The Hoko River Complex

The Hoko River originates in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains (Washington State) and flows for about 25 miles to the Pacific Ocean. It flows into the Strait of Juan de Fuca about 16 miles east of the Makah town of Neah Bay. By 3,000 years ago, the Makah were using the area around the mouth of the river for a wide range of sea, river, and forest resources. The Hoko River Archaeological Complex is composed of three site areas: (1) a riverbank wet site, (2) dry campsites adjacent to the wet site, and (3) a rock shelter at the mouth of the river.

The Hoko River sites first came to the attention of archaeologists in 1967 when people reported to Washington State University that they were finding artifacts in the area. An archaeological survey found that a large site ran some 600 feet along the river and that much of the site had already slumped into the river. Full-scale investigation, however, did not begin until 1977. Initial financial support was provided by the Makah Tribal Council and the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust. Some additional support was provided by Jean Auel, the author of a series of archaeological-based novels.

Wet sites provide some interesting challenges for archaeologists. Writing in the Handbook of North American Indians, Gary Wessen from the Makah Cultural and Research Center describes the Hoko River wet site:“Most of the wet site is situated within the range of tidal fluctuations, and much of it can only be examined during low tides.”

Ruth Kirk and Richard Daugherty, in their book Archaeology in Washington, describe the problems in working with the wet site: “Excavation entailed pumping water from the river and spraying it out through garden hoses to gently wash artifacts free from the riverbank mud that held them. Conventional troweling, no matter how careful, might damage a wooden or fiber artifact before it could be noticed.”

Wet sites, however, have an advantage as the artifacts have stayed wet for millennia and have been spared from decay. Once they are excavated from the site, they must remain wet. For preservation and analysis, the artifacts are bathed in polyethylene glycol which soaks into the waterlogged tissue, replacing the water with wax.

The excavation at the Hoko River Wet Site yielded many fiber artifacts, including baskets, hat, mats, nets, and cordage. Nearly 70% of the material from the site was cordage. Some of the baskets uncovered at the site had been coarsely woven which allowed water to drain out. According to the Makah elders from Neah Bay, these baskets would have been used for packing salmon from fishing weirs upriver to drying racks at the camp at the river mouth.

One of the other interesting finds was a fishnet with two-inch mesh. This artifact was uncovered in deposits which dated to 3,200 years ago. Ruth Kirk and Richard Daugherty report: “Scanning electron microscope examination of cell structure identified its fiber as split spruce root or bough, most likely bough, which is stronger than root and absorbs water less readily.”

Ethnographies of Northwest Coast Indian nations, such as the Makah, report that one of the symbols of nobility, of high-class status, was a woven hat with a knob on top. At the wet site, five of these hats were recovered, which suggests that social stratification in this area was much older than previously thought.

The wet site also yielded a number examples of tule mats which were used for many different things including mattresses, canoe cushions, partitions within the long houses, and so on. As a part of the archaeological efforts to understand the past, Makah tribal elders instructed the archaeological field school students in making tule mats. Ruth Kirk and Richard Daugherty report: “The goal of the early Hoko River people must have been to make high-quality, long-lasting mats, and therefore, even an experienced mat-maker must have needed three or four days to gather materials for a single mat, prepare them, make the string, and do the sewing.”

Tule mats were used to cover the sides of temporary shelters. The postholes found at the dry site were used to estimate the size of the temporary shelters and it was determined that six to eight mats would have been needed for these shelters. Each mat would have been about four feet by eight feet.

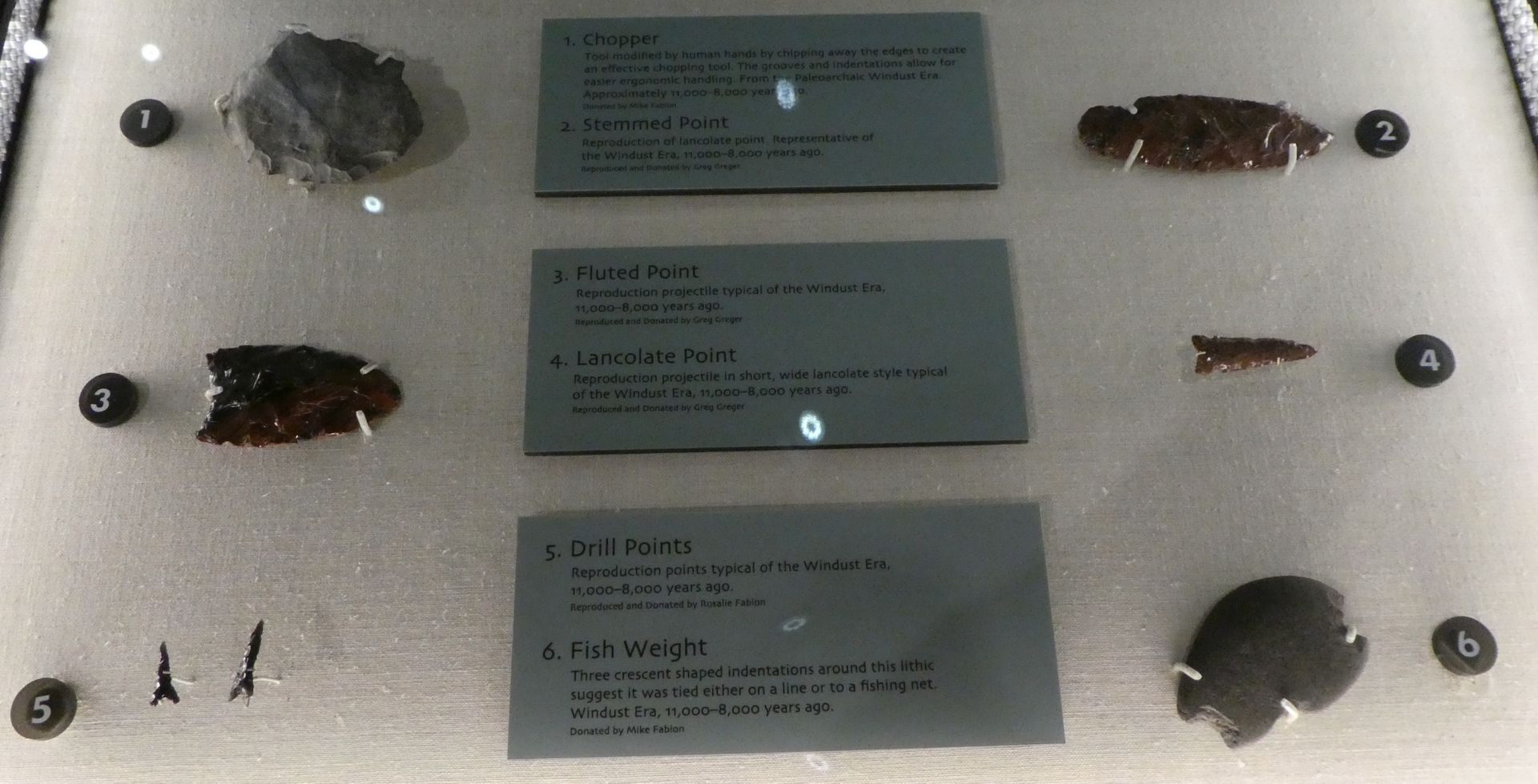

At many sites along the Northwest Coast archaeologists have found small stone blades known as microliths. It was assumed that these microliths had been hafted in some fashion. At the wet site, the archaeologists found hafted knives in which thumbnail-size stone flakes had been placed in between five-inch splints of red cedar and then bound with spruce root and wild cherry bark. Working with the Makah elders, experimental archaeology showed that these knives were used in butchering fish.

At the dry campsite, archaeologists uncovered the bones of rockfish, cod, dogfish, flounder, halibut, salmon, and other fish. The deep-sea species are evidence of off-shore fishing. This means that the people who used the Hoko River sites had watercraft. In addition to fish bones, the archaeologists also found several hundred wooden fishing hooks. These fishhooks date from 1,700 to 3,000 years old and show little change through time.

The dry campsites, located in the forested area back from the river, are composed of three sites dating to 3,400 years ago, 3,100 years ago, and 1,700 years ago. Stone debris shows that some toolmaking was done here. There are also stone-lined storage pits.

The rock shelter at the mouth of the river dates to about 1,000 years ago and shows evidence of seasonal use. The rock shelter had been originally formed through river and wave action and over time had been uplifted by 30 feet, which made it usable for human occupation. Ruth Kirk and Richard Daugherty report: “The placement of the hearths suggested that people lived in the northern part of the rock shelter, where prevailing winds would tend to clear out smoke or blow it to fish-drying racks set up in the southern part of the cave.”

Sea mammal bones found at this site include fur seal (69% of the sea mammal bones), elephant seal, porpoise, and whale.