William Weatherford, Red Stick Leader

The designation “Creek” is a European concept which emerged during the eighteenth century to designate the Indian people who were living along the creeks and rivers in Alabama, Georgia, and northern Florida. While these people have a cultural continuity which reaches back to the mound building cultures of this area, the concept of a Creek “Nation” or “Confederacy” is something which did not emerge until after the European invasion. In reality, the Creek were several autonomous groups. The aboriginal homeland of the Kosatis had been in the Tennessee River Valley, but in the late seventeenth century, they fled their homeland and joined the Creek confederacy in Alabama to gain protection against Indian slavers.

The Kosatis, like other Indian nations in the Southeast were matrilineal. This meant that each person was born into the mother’s clan. Thus in 1781 (some sources list 1780), William Weatherford, also known as Red Eagle, was born into the Creek Wind Clan. His mother was Sehoy III, the half-sister to Creek leader Alexander McGillivray. His father was Charles Weatherford, a trader who is described as being “of partial Indian descent.” When the Creek National Council voted in 1798 to expel traders, Charles Weatherford was exempt due to the influence of the Wind Clan. However, by 1799 he had left his family.

Divorce was common among the Creeks and since clan relationships were more important than those of the nuclear family, it was rarely traumatic to children. Sehoy was a successful and wealthy businesswoman who owned about 30 slaves. With regard to her son, Christina Snyder, in her book Slavery in Indian Country, writes: “William excelled at the Creek masculine arts of hunting and stickball, and his reputation as an eloquent speaker may have been what prompted his contemporaries to dub him ‘Truth Teller.’”

In 1813 a civil war broke out within the Creek Confederacy. There were two factions among the Creeks: the Red Sticks (called this because their war clubs were painted red), led by Peter McQueen and William Weatherford, who wanted war with the Americans, and the White Sticks, led by Big Warrior, who wanted peace.

A number of Creek spiritual leaders, influenced by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother The Prophet, preached a nativistic doctrine. These leaders include Hilis Hadjo (Josiah Francis), Cusseta Tustunnuggee (High-Head Jim), and Paddy Walsh. These prophets sought to restore a time when the produce of a woman’s farm and the meat from a man’s hunt sustained every Creek household. Christina Snyder writes: “Despite his upbringing, William likely believed, as other Red Sticks did, that the Creek Nation’s turn toward plantation agriculture, political centralization, and racial slavery was misguided.”

William Weatherford (Red Eagle) and his warriors attacked Fort Mims on the Alabama River. Weatherford’s force has been estimated at 1,000 warriors. Here the Red Sticks killed about 400 non-Indians (some sources indicate that they killed as many as 500) and freed the slaves. Consequently, many runaway black slaves joined the Red Sticks. However, many Creek warriors were killed and wounded in the battle. The Creek prophet Paddy Walsh was blamed, for he had failed to make the warriors invincible as he had promised.

At the Battle of the Holy Ground, American troops attacked the Red Stick village of Econochaca on the Alabama River. Pursued by the Americans, Weatherford, riding his grey horse Arrow, charged off a high bluff and landed safely in the river some 20 feet below.

In response to the attack on Fort Mims, Tennessee, Georgia, and Mississippi raised armies to invade Creek territory. In 1814, at the battle of Horseshoe Bend, General Andrew Jackson’s troops (which included Cherokee as well as his Tennesseans) defeated the Creek Red Sticks, killing 800 Creek warriors. As a result of this defeat, the Creek were forced to sign a treaty in which both the peaceful White Sticks and the militant Red Sticks gave up 23 million acres of land. While White Stick leader Big Warrior had fought with the Americans, Jackson threatened him with handcuffs unless he signed the treaty. While the friendly Creek were told that the United States would remember their fidelity, within a few months the Americans no longer made any distinction between the “friendly” Creek and the Red Sticks.

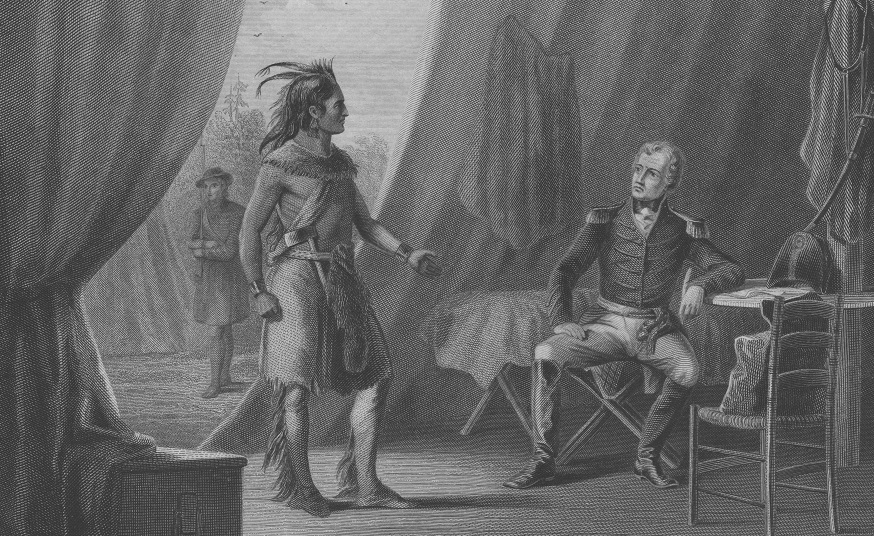

William Weatherford (Red Eagle) had not been at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. General Jackson hunted for Weatherford for weeks in vain, but was unable to find him. Later, in Jackson’s own camp, surrounded by armed soldiers who had vowed to capture William Weatherford and put him in chains, General Jackson was approached by a tall Indian who simply said in fluent English: “I am Bill Weatherford.” There was no accurate recording of the General’s surprised response. Weatherford seemed to have simply materialized in the midst of an enemy camp. He had somehow walked past the supposedly alert sentries, through the throngs of soldiers, and appeared at the General’s side.

The two men, accompanied by General Jackson’s aide who recorded the conversation, went in the General’s tent. Weatherford told General Jackson: “I can oppose you no longer. I have done you much injury. I should have done you more…my warriors are killed…I am in your power. Dispose of me as you please.” General Jackson replied: “You are not in my power. I had ordered you brought to me in chains….But you have come of your own accord.”

The two men then shared a glass of brandy. General Jackson promised to help the Creek women and children and Weatherford promised to try to preserve the peace. Weatherford then left the tent, walked by the soldiers, and disappeared into the brush.

Following the Red Stick War, William Weatherford, with the help of his Wind Clan relatives, established a large plantation in southern Alabama and assumed the lifestyle of a wealthy planter. During this time, he would often stop to eat at a wayside tavern run by Mrs. William Boyles. One evening four strangers entered the tavern and sat at Weatherford’s table. Not knowing who he was, the strangers began talking about wanting to find that “bloody savage, Billy Weatherford.” They were probably more than a little surprised when the man at their table said: “Some of you gentlemen expressed a wish while at dinner to meet Billy Weatherford. Gentlemen, I am Billy Weatherford, at your service!” One of the strangers timidly shook his hand while the others simply looked frightened.

William Weatherford died in 1824. Christina Synder writes: “William Weatherford was a planter and slaveholder, and by right of matrilineal descent reckoning, he was also unequivocally a Creek Indian who hunted, warred, and traded as his ancestors had for centuries. Without contradiction, he lived as both warrior Truth Teller and gentlemen planter Billy Weatherford.”