The Caddo

A number of different Indian nations, usually grouped together as Caddo, lived in the territory that stretched from the Red River Valley in present-day Louisiana, to the Brazos River Valley in present-day Texas and Arkansas. For many centuries prior to the European invasion, the Caddoan peoples had made a living by farming. Like many other aboriginal farmers in North America, they raised corn (maize), beans, and squash.

The term “Caddo” originates from one particular tribe, the Kadohadacho who occupied the area around the Great Bend of the Red River in Texas. The term is also applied to a number of other tribes in the region who have a similar language and culture. Long before the European invasion, the Caddo were a group of about 25 related, but politically independent, theocratic chiefdoms.

At the time of the first contact with the French and Spanish explorers, the Caddo were associated in three or four loose confederations. The largest of these was the Hasinai, which the Spanish called Texas, who occupied a territory which includes the present-day Texas counties of Nacogdoches, Rusk, Cherokee, and Houston. The Kadohadacho, also called the Caddo proper, were located at the bend of the Red River in southwestern Arkansas and northeastern Texas. The Natchitoches occupied an area near the present-day Louisiana city which bears their name. The least known of these early confederacies is the Yatasi which soon after initial European contact divided into two groups which affiliated with other Caddoan confederacies.

The Cahinnio had a town on the upper Ouchita River. They are also called the Tula Indians in some sources. They eventually became a part of the Kadohadacho.

The Adai lived near present-day Robeline, Louisiana. Their Caddoan dialect is different from the other tribes.

The Eyeish lived near present-day San Augustine, Texas. Early writers often referred to these Indians as “barbarous”.

The Caddo first encountered Europeans in 1541 when the Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto crossed the Mississippi River. De Soto died in 1542 and his body was wrapped in a blanket weighted with sand and thrown into the Mississippi River. His expedition left a legacy of the torture, mutilation, and killing of hundreds of native peoples. Following de Soto’s death, Luis de Moscoso de Alvarado led the Spanish west into Caddo country.

In 1682, the French under Rene Cavalier de la Salle established a trading relationship with the Caddo. By this time, the Caddo had acquired horses by trade with friendly tribes who had been in contact with the Spanish settlements in New Mexico. According to Caddo oral tradition, a Caddo hunter and his family were the first to sight the bedraggled group. The hunter provided the French with some meat and invited them to his village. The French party stayed with the Caddo for three or four days, bartering for horses and supplies.

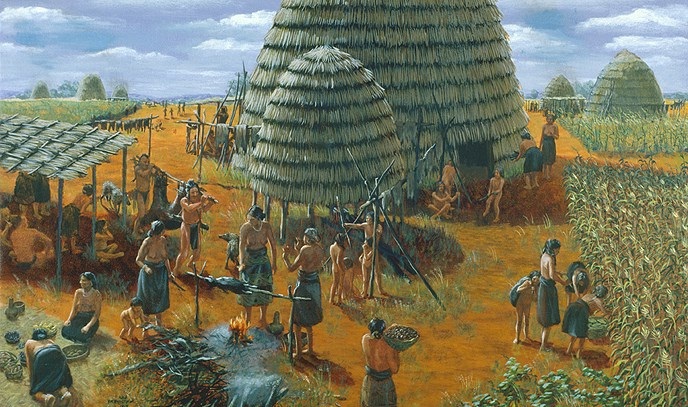

Father Anastasius, who was with La Salle, described the Caddo town as “one of the largest and most populous that I have seen in America. It is at least twenty leagues long, not that this is evenly inhabited, but in hamlets of ten or twelve cabins, forming cantons, each with a different name.”

He also described their “cabins” as being 40-50 feet high, in the shape of beehives.

Upon leaving the Caddo, four of La Salle’s men decided that Indian life more appealing than exploring and returned to the village. Over the next couple of centuries, it would be fairly common for Europeans to desert their own cultures and live among Indian nations.

In 1690, the French explorer Henri de Tonti set out to recover the Frenchmen from La Salle’s party who remained with the Caddo. He made contact with the Quapaw on the Upper Arkansas River and was given two Kadohadacho women to take along with him to Caddo country.

In what is now Texas, he made contact with three Caddo villages: Nachitoches, Ouasita, and Capiché. Here he was provided with guides to take him farther into Caddo country. He then went to the villages of Yatachés, Nadas, and Choye. He asked the chiefs for guides, but they were reluctant to provide him with any. Finally, he made it to Cadadoquis where he met with the woman who governed the Caddo nation. There is no indication that the “missing” Frenchmen were “recovered.”

In 1690, both French and Spanish accounts of the Caddo describe them as having numerous villages with large populations. Like their Mississippian cultural ancestors, they constructed large earthen pyramids (usually called mounds) and placed temples on top of them. By 1691, however, smallpox inadvertently introduced by the Europeans struck the Caddo killing about half of their population.

Many Caddo worked as trading partners with the French, often acting as intermediaries between the French and other tribes. In 1763, however, the French domination of Caddo territory was lost to the Spanish and the Caddo lost their trading partners. The Spanish restricted trade.

In 1801, the Caddo found that their right to govern had been sold to the United States and the United States was not friendly with Indians. The Caddo ceded their land to the United States and moved to Texas where they established the village of Sha’chadinnih. In 1822, the newly formed Mexican government offered a treaty to the Caddo in Texas. Chief Dehahuit indicated that he had no trouble swearing allegiance to the Mexicans, but he could not accept the treaty provisions which required the acceptance of the Catholic faith. According to Dehahuit, he cannot sign this treaty: “to accept the Catholic Religion and exclude all others, because one cannot speak their opinions for a people, especially concerning their Religions.”

When Texas joined the United States in 1845, the Caddo were no longer welcome in Texas. Texas did not recognize any Indian claims to land ownership and Texans were free to claim Indian land. Caddo chief José María said: “That now there was a line below which the Indians were not allowed to go; but the white people came above it, marked trees, surveyed lands in their hunting grounds, and near their villages, and soon they would claim the lands; if the Indians went below they were threatened with death; that this was not just.”

With the annexation of Texas, the United States assumed responsibility for Indians and the state of Texas reserves all rights to public lands. According to Caddo cultural representative Cecile Elkins Carter, in her book Caddo Indians: Where We Come From: “Texas would be for Texans, and the United States would have to remove Indians as quickly as Texans were ready to move onto Indian lands.”

In 1859, the United States resettled them on a reservation in Indian Territory which would later become a part of Oklahoma. The new reservation included the Caddo, Anadarko, Ioni, Waco, Tonkawa, and Tawakoni.