President Benjamin Harrison and Indian Policy

In 1889 Benjamin Harrison, an attorney, Presbyterian church leader, and Civil War Brigadier General, was elected President of the United States. Harrison, a Republican, defeated incumbent President Grover Cleveland. In his brief inaugural address, Harrison credited the nation’s growth to the influences of education and religion (meaning Christianity). For his cabinet appointments, Harrison considered three important criteria: (1) Civil War service, (2) membership in the Presbyterian Church, and (3) Indiana citizenship.

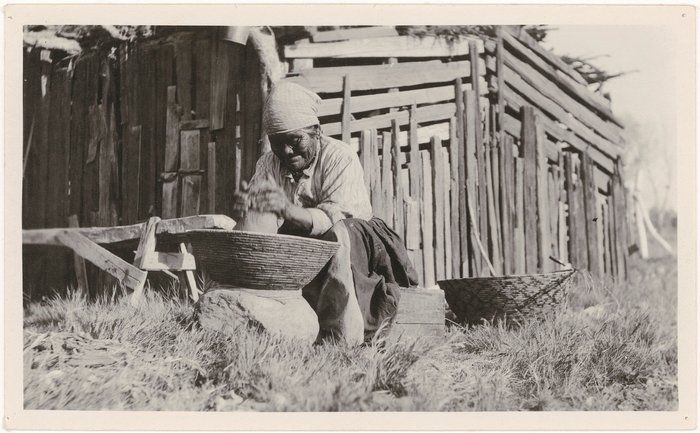

With regard to Indian affairs, Harrison believed that Indians, like the other immigrants to the United States, should be fully assimilated into American society. Assimilation, of course, required Indians to speak English, to be Christian, to dress in non-Indian clothing, to acquire a notion of greed so that they would acquire private property, and to get rid of reservations and tribal governments. He believed that the Allotment Act (also known as the Dawes) act would help Indians into civilization by divesting them of their reservations and communally held land.

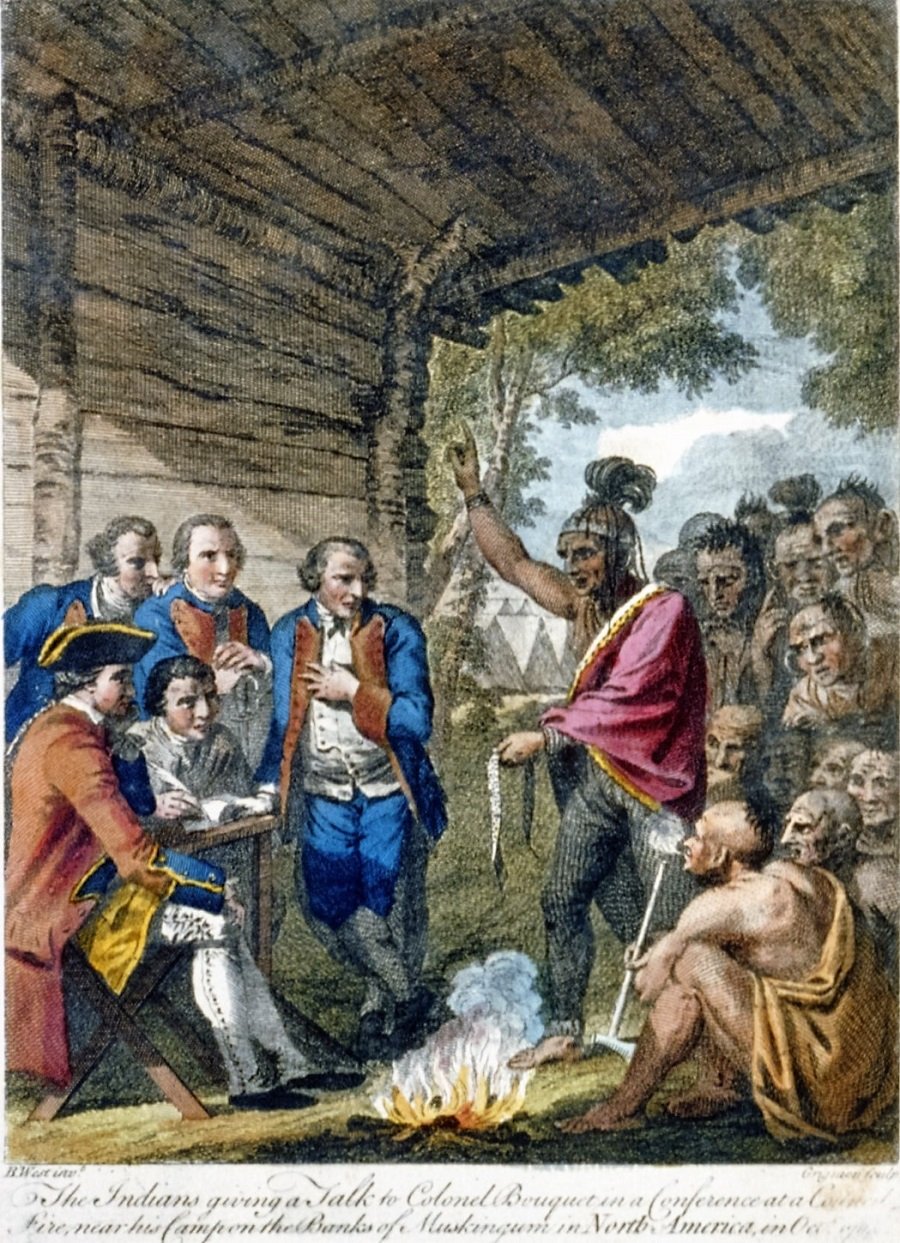

Like other Presidents, Harrison met with delegations of Indians. In 1892, Washo leader Captain Jim and his interpreter Dick Bender traveled to Washington where they met with Nevada and California senators and congressional representatives and President Benjamin Harrison. They were promised $1,000 for the immediate relief of the old and the infirm, but the money was never received.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs was the person in American government who had direct responsibility for Indian affairs. The position, which was under the Secretary of the Interior, was a political appointment. For his Commissioner of Indian Affairs, President Harrison appointed Thomas Jefferson Morgan. Like most of his predecessors, Morgan had no experience in Indian affairs, little contact with actual Indians, and no understanding of Indian cultures. He was, however, a Baptist minister and an educator with a fervent belief that Christianity held the solution to the “Indian problem.”

Morgan, who had served as an officer under Harrison in the Civil War, had contacted his old commander after Harrison won the Presidency asking to be appointed as Commissioner of Education. Instead, Harrison offered him the position of Commissioner of Indian Affairs, which Morgan accepted.

Shortly after becoming Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Morgan announced: “When President Harrison tendered me the Indian Bureau, he said I wish you to administer it in such a way as will satisfy the Christian philanthropic sentiment of the country. That is the only charge I received from him.”

In his 1889 annual report, Indian Commissioner Thomas J. Morgan indicated that tribal relations should be broken up; that Indian socialism be destroyed; and English be universally adopted. He writes: “The Indians must conform to ‘the white man’s ways,’ peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must.”

In 1890, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered traders to stop carrying playing cards. This was an effort to discourage gambling on the reservations.

Civil Service:

Four groups of Indian Service employees – physicians, school superintendents and assistant superintendents, school-teachers, and matrons – were placed under Civil Service Classifications in 1891. One of the members of the Civil Service Commission, Theodore Roosevelt, advocated that Civil Service rules be modified so that Indians could be given preference for these positions.

The following year, Civil Service Rules were extended to cover superintendents and teachers in the Indian Service. School Superintendent Edwin Chalcraft explained: “Prior to this time, Indian Agents made all those appointments, but from this date they were made by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs from names submitted to him by the Civil Service Committee in Washington, D.C. These rules prohibited the dismissal of employees for political or religious beliefs, but the Appointing Officer in Washington, D.C., could remove an employee for any other cause without giving him reason for doing so.”

Census:

The 1890 Census formally enumerated all of the Indians in the country. According to the Census, there were a total of 248,253 Indians in the United States: 58,806 were “Indians taxed” and 189,447 were “Indians not taxed.”

With regard to the difficulties in counting Indians, the Census Bureau reported: “Enumeration would be likely to pass by many who had been identified all their lives with the localities where found, and who lived like the adjacent whites without any inquiry as to their race, entering them as native born white.”

Wovoka’s Ghost Dance:

As a Christian nation, the policy of the United States was to require Indians to convert to Christianity and to actively suppress all Native religions. During the Harrison administration, religious intolerance climaxed with the teachings of a Paiute prophet named Wovoka in Nevada. In 1889, Wovoka died during an eclipse. He then returned to life with a message and a dance for his people. This was the birth of a Native American religious movement called the Ghost Dance by non-Indians.

Wovoka’s new religion spread from Nevada to Indian reservations in Idaho, Montana, South Dakota, and Indian Territory. Christian missionaries, Indian agents, the military, and politicians opposed the new religion without understanding anything about it. Inspired by newspaper reports written by reporters who never talked to any of the followers of the new religion, there were calls to suppress it. On several reservations Indians who participated in or advocated Wovoka’s religion were imprisoned and/or beaten. In some instances, Indians who were suspected of being involved with the Ghost Dance were murdered by ad hoc militia groups.

In December, 1890, Army troops were sent to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota to suppress the religion. The War Department issued a list of Indians who were to be arrested on sight. Their “crime” was simple: they had embraced a new religion, one which had not been approved by the United States government. At Wounded Knee, the Army surrounded a group of starving, freezing, and unarmed Indians who were flying white flags from their staffs. Using Hotchkiss machine guns the soldiers managed to kill 40 men and 200 women and children. Chasing fleeing women and shooting them was sport to the soldiers and the bodies of some of the women were found four to five miles from the slaughter site. Twenty-three of the soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their heroic action against unarmed Indians.

In testimony before Congress, General E. D. Scott strongly stressed that there was nothing to apologize for and suggested that the Indians were under a strange religious hallucination.

In his evaluation of the events surrounding the “battle” at Wounded Knee, Sioux physician Charles Eastman wrote: “I have tried to make it clear that there was no ‘Indian outbreak’ in 1890-1891, and that such trouble as we had may justly be charged to the dishonest politicians, who through unfit appointees first robbed the Indians, then bullied them, and finally in a panic called for troops to suppress them.”