saddle of a horse, and dragged him to Keams Canyon.

In 1922, word of the efforts of the Indian Office to prohibit Pueblo religions in New Mexico reached the Hopi. Several Hopi leaders decided to meet in Winslow, a non-Indian town which is located off of the reservation. They feared that if they were to meet on the reservation that the Indian Office officials would arrest them. Meeting with the Hopi was the distinguished writer James Willard Schulz.

Schulz heard the Hopi complain about threats from government if they continued their religion. One elder stated that he would rather be shot down by the government while doing his religion than try to live without it. The Hopi were determined to stand firm and to continue to observe their traditional ceremonial calendar.

Five Hopi visited Washington, D.C. in 1926 and presented four tribal religious dances before an audience of 5,000. The Hopi wanted to show people, including Vice President Charles Dawes and two Supreme Court justices, that their ceremonies were not cruel rites.

The Indian Office in 1930 decided that it was time for the Hopi and the Navajo to settle their differences by having delegates from both tribes meet in Flagstaff, Arizona. The Navajo had 11 delegates: 5 were Navajo from Hopi lands and 6 were Navajo from the western portion of the Navajo reservation. The Hopi had 13 delegates: 10 were from the 1882 reservation area and 3 were from Moencopi (a Hopi pueblo located outside of the reservation area). The arbitrator from the federal government told the delegates that this was an opportunity for the two tribes to resolve their land, grazing, and water problems. The conference, however, settled nothing.

In 1936, only 20% of the Hopi voted on tribal reorganization under the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. Less than 15% of the total population supported reorganization, but the act passed and the entire Hopi Reservation was reorganized. The Hopi who opposed the establishment of a single, overall tribal council simply abstained from voting on the issue, a traditional way of showing opposition. As a result, many traditional village leaders refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new tribal council.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs appointed anthropologist Oliver La Farge to write the constitution and bylaws for the Hopi Tribe. The constitution called for a one-house legislature with a tribal chairman and a vice-chairman. LaFarge proposed the Hopi constitution because he was concerned about what he perceived as the fragmentation of Hopi culture. He apparently did not realize that a centralized government is foreign to Hopi tradition. Despite resistance to a unified Hopi government, a tribal council was established and all of the villages, with the exception of Oraibi and Hotevilla, sent representatives.