The First Seminole War

During the nineteenth century the United States engaged in three wars with the Seminole Indians in Florida: 1816 to about 1824; 1835 to 1842; and 1855 to 1858.

Contrary to some popular opinions, there was no traditional overall governmental or political organization among the Seminole at this time. They tended to be politically organized around busk groups, each of which had its own medicine bundle on which the annual busk (green corn) ceremony was focused. Thus the Seminole military actions against the U.S. military did not have a single leader or coordinator.

Prelude to the First Seminole War:

The colonial administration of Florida was transferred from Spain to Britain in 1763. The Spanish and some of the Indians affiliated with them moved to Cuba. At this time, the British began to use the term Seminole in distinguishing the Indians of northern Florida from those in Georgia and Alabama.

In 1765, 50 Lower Creek chiefs met with the British governor of Florida on the banks of the St. Johns River west of St. Augustine. The chiefs performed a pipe ceremony and smoked with the two English representatives. Cowkeeper of the Alachua band did not participate in this meeting, and made it clear that the Lower Creeks did not speak for him. A month later, Cowkeeper and 60 of his people met personally with the governor and returned home as a “Great Medal Chief”. After this meeting, travelers, traders, and government officials increasingly referred to the Indians of North and Central Florida as Seminoles. Some people feel that this marks the birth of the Seminole nations.

Cowkeepers’s band had migrated south from the Oconee Creek area of South Georgia into Florida where they herded the wild cattle descended from the Spanish herds of the old La Chua Ranch. The earliest use of the term “Seminole” – a corruption of the Spanish term “cimarron” meaning “wild ones” – was in reference to this band.

In 1777, Seminole warriors led by Cowkeeper and Perryman joined with British troops on raids into Georgia.

In 1784, the British left the area and turned the governing of Florida back over to the Spanish. The British held a final conference with some Seminole leaders, including Kinache of Mikasuka, Five Bones of Coweta, and Long Warrior of Cuscowilla. The Seminole expressed their dismay at having the British leave. Cowkeeper told the English that he would kill all Spanish who tried to enter his land. When Cowkeeper died a short time later—he was estimated to be in his seventies—his dying words urged his people to continue fighting the Spanish. With the death of Cowkeeper, the leadership of the Alachua band passed to his nephew, King Payne. With regard to the death of Cowkeeper, historian Colin Calloway, in his book The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities, writes:

“Even though his dying words ostensibly urged his people to continue fighting the Spaniards, his death eased to some degree the transition from the British to the Spanish regime.”

As a preview to the Seminole Wars, the Georgia Militia and other volunteer groups invaded Spanish Florida on several occasions and engaged the Seminole militarily. The Georgian invasions centered around two closely interrelated concerns: (1) to acquire Florida for the United States, and (2) to capture escaped African slaves who had found refuge among the Seminole. It was not uncommon for escaped slaves to become a part of Seminole culture, marrying into the tribe and having children.

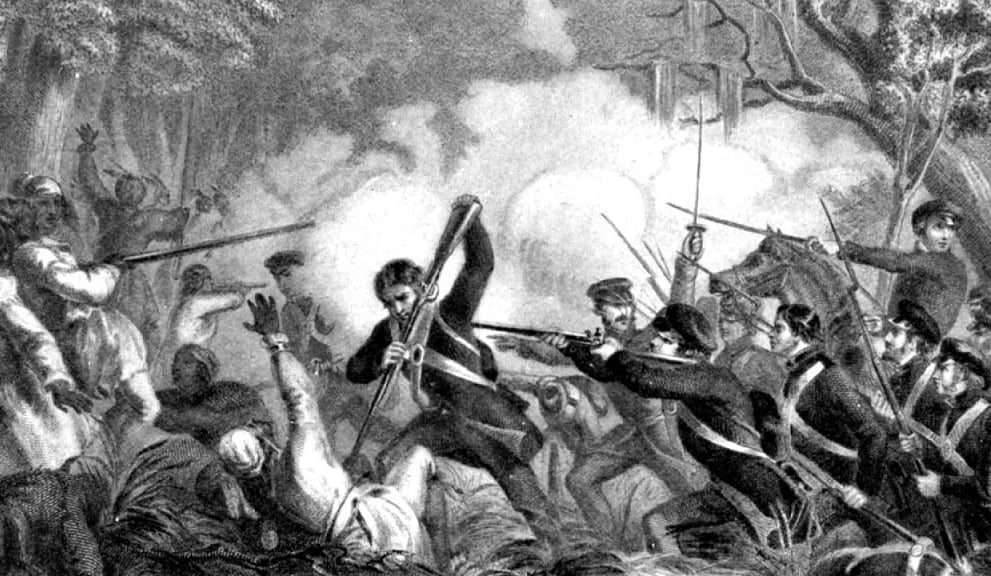

In 1811, the Patriot Army composed of 70 Georgians and nine Floridians invaded Florida to seize the territory. The army quickly occupied Fernandina and moved toward St. Augustine. However, the Seminole attacked the invaders and the plantation owners who supported them. The Seminole killed eight Americans and liberated a number of cattle and slaves from the American plantations.

In order to rescue the Patriot Army, the Georgia Militia sent in 177 men who fought three engagements with the Seminole. The Americans attacked Payne’s Town where they caught the Seminole by surprise. However, Seminole leaders King Payne (who was 80 years old at this time) and Bowlegs directed fire against the American attackers and drove them off.

In 1812, the Seminole village of Paynes Town was attacked by Georgia militia who were a part of the U.S.-inspired offensive to seize Florida from the Spanish. The Seminole wealth was in their cattle, which made tempting targets for Americans looking for booty and quick wealth. Archaeologist Brent Richards Weisman, in his book Unconquered People: Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee Indians, reports:

“The Seminole wealth on the hoof and their agricultural surpluses stored away in corn cribs and potato houses made tempting targets for groups of border ruffians.”

The Seminole, under the leadership King Payne, counter-attacked and drove the militia back. King Payne, however, was killed and his brother Bowlegs assumed leadership. Bowlegs had about 200 Seminole warriors and 40 African Americans and they waged a war to cut off the Patriots’ supply line.

In a three-week campaign, the Americans burned 386 Seminole houses and destroyed or consumed 1,500 to 2,000 bushels of Seminole corn. Twenty Seminole were killed and nine were captured. With the aid of Florida’s free black militia troops commanded by Lieutenant Juan Bautista Witten, the Seminole turn the tide of the war and the Patriots withdraw.

In 1815, the British withdrew their troops from Florida in accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Ghent which ended the War of 1812. However, when it became obvious that the Americans had no intention of honoring article 9 of the Treaty which specified that the Indians would not lose any land, the British left a large supply of arms and ammunition behind for the Indians to use.

First Seminole War:

The first Seminole War erupted in 1816 when the United States army, aided by Creek allies, invaded Spanish Florida. The rationale for the invasion centered around escaped slaves and Seminole raids. The war involved a series of raids and counterraids and culminated with General Andrew Jackson’s scorched earth campaign against the Seminole. As a result of this war, the United States acquired Florida from Spain.

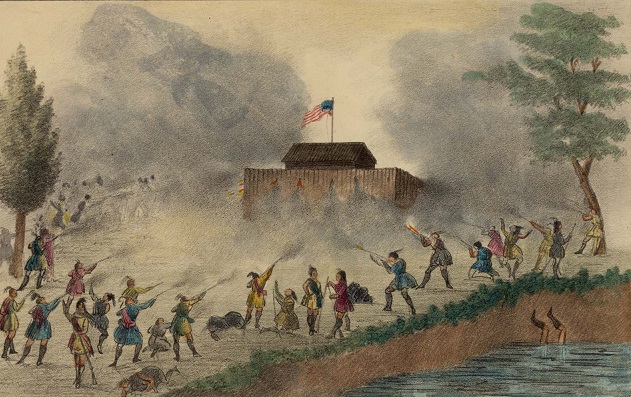

American soldiers together with 200 Creek warriors under Chief William McIntosh invaded Spanish territory in an attempt to capture blacks who were living among the Seminole. The 300 Seminole – including 30 Seminole men and 70 black men – took refuge in Fort Apalachicola. The fort was blown up by the Americans, killing 270 people. The survivors were taken to Georgia where they were enslaved. In revenge, other Seminole began a campaign of attacking American settlements along the Georgia-Florida border. This marked the beginning of what would later be called the First Seminole War.

In 1817, the United States demanded that Neamathla, a Red Stick Seminole leader, surrender some alleged murderers. When Neamathla refused, the army sent in a force of 250 men to attack his village. Five Seminoles—four men and one woman—were killed and the rest escaped into the swamp. In his book The Seminoles of Florida, historian James Covington reports:

“This episode marked the first action in what has come to be known as the First Seminole War.”

Neamathla’s band then joined forces with the Seminole under the leadership of Kinache.

In 1817, the Seminole attacked and killed a party of 40 Americans. In retaliation, American troops under the leadership of Andrew Jackson invaded Seminole erritory, burning homes, and capturing some slaves.

In 1818, American troops under Andrew Jackson and Creek warriors under William McIntosh invaded Spanish Florida and attacked the Seminole village of Chief Bowlegs on the Suwanee River. Jackson’s force outnumbered the Seminoles by at least ten to one, so the Indians simply directed some scattered shots toward the advancing soldiers and then fled to nearby lowlands. Although the Seminole escaped the attack, the Americans captured two Englishmen who had been living with the Seminole. The Englishmen were tried and hanged for aiding the Indians.

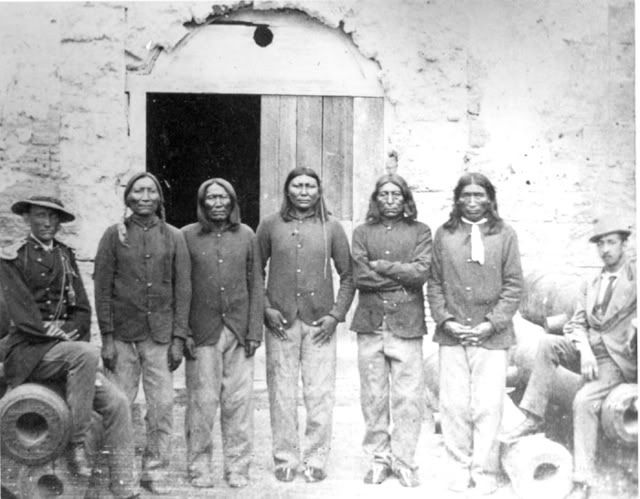

The army also captured a number of women and children, including Billy Powell (who would later be known as the warrior Osceola).

In 1819, Spain sold Florida to the United States. The United States promised to honor the rights of the Indians. Historian Louise Welsh, in an article in Chronicles of Oklahoma, notes that the Seminoles

“certainly had no reason to welcome the substitution of the United States control for the weak and distant authority of a Spanish sovereign.”

Two years later the United States formally took possession of the territory, which included an estimated 5,000 Seminole. The Americans immediately began making plans to relocate the Seminole who were living near the American settlements. The American governor viewed the area between the Suwanee River and Alachua, the area in which most of the Seminole lived, as the richest and most valuable in the territory. The Americans assumed that this land should be given to American settlers for development and the Seminole should be moved to Alabama or to west of the Mississippi River. The Americans did not recognize any Seminole rights to land ownership. According to historian John Mahon, writing in the Handbook of North American Indians:

“As far as the new owner of the land was concerned the Seminoles were an unwelcome appendage to the soil, clearly without any right of permanent ownership in it.”

The United States decreed that Neamathla was the chief of the Seminoles in Florida. In actuality, Neamathla was an eneah, an advisor to the village chief. As a Hitchiti (one of the tribes considered to be Seminole by the Europeans), Neamathla was determined to retain his culture and economic way of life.

In 1823, the Seminoles signed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek. The terms of the treaty called for the Seminoles to give up all land claims in Florida except for a reservation to be designated for them by the government. In addition, all Seminoles were to move to the reservation where they were to be provided with tools, annuities, and rations. Historian Louise Welsh reports:

“Government officials had decided that the ideal solution to the Seminole problem was to remove them to the West or merge them with the Creeks. The Seminoles opposed both proposals so vigorously that they were removed to a reservation in the interior of the Florida peninsula below Tampa Bay.”

The Treaty also divided the Seminoles into two divisions: a northern group and a southern group.

In 1824, President James Monroe recommended that the Seminole either be removed from Florida or placed on a reservation.