The North-West Mounted Police

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was formed in 1873 to administer law and order in the Northwest Territories (present day Alberta and Saskatchewan). The Mounties, as they came to be called, used consultation and negotiation to avert conflict rather than seek it.

In Alberta, one of the concerns was to put a stop to the illegal liquor trade to the Blackfoot and other Indians. The infamous Fort Whoop-up, located in Alberta, supplied whiskey to both Canadian and American Indians. Shortly after the establishment of Fort Macleod in Alberta, five men were arrested and tried for having liquor in their possession. This resulted in fines and confiscation of their equipment and supply. The arrest of the whiskey traders had an immediate effect upon the relationship between the NWMP and the First Nations peoples. Within a year, the whiskey trade had stopped. With the sale of alcohol halted, the Indians made rapid strides in restoring order to their lives and replenishing their horse herds.

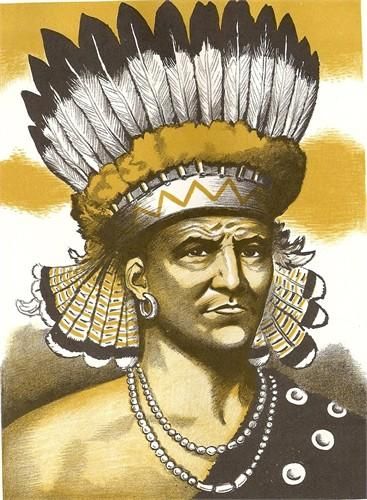

When the NWMP first arrived at the Oldman River in Alberta to establish Fort Macleod, the members of the Blackfoot Confederacy were a little concerned about their presence. They showed neither hostility nor friendship in the beginning. In order to establish friendly relations with the tribes of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Commissioner Macleod met with tribal members. Macleod and Chief Crowfoot reached a gentlemen’s agreement to work together to maintain peace in the area. Chief Crowfoot spoke:

“My brother, your words make me glad. I listened to them not only with my ears but with my heart also. In the coming of the Long Knives, with their firewater and quick-shooting guns, we were weak and our people have been woefully slain and impoverished. You say this will be stopped. We are glad to have it stopped. We want peace. What you tell us about this strong power which will govern good law and treat the Indian the same as the white man, makes us glad to hear. My brother, I believe you, and am thankful.”

Unlike the American military approach to Indians which relied on hard power (i.e. the use of superior numbers and firepower) to force Indians to their will, the NWMP sought a semblance of fairness in their dealings with the tribes. Unlike the situation south of the border, the NWMP administered justice for both Native peoples and non-Native peoples. While crimes against Indians in the United States were ignored by authorities, the NWMP sought justice regardless of whether the victim was Native or non-Native.

By 1876, the North-West Mounted Police were operating out of four stations and collateral outposts. Fort Macleod was built in southern Alberta to offset American incursions in the whiskey and fur trade. Fort Walsh was established 160 miles to the east, just across the provincial border in Saskatchewan. The presence of Forts Macleod and Walsh virtually ended the liquor traffic within a year.

The Mounties and the Sioux:

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana, a number of Sioux fled into Canada to escape the American army. In Saskatchewan, North-West Mounted Police superintendent James Walsh visited the Sioux refugees at Wood Mountain. He estimated that the group had 2,900 people (500 men, 1,000 women, and 1,400 children), along with about 3,500 horses and 30 U.S. government mules. The Indians told him that they were looking for peace and that they had been driven from their homelands by the U.S. army. Walsh instructed the Indians on the law as it would affect their stay in Canada and was assured by the chiefs that they would not use Canada as a base for renewed hostilities against the Americans.

In 1877, Four Horns, a civil and spiritual chief, led his Sioux band of 57 lodges across the border from the United States seeking refuge in Canada. Traveling with them was a band of Yanktonai under Medicine Bear from the Fort Peck Agency in Montana. The Indians were destitute and reported that they had to consume their horses during their march to Canada. North-West Mounted Police superintendent James Walsh met with them and explained the conditions under which they might remain in Canada.

That same year, Sioux leader Sitting Bull brought 135 lodges of his people north from the United States to find refuge in Canada. Travelling with Sitting Bull was a small band of Sans Arc Sioux under Spotted Eagle and Minneconjou Sioux under Swift Bird. They settled in the White Mud River area in Saskatchewan. Here they found that buffalo still roamed the plains in greater numbers than in the United States.

Major James Walsh of the North-West Mounted Police met with Sitting Bull and told him that the Sioux would now have to obey the queen’s laws and in return they would receive the queen’s protection. He warned the Sioux that they were not to return to the United States to hunt or to steal. Sitting Bull agreed to the terms offered by Walsh and declared his intent to remain in Canada. Major Walsh genuinely felt that the Sioux had been badly treated by the United States.

Under pressure from both the United States and Canadian governments, North-West Mounted Police superintendent James Walsh attempted to meet with Sioux leader Sitting Bull to convince him to meet with an American delegation to discuss his return to the United States. Sitting Bull’s son had just died and the chief was in mourning and not interested in a council.

At this time, three Nez Perce warriors (Half Moon, Wep-sus-whe-nin and Wel-la-he-wite) arrived asking the Sioux for help in a battle against the American army which was taking place just south of the border. The Nez Perce, a Plateau area tribe, had never been Sioux allies and had often engaged in battle against them. The Nez Perce who arrived at the Sioux camp did not speak Sioux and were not fluent in Plains Indian sign language. They tried to indicate Snake Creek (the location of the battle) using the signs for “water” and “creek”, but the Sioux thought they were talking about the Missouri River. This was a long distance away and the Sioux felt that it was too far away for them to be able to assist the Nez Perce. The arrival of three more Nez Perce men-Peopeo Tholekt, Koo-sou-yeen, and James Williams-helped straighten out the confusion. Major Walsh cautioned the Sioux that if they went to the aid of the Nez Perce they would lose their privilege to live peacefully in Canada.

The Sioux finally met with North-West Mounted Police superintendent James Walsh and gave him their response to his request that they meet with an American commission:

“Why do you come and seek us to go and talk with men who are killing our own race? You see these men, women, and children, wounded and bleeding? We cannot talk with men who have blood on their hands. They had stained the grass of the White Mother with it.”

However, Walsh convinced Sitting Bull and 25 others to come with him to Fort Walsh.

At Fort Walsh, the Sioux met in council with an American delegation. The Sioux leaders included Sitting Bull, Bear’s Cap, Spotted Eagle, Whirlwind Bear, Flying Bird, Iron Dog, Medicine Turns-around, The Crow, Bear that Scatters, Yellow Dog, and Little Knife. Only Bear’s Cap shook hands with the Americans. Traditionally this type of council meeting would begin with a pipe ceremony, but this was not done.

The Americans told the Sioux that none of those who had surrendered had been punished for hostile acts and all had been received as friends. In offering peace with the Sioux, the Americans asked that they give up their guns and horses, conditions which were not acceptable to the Sioux.

Sitting Bull responded to the Americans by telling of his affection for Canada and even pausing to shake hands again with the Canadians. He concluded:

“You come here to tell us lies, but we don’t want to hear them. Go back home where you came from.”

Among those who addressed the American delegation was The One that Speaks Once, the wife of Bear that Scatters:

“These are the people that I am going to stay with and raise my children with.”

The Americans were insulted and offended by allowing a woman to speak to them in council.

In 1880, Major Walsh, the Northwest Mounted Police officer who had been dealing with Sitting Bull’s Sioux was reassigned. Sitting Bull had trusted Walsh and Walsh had a genuine concern over the fate of the Sioux refugees. Lief N.F. Cozier replaced him and began to pressure the Sioux to return to the United States. He persuaded the young Sans Arc Sioux leader White Eagle of the futility of staying in Canada.

In 1888, the superintendent of the North West Mounted Police reported that there were now about 170 Sioux living in the area around Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. He reported that they were primarily Minnesota Sioux who did not have a treaty with Canada.

Riel Rebellion:

In 1885, the Riel Rebellion broke out in Saskatchewan. The Métis, angered by the refusal of the Canadian government to confirm their riverlot claims along the Qu’Appelle and South Saskatchewan Rivers, organized their own provisional government with Pierre Parenteau, Sr. as president, Gabriel Dumont as military adjunct, and Louis Riel as people’s council.

The war breaks out at Duck Lake when Métis warriors along with their Cree and Sioux allies meet the North-West Mounted Police and a group of volunteers at Duck Lake. Within twenty minutes, the Mounties were defeated and began to pull out. The Métis and their Indian allies began to pursue them, when Louis Riel rode in front of the firing line and yelled:

“Let them go. We have seen enough bloodshed today.”

At the end of the battle, the Mounties and their militia allies lost 12 men and had 11 more wounded. The Métis, on the other hand, lost only five. Only through the intervention of Louis Riel did the Canadian forces manage to escape total destruction.

The rebellion was short-lived and the Métis and their Indian allies were defeated by a large Canadian military force and the North-West Mounted Police.

In Alberta, Blackfoot Chief Crowfoot rejected an invitation from the Cree to join their rebellion. He remained loyal to the North-West Mounted Police.

Religious Suppression:

In 1884, Parliament outlawed both the potlatch of the Northwest Coast peoples and the Sun Dance of the Plains tribes. The North-West Mounted Police were in charge of enforcing the ban against the Sun Dance.

In 1889, North-West Mounted Police urged the Department of Indian Affairs to define which dances, if any, that Indians would be allowed to participate in. The police would then be able to enforce these laws. After visiting the Kainai Sundance, Sam Steele, the Superintendent of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, wrote to his superiors asking them to discourage the ceremony.

Changes:

In 1904, King Edward VII conferred the title Royal upon the North-West Mounted Police. In 1920, their jurisdiction was extended throughout the entire nation and they became the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.