Indian Farming in Massachusetts

While the English history of the colonization of Massachusetts often characterizes the Indians as nomadic hunters with no claim to the land, it is interesting to note that the first action of the Pilgrims when they landed in 1620 was to rob an Indian grave of the corn offerings which had been left there. Corn, or maize, as most people know, is not something hunted by nomads, but is a domesticated plant. While the first English colonists survived in the beginning on plant foods raised by the Indians, they often failed to see the Indian fields, as they didn’t look like English fields.

By the time the Europeans arrived on this continent Indian people had three major agricultural crops: maize (corn), beans, and squash. Beans of many different colors and textures were used in many different ways and were added to many foods. Corn was a variety known as northern flint which had eight-rowed, multicolored ears. As with other eastern tribes gourds, strawberries, pumpkins, watermelons, passionflower, Jerusalem artichoke, and tobacco were important crops for the Massachusetts tribes.

Corn had been originally domesticated in Mexico and had diffused to New England by about 2000 years ago. The people at this time already understood agriculture and plant domestication for they had been raising local plants for about a millennium at this time.

Fields were initially cleared by slash-and-burn methods. Fires would be placed around the bases of standing trees which would burn the bark and kill the tree. Later the dead tree would be felled, often knocking down other dead trees as it fell. The clearing was often done by large parties of men and women.

The use of fire as a land management tool involved a carefully controlled ritual process which purified the environment. In order to control the fires and make sure that they didn’t spread into the wetland, Indian people dug ditches. The burning also enriched the land and helped to balance the soil.

The size of the fields varied by region and by the size of the village. A village of 400 people, for example, might clear 350-600 acres for its farms. The fields could generally be used for eight to ten years before there would be a noticeable decline in fertility. After that time the fields would be fertilized with fish and seaweed and/or new fields would be created by burning the woods. Eventually the fields would be abandoned and allowed to go fallow for a generation or so. It was not uncommon for a village to move after 15 to 20 years in order to be closer to the new fields.

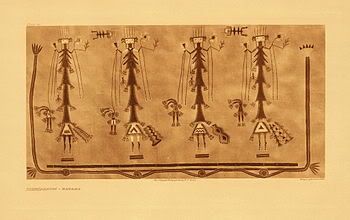

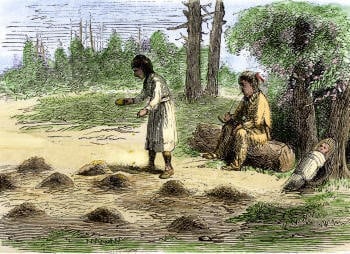

Once an area had been cleared, earth mounds or hills were constructed about four or five feet apart. Kernels of corn and beans would then be planted in the mounds. The corn stalks would later be used by the bean vines as a pole. In the spaces between the mounds, the people would plant squash, gourds, and tubers. The squash vines would trail alongside and over the mounds, protecting the roots of the corn plants and preventing weeds from establishing themselves.

Indian agriculture was not the orderly expression of human domination over nature which was found in European landscapes. The fields which had been carefully planted by the Indians looked like a wilderness to the English invaders.

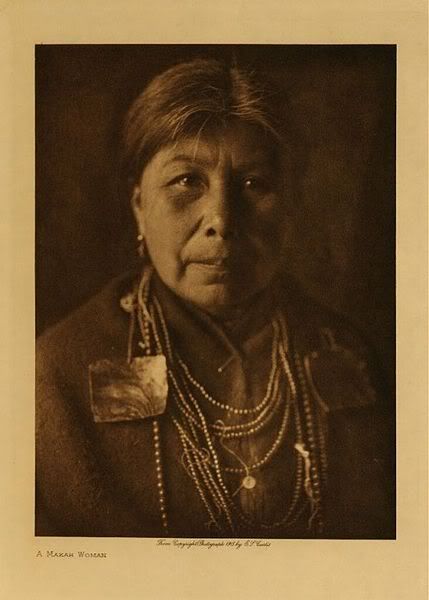

Another major difference between Indian and European agriculture involved labor. First, Indian agriculture was less labor intensive. Second, the planting and harvesting was done by the women, who were considered the owners of the foods which they raised.

Hoes for preparing the ground and weeding used the shells of horseshoe crabs, clams, the scapulae from deer, or turtle shells. Small huts were often constructed in and around the fields. From these huts, children would watch the fields and scare off any birds which threatened the plants. Among some tribes, tame hawks were also used to frighten the birds away.

Planting was timed by the disappearance of the constellation Pleiades from the western horizon and harvesting began with its reappearance in the east. These astronomical observations mark the length of the frost-free season in the area.

Once harvested, the crops were stored in large pits lined with bark or mats. The pits were then covered with logs and earth. In some instances, these pits were inside the lodges.

With regard to the efficiency of Indian agriculture in Massachusetts, it is generally estimated that one Indian woman could raise anywhere from 25 to 60 bushels of corn by working an acre or two. This was enough to provide at least half of the annual caloric requirements for a family of five. When corn was combined with the other foods which they raised, women may have contributed as much as three-fourths of a family’s total subsistence needs.

Corn was prepared in a number of ways, including making hominy of the kernels and making a stew of beans and corn called succotash. Corn meal ground in wooden mortars was boiled or baked in the shape of cakes or round balls. When people travelled, they often carried with them parched cornmeal which could be easily and quickly mixed with water to become a food known as nocake. This was the aboriginal equivalent of fast food.