The Cherokee Trail of Tears

By the first part of the nineteenth century, many non-Indians in the United States, particularly in the southern states, felt strongly that there should be no Indians in the United States. They felt that all Indians should be forced to move from their ancestral homelands to new “reservations” located west of the Mississippi River. In general, the concept of removal stemmed from two concerns of the Southern non-Indians: economics and race. Southerners lusted for the farm lands held by Indians and Indians were felt to be racially inferior.

The primary argument in favor of Indian removal claimed that European Christian farmers could make more efficient use of the land than the Indian heathen hunters. This argument conveniently ignored the fact that Indians were efficient farmers and had been farming their land for many centuries. Historian David La Vere, in his book Contrary Neighbors: Southern Plains and Removed Indians in Indian Territory, writes: “It mattered little that the Southeastern Indians had long been successful agriculturalists; in the government’s eyes they were still ‘savages’ because they did not farm the ‘correct’ way, as women still controlled the fields and farming.”

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. The Act passed 28 to 19 in the Senate and 102 to 97 in the House. In making the case for Indian removal, Lewis Cass, the Secretary of War, wrote in the North American Review: “A barbarous people, depending for subsistence upon the scanty and precarious supplies furnished by the chase, cannot live in contact with a civilized community.”

In 1838, General Winfield Scott began preparation for the removal of the Cherokee. He explained to the Cherokee that there would be no escape: his troops were to gather up all Cherokee. If they attempted to hide in the forests or mountains, he told them that the troops would track them down. He drew up plans to gather the Cherokee in a few locations prior to sending them west. Brian Hicks, in his book Toward the Setting Sun: John Ross, the Cherokees, and the Trail of Tears, writes: “Soldiers were told to swarm Cherokee houses without warning, giving the Indians no time to put up a fight or even pack their belongings. Families would be taken at once and brought into one of several camps. The men must be polite and not use profanity.”

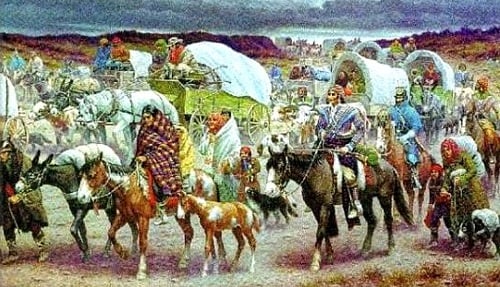

The United States Army rounded up the Cherokee who were living in Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, and Alabama. Mounted soldiers, using their bayonets as prods, herded the Cherokee like cattle. One of the soldier-interpreters for the Army wrote: “I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes and driven at bayonet point into stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and headed for the West.”

If there were no adults home when the soldiers came to the Cherokee farms, then the children were taken in the hopes that their parents would follow. The vacant farms were then occupied by non-Indians who took over the Cherokee houses, used Cherokee furniture, utensils, and tools, and harvested the crops which the Cherokee had planted and tended. They also robbed Cherokee graves, stealing the silver pendants and other valuables which had been buried with the dead. One non-Indian observer wrote: “The captors sometimes drove the people with whooping and hallowing, like cattle through rivers, allowing them no time even to take off their shoes and stockings.”

There were 3,000 regular soldiers and 4,000 citizen soldiers who assisted in the expulsion of the Cherokees. These soldiers often raped, robbed, and murdered the Cherokee. Some of the soldiers who were ordered to carry out the forced removal refused to do so. The Tennessee volunteers went home, saying that they would not dishonor Tennessee arms in this way. Many civilians who witnessed the treatment of the Cherokee signed petitions of protest.

The Cherokee were herded into animal corrals with no sanitary facilities. The stockades were so overcrowded that it was difficult to find room to sit down. They were not provided with adequate food and water. Brian Hicks writes: “These stockades were like fortresses, two hundred feet wide and five hundred feet long with walls between eight and sixteen feet high. There was a single gate. Inside each of these camps a few small cabins ringed a great field.”

The Cherokee were then force-marched some 1,500 miles to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River (now the state of Oklahoma.) During this march, 8,000 Cherokee died. The Cherokee call this episode in their long history Nunna daul Isunyi, which means “trail where we cried”. Others call it the Trail of Tears and often refer to it as the most disgraceful event in American history and as one more piece of evidence about the genocide which was attempted against American Indians.

The Cherokee were not at war with the United States. At this time, there was no American who could remember any unprovoked violence by the Cherokee. The Cherokee were known to be good neighbors and had adopted much of the European manner of living, including Christianity.

In Georgia, however, the press reported on the Cherokee removal with these words: “Georgia is, at length, rid of her red population, and this beautiful country will now be prosperous and happy.”

The Cherokee were not the first tribe that was moved in this fashion, nor were they the last. The Trail of Tears was not an event which suddenly happened: rather it was the culmination of more than 30 years of actions and attitudes. It was an expression of states’ rights; it was an expression of greed for land; it was a denial of Native American tribal sovereignty; and it was an expression of the government’s inability to understand Indian people. One of the important points of conflict was the government’s concern for individually owned land and the Indian view that land was not to be owned by the individual, but by the tribe.

We talk about the Trail of Tears and similar events so that others may not repeat the errors of the past. It is important that we remember and that we talk about this today. In many ways the political climate of the United States today is similar to that which led up to the Trail of Tears. Let us recall these things now so that we can say: “Never again!” Never again should the United States act in such a callous manner toward those who gave this country so much of its heritage.