Mount Rushmore

While Europeans tended to build the places they considered to be sacred-churches, statues, memorials-for American Indian people sacred places were often not places constructed by humans, but places which were naturally sacred. In looking at the landscape around them, Indian people did not see a landscape that needed changing, nor did they see it as a landscape which they were to dominate: rather, they saw a landscape filled with living things. The living things within this landscape included the plants and animals, as well as the rivers, the rocks, the mountains, and the hills. Sacred places in the landscape were often portals through which Indian people could make contact with the sacred.

The Black Hills in South Dakota is an area which is historically linked to several tribes, including the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa. As a sacred area, it was used for making contact with the spirit world and obtaining spiritual power. It was here that many Indians conducted ceremonies such as the vision quest, the Sun Dance, and others. It was here that they gathered the sacred medicines-the plants-that they needed for healing and for ceremonial use.

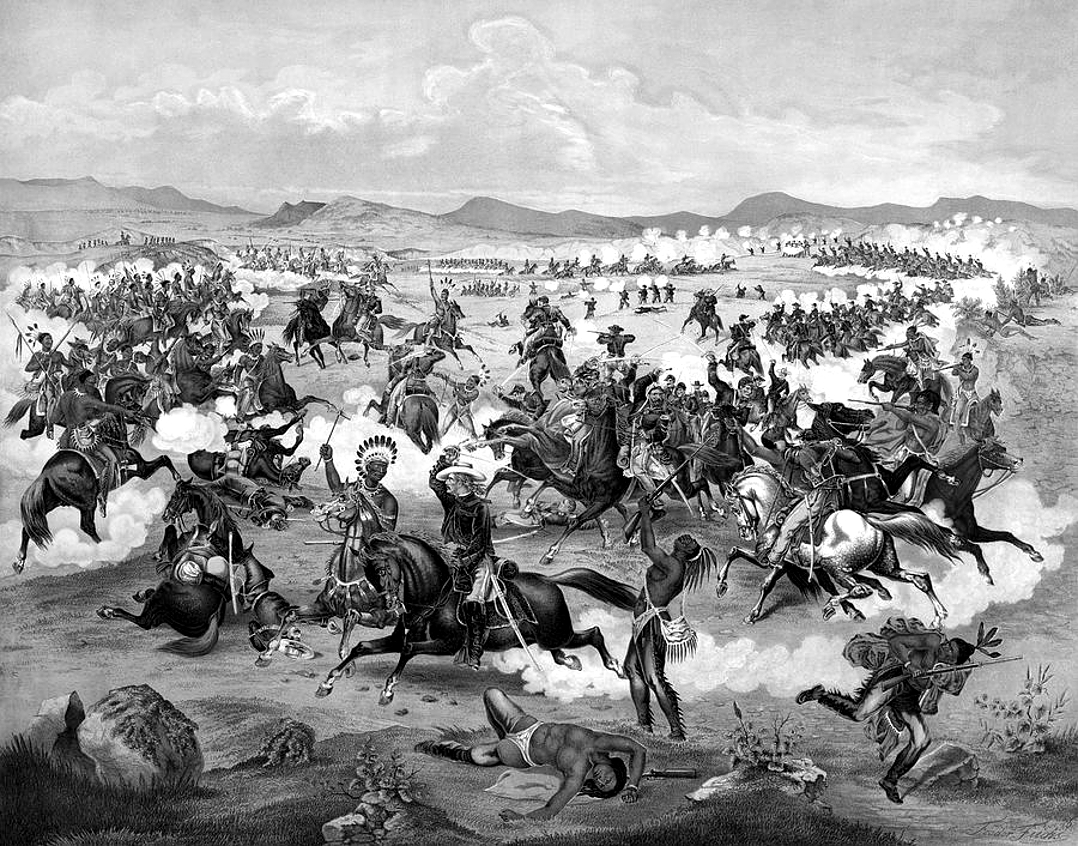

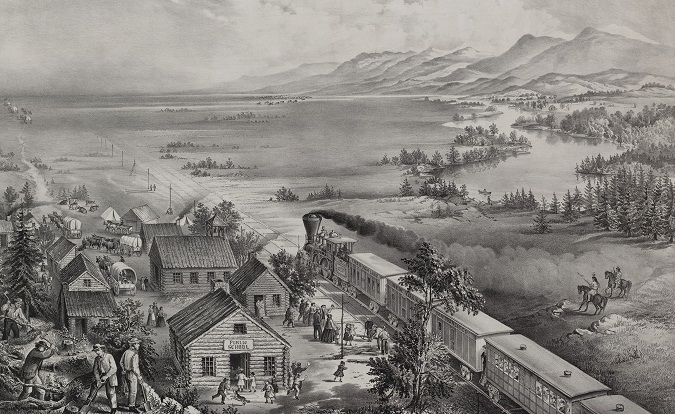

By the 1870s, Americans were spreading rumors that that Black Hills were unoccupied, that they were an area which Indian people did not use. Illegal expeditions into the area somehow ignored all of the Indian hunting parties which they encountered, and which were reported in their journals, and told of an empty area waiting for “development” by non-Indians who would redeem the area from its paganism and make it a part of modern America.

The theft of the Black Hills from the Sioux has been widely reported by both historians and the popular media. The theft, however, involved more than just taking the land: it also involved renaming it. All of the geographic features within the Black Hills had Indian names in 1877, but over the next couple of decades these names were replaced by non-Indian names.

In 1884, New York City attorney Charles E. Rushmore came to the Black Hills to check on legal titles to some properties. On coming back to camp one day, he asked Bill Challis about the name of a mountain. Bill is reported to have replied:

“Never had a name but from now on we’ll call it Rushmore.”

With that offhand comment, the mountain known to the Sioux as Six Grandfathers became Mount Rushmore. The Sioux name had been an important part of their oral tradition and their association with the land. The new name reflected the American lack of concern for the history of the land and the importance of attorneys in their society.

The wealth generated from the gold and the cattle in the Black Hills was not enough to satisfy American greed. By the 1920s, people were looking for new ways of exploiting the Black Hills. In other parts of the country, tourism was proving to be an economic asset, and so, in 1923, Doane Robinson, the South Dakota state historian, came up with an idea to bring tourists (and their money) into the state. His idea was to commission a sculptor to transform one of the tall narrow, granite rock formations in the Black Hills into memorials of major figures from the mythic narrative of the American west. In his vision, he saw giant memorials to heroes such as George Armstrong Custer, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and perhaps the Sioux chief Red Cloud, which would stand along a new highway and lure tourists away from Yellowstone National Park.

The next problem was how to bring the vision into reality. To solve this, Robinson turned to Gutzon Borglum, the son of Danish Mormon immigrants who had made the ten-week trek along the Mormon trail through Indian lands to Salt Lake City. Borglum was one of the most famous sculptors of the time. Borglum had been involved with the carving of a massive bas-relief monument to the heroes of the Confederacy at Stone Mountain, Georgia. Borglum was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and Stone Mountain was used as a site to revitalize the Klan.

Robinson had initially envisioned the carvings on a series of geological features known as “The Needles,” but Borglum found them unsuitable for carving and selected the Six Grandfathers (Mount Rushmore) instead. The new plan was assailed by naturalists who pointed out that it would desecrate the natural beauty of the Black Hills. Robinson replied:

“God only makes a Michelangelo or a Gutzon Borglum once in a thousand years.”

Borglum changed the original vision of the project and proposed a “Shrine of Democracy” which would focus on Presidential portraits. He would later state:

“The purpose of the memorial is to communicate the founding, expansion, preservation, and unification of the United States with colossal statues of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt.”

In 1926, Borglum began carving the faces of four presidents out of a mountain in the Black Hills, land sacred to the Lakota people. The sculptor, who admired Manifest Destiny and saw the conquest of the Lakota and the theft of their sacred land as justifiable, dedicated the sculptures to the Expansion of the United States. From Borglum’s perspective, Manifest Destiny, an expression of racial superiority, was an expression of the rightful order of the world.

The following year, President Calvin Coolidge dedicated the construction of the monument to Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. While the Black Hills were sacred to the Sioux and other tribes, Coolidge made no mention of Indians in his dedication speech.

In 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt dedicated the nearly completed monument to Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt at Mount Rushmore. As with the earlier Presidential dedication, the President made no mention of Indians. The general public who read about the new monument, and the tourists who came to it, were oblivious to the fact that Mount Rushmore had once been Indian land, and that it was still sacred to them.

From the Indian perspective, the monument at Mount Rushmore was a symbol of the dominant culture’s arrogance, racism, and spiritual insensitivity. Carving icons of Presidents who were known for their insensitivity to Indian issues into a living sacred mountain would be similar to painting anti-Christian graffiti inside of cathedral, or anti-Semitic symbols inside a synagogue.

In 1970, a group of about 20 Sioux from the Pine Ridge Reservation under the leadership of Leo Wilcox, a tribal council member, asked to conduct a prayer vigil at the amphitheater at Mount Rushmore. The request was granted. The group explained to tourists and the news media that they had come to protest the failure of the United States to return land taken from the Pine Ridge Reservation for a gunnery range during World War II. They pointed out that Mount Rushmore, a part of the Black Hills, had been illegally taken from them a century earlier.

In a separate demonstration, members of the American Indian Movement demonstrated at Mount Rushmore. Several of them camped on the top of the monument just behind the head of Theodore Roosevelt. A highly respected Sioux spiritual leader, Frank Fools Crow, came to Mount Rushmore and performed a ceremony to purify the land. In doing this ceremony, he re-established the Sioux religious relationship with Mount Rushmore.

In 1971, the American Indian Movement symbolically renamed the monument Mount Crazy Horse. Sioux spiritual leader John Fire Lame Deer planted a prayer staff on top of the mountain. From the viewpoint of AIM and many Native Americans, Mount Rushmore should be considered as the Shrine of Hypocrisy rather than as the Shrine of Democracy. Mount Rushmore symbolizes to them the treaties broken by the United States.

By the end of the twentieth century, there was no doubt that Mount Rushmore was a successful tourist attraction. The non-Indian businesses in the area were earning about $100 million annually. This prosperity was made possible by an initial investment of about $1 million in federal tax money. Just 60 miles east of the monument, however, the Pine Ridge Reservation, home to many of the Sioux who had been the aboriginal owners, was one of the poorest areas in the United States with an unemployment rate of about 80%.

In 2004, Gerard Baker (Mandan/Hidatsa) became the first Native American superintendent of the park. He had previously been superintendent at the Little Bighorn Battlefield in Montana. When he was offered the position at Mount Rushmore, he called the elders and asked their advice. He was expecting them to tell him not to take the job, but instead was told that this would be a good place to start the healing.

Gerard Baker is pictured above.

Under his leadership, Mount Rushmore opened more avenues of interpretation and moved beyond the single focus on the four Presidents. Baker opened up a dialogue with Native American groups, asking them for feedback and input about the monument. As a result, Heritage Village, a small cluster of Sioux tipis, was established at the monument. During the work week, Native Americans provided demonstrations of Sioux culture and handicrafts. They also provided insights into the aboriginal Sioux culture.

In 2008, Baker invited several tribal elders to a tribal council held on the park grounds of Mount Rushmore. In the council the park rangers and staff listened to the concerns and issues of the elders. Three main ideas came out of this dialogue: (1) to place Sioux language translations on several signs as a way of indicating the Indian presence, (2) to distribute pamphlets with an accurate description of Sioux culture and spirituality; and (3) to have Native American college students collect oral histories from elders about the park.

Baker, who suffered a stroke in 2009, retired early from the National Park Service in 2010.