Non-Indians first encountered the Makah in 1788 when the British sloop Princess Royal anchored at the Makah village of Classet on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. The Makah, who occupy the western-most part of what is now the lower forty-eight states of the United States, had lived in this territory for thousands of years. Unlike the other Indian nations of coastal Washington and the Puget Sound area, the Makah are not a Salish-speaking group, but are instead the southern-most members of the Wakashan language family. Linguistically, the Makah are most closely related to the Nootka (Nuu-cha-nulth) of British Columbia.

Two years later, the Spanish explorer Manual Quimper traded with the Makah under chief Tutusi at Neah Bay. The following year, the Spanish explorer Francisco de Liza visited the Makah in Neah Bay and traded 33 sheets of copper for 20 small boys and girls. Slavery was common among the tribe of the Pacific Northwest long before European contact. Among the Makah, slaves were captured in warfare, or sometimes they were purchased from other tribes who had acquired them by capture.

In 1792, the Spanish returned with the intent of establishing a permanent colony on Makah territory on the Olympic Peninsula. Under the Doctrine of Discovery, the Spanish, as a Christian nation, felt that they had legal, moral, and religious rights in claiming Indian land. The colonists of Nunez Gaona came to describe the Makah as warlike, thievish, and treacherous. As a result, they soon abandoned the colony. José Cardero, the Spanish artist with the colony, painted the portrait of Chief Tatoosh and his two wives.

In 1828, Captain Henry Kellet landed at a Makah village for fresh water. He met Chief Dee-ah. Kellet was unable to pronounce the name correctly and recorded the site as Neah Bay.

In 1833, the Japanese ship Hojun-maru washed ashore near Cape Flattery. The ship had set sail more than a year before from the Japanese port of Toba with a cargo of rice and ceramics. A storm blew the ship off course. When the crippled junk made landfall, the Makah captured three Japanese sailors. The Hudson’s Bay Company bought the sailors from the Makah hoping to use them to open up trading with the Japanese.

For hundreds and perhaps thousands of years, ships from Japan and China had been riding the Kuroshio (Black) Current from Asia to North America. The Hojun-Maru was not the first crippled Asian ship to make the trip, nor would it be the last.

In 1849, Samuel Hancock established a trading post among the Makah at Neah Bay. The Makah had not requested the trading post and were unhappy about this intrusion on their land. They tried to make Hancock leave and threatened to kill him. Hancock threatened to contact the American government for military support and the Makah backed off their threats.

The non-Indians brought in more than manufactured trade goods, such as metal axes, guns, glass beads, and other items: they also brought with them epidemic diseases such as smallpox, measles, mumps, influenza, and more. These new diseases devastated Indian communities.

In the 1850s, smallpox ravaged the Makah, decimating their population. There was not a single epidemic, but several. Many elders died before they could transmit their cultural knowledge to others. In 1852, the Makah abandoned the village of Biheda because of smallpox. The residents moved to nearby Neah Bay.

Trading vessels from San Francisco carried smallpox to the coastal tribes of Washington and Oregon in 1853. An estimated 2,000-3,000 Indians died. One witness described the impact of the epidemic on the Makah at Neah Bay, Washington:

“The beach for a distance of eight miles was literally strewn with the dead bodies of these people.”

On the heels of the smallpox epidemic, and reeling from the deaths of so many tribal members, the Makah had to deal with another new disease: American greed. Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens imposed a series of treaties on the coastal Indian nations in which they gave up much of their homeland and moved out of the way of American settlement.

The Americans concluded the Treaty of Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula in 1855. The Makah agreed to the establishment of a reservation at Neah Bay. None of the five main Makah villages were included within the new reservation. While the Makah had been successful fishing people for thousands of years, the United States wanted them to become farmers on land which is not suited for agriculture.

As in other treaty councils, Stevens told the Makah to select a single man to serve as their supreme chief even though this had never been their traditional way. When they declined to do so, he simply appointed Tse-kow-wootl, an Ozette, as supreme chief.

The Makah, whose orientation was toward the sea, were willing to sign the treaty as long as it allowed them to continue to venture out onto the Pacific Ocean to fish and hunt whales so that they could support their people. The treaty called for the Makah to be paid $30,000 in goods.

In understanding the treaty, it must be kept in mind that the Makah had been devastated by smallpox and many of their traditional leaders were dead. Many of those who signed the treaty were not the traditional leaders.

Shown above is the longhouse in front of the Makah Cultural and Research Center.

The figures shown above are in front of the Makah Cultural and Research Center.

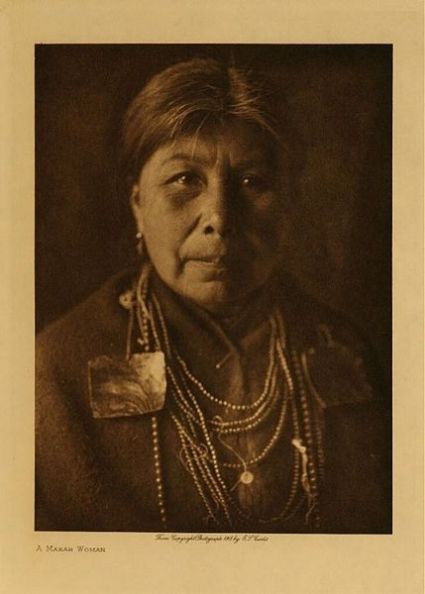

Shown above is a photograph of a Makah woman by Edward Curtis.

Leave a Reply