California’s War On Indians, 1850 to 1851

In 1850 California was admitted to the United States as its 31st state. As with some other states, Native Americans were not seen as desirable inhabitants of the state. For the first decade of its existence, the State of California carried on a series of privatized wars of extermination against the Native American population. California’s first governor, Peter Burnett, openly called for the extermination of Indian tribes.

In 1850, California passed an Act for the Government and Protection of Indians. The Act stated that while both non-Indians and Indians may take complaints before a justice of the peace, that “in no case shall a white man be convicted on any offense upon the testimony of an Indian.”

In other words, if a non-Indian were to commit a crime, such as murder, rape, or theft, and the only witnesses were Indians, then no conviction would be possible. The act also curtailed Indian land rights.

The Act also allowed non-Indians to obtain Indian children by going before a justice of the peace and securing a certificate which allowed them to have the care, custody, control, and earnings of these children. The illegal sale of Indian children became common and during the next 13 years an estimated 20,000 California Indian children were placed in bondage.

James Parins, in his biography John Rollin Ridge: His Life and Works, explains another ramification of the law: “if an Indian was arrested on charges of drunkenness and could not pay his fine, a white rancher could pay the amount levied by the court and then set the prisoner to work until the debt was paid. The Indian had no voice in setting the terms of this transaction, those details being left to the judge and the rancher.”

The law empowered non-Indians to arrest Indian adults for loitering and other offenses and then the captives were sold to the highest bidder. Indians had to work for four months without compensation. In other words, this Act opened up the door to involuntary servitude of Indians, a form of slavery in a non-slave state.

In the San Joaquin Valley and in the foothills of California’s Sierra Nevadas, the Miwok and the Yokut, under the leadership of Tenaya, began a war against the miners and settlers who had entered their territory as the result of the Gold Rush. The warriors attacked prospectors and burned James Savage’s trading posts. The conflict was known as the Mariposa Indian War.

In 1850, the governor launched a war against Indians who were accused of stealing stock near the mines in the central part of the state. A state militia of 200 men was called up. The militia encountered about 150-200 Miwok in a steep canyon. While they killed three Indians, the militia was forced to retreat. In a second battle which lasted for five hours, the militia killed 15 Indians. Two of the militia were killed. The one-month campaign in El Dorado County cost more than $100,000. For the militia commanders, the war was very lucrative while it was expensive for the California taxpayers.

In 1850, the American military began a campaign against the Pomo at Clear Lake in revenge for the killing of two non-Indians the previous year. The Pomo leader Ge-Wi-Lih met the Americans with his hands up to indicate peace, but was shot. The soldiers shot women and children. They also bayoneted babies and burned one man alive. An estimated 135 Indians were killed.

In 1850, the first American gold miners reached Hupa territory. When the Hupa offered hospitality to the miners, the miners asked them to leave their camp. While some shots were exchanged, the Hupa offered peace. Byron Nelson, in his book Our Home Forever: A Hupa Tribal History, explains: “Knowing that a pitched battle in their homeland would involve many innocent people, the Hupa hoped to prevent disastrous violence. Instead of taking revenge, they came to restore harmony and offer food to the miners.”

In 1850, the Anglos in the newly created Shasta County gave a friendship feast for the Wintu. The food, however, was poisoned and 100 Wintu died.

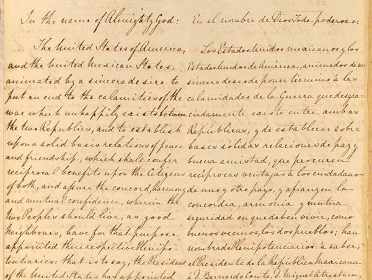

Under the Constitution of the United States, Indian tribes are sovereign nations and during the nineteenth century the federal government negotiated treaties with Indian tribes as a way of obtaining their land. In 1851, the United States negotiated 18 treaties with California Indian nations which were supposed to secure legal title to public land and guarantee reserved lands for Indians. The Indian commissioners explained to the non-Indian residents of the state that the government had two options: to exterminate the Indians or to “domesticate” them. They argued that “domesticating” them was more practical.

None of the commissioners who arranged the California treaties knew anything about California Indians. According to anthropologist Robert Heizer in the Handbook of North American Indians: “Their procedure was to travel about until they could collect enough natives, meet with them, and effect the treaty explanation and signing. One wonders how clearly many Indians understood what the whole matter was about.”

In the treaty council with the Karok, Yurok, and Hupa, the government promised to give the Indians a protected reservation and gifts if they would agree to wear clothes, live in houses, and become farmers. The government was apparently unaware that these groups had been living in plank houses for millennia.

Signing the treaty for the Hupa are what the Americans call the “head chief” and “under chiefs.” None of these men had formal authority over all of the villages. They were, however, men of great influence.

While these treaties were signed by both Indian and U.S. government leaders, they were not debated in the Senate, thus did not appear in the Congressional Record. For more than 50 years the California treaties were somehow lost or hidden. The ratification of the treaties was opposed by the California legislature and there were rumors that the state representatives managed to have the treaties hidden in the archives of the Government Room in the Capital.

Ensuing legislation deprived California Indians of the rights to their land. The impact on the Indians is immense. Historian Herman Viola, in his book After Columbus: The Smithsonian Chronology of the North American Indians, reports: “Bereft of homes, unprotected by treaties, the Indians became wanderers, hounded and persecuted by whites.”

Anthropologist Omer Steward writes: “The failure to ratify the treaties left the federal government without explicit legal obligation toward the Indians of California.” During the next 50 years, California Indian population will decrease by 80%.”

In 1851, the Americans destroyed a natural bridge crossing Clear Creek in an effort to keep the Wintu on the western side of the creek. Miners then burned the Wintu council house in the town of Old Shasta and massacred about 300 people. Following the massacre, the Wintu consented to the “Cottonwood Treaty” which gave them about 35 square miles of land.

In 1851, the Cahuilla, Quechan, and Cocopa under the leadership of Antonio Garra, Jr. in San Diego County revolted against the American federal, state, and local governments. The cause of the rebellion was a state tax imposed on Indian property. Garra attempted to put together a confederacy of several tribes, but was captured by a rival Cahuilla band and turned over to the Americans. He was tried in a paramilitary court, found guilty, and shot.

In 1851, the Modoc raided ranches in the Shasta Valley for horses and cattle. In response, the ranchers organized a party of volunteers to recover the livestock and kill the Modoc. The volunteers killed 20 Modoc men and captured 30 women and children.

In 1851, American settlers burned an Indian village on Mill Creek (possibly a Yahi village) in retaliation for the supposed theft of a cow.

In 1851, the United States paid out more than $1 million in bounties for Indian scalps.