Georgia, the Cherokee, and the Execution of Corn Tassel

The United States has never been particularly comfortable with the idea of Indian nations and Indian people within its territorial boundaries. Like the British before them, the United States viewed Indians as impediments to “progress” who needed to be removed to make way for non-Indian economic development. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, President Thomas Jefferson recommended that all Indians be removed from the United States and given reservations west of the Mississippi River. In 1830, this recommendation was translated into reality with the passage of the Indian Removal Act. In Georgia, the greed for Cherokee land, coupled with racism, resulted in the execution of Corn Tassel, a Cherokee man.

What Came Before:

In 1827, the state of Georgia passed a series of resolutions to take control of Indian lands within the state. The resolutions insisted that the Cherokee had no legitimate claims to land within the state and declared that Georgia law was to apply to the Cherokee. Theda Perdue and Michael Green, in their book The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southeast, report:

“Denouncing the Cherokee constitution as outrageous and claiming that the establishment of a sovereign Cherokee republic was unconstitutional, the legislature announced that Georgia had sovereignty over all the lands within its boundaries and asserted that it could take possession of the country occupied by Indians whenever and by whatever means it pleased.”

Georgia denied the validity of treaties with the United States that recognized tribal sovereignty and land rights. Georgia also demanded that the federal government honor the Compact of 1802 and remove the Cherokee from Georgia.

President Adams warned Georgia that these actions violated the treaties between the United States and the Indians. Furthermore, the United States, according to the President, would use military force to uphold these treaties. In response, Georgia called up its militia and occupied some Creek towns. The federal government backed down from any confrontation.

In 1828, the Georgia House of Representatives passed a resolution requesting the governor to ask the president of the United States to remove all Indians from the state.

In 1828, the state of Georgia also adopted legislation which extended state control over all Cherokee lands within the state. The new legislation declared all Cherokee laws to be null and void and prohibited Indians from testifying against non-Indians. As a result, groups of non-Indians invaded Cherokee country, taking Cherokee cattle and horses, assaulting those who resisted, and taking possession of Cherokee homes. According to the law, all Cherokee were to leave the state by 1830 unless they were given permission to stay by the Georgia legislature.

The following year, the state of Georgia enacted legislation which declared

“that no Indian or descendant of an Indian residing within the Creek or Cherokee nations of Indians, shall be deemed a competent witness in any court of this state to which a white person may be a party.”

Anthropologist Charles Hudson, in his book The Southeastern Indians, describes the result:

“In effect, this gave the whites – any white – a license to steal and do mayhem.”

In preparation for removal, President Andrew Jackson in 1830 ordered federal troops to be withdrawn from Cherokee lands in Georgia, leaving the Cherokee at the mercy of state residents at the time when Georgia was surveying the lands to open them for non-Indian settlement. At this same time, the Georgia Guard was created. Walter Echo-Hawk, in his book In the Courts of the Conqueror: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided, reports:

“To enforce Georgia’s growing body of anti-Cherokee laws, a special paramilitary force was created—the infamous Georgia Guard. Its mission was to enforce state law within the Cherokee Nation, arrest violators, ‘protect’ Cherokee gold mines, and otherwise harass and intimidate the Indians.”

In a report for the Niles Weekly Register, Colonel Gold (whose daughter was married to Elias Boudinot, the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix) reported that the Cherokee afford

“strong evidence that the wandering Indian has been converted into the industrious husbandman; and the tomahawk and rifle are exchanging for the plough, the hoe, the wheel, and the loom, and that they are rapidly acquiring domestic habits, and attaining a degree of civilization that was entirely unexpected, from the natural disposition of these children of the forest.”

The Cherokee National Council met in New Echota even though state law forbade it. The council unanimously adopted resolutions protesting removal.

The Cherokee sent a delegation to Washington, D.C. to present their grievances against the state of Georgia. The delegation included Richard Taylor, John Ridge, and William Shorey Coodey. In Washington, however, the Secretary of War refused to recognize them as a legally constituted delegation as they had not come with authority to discuss a removal treaty.

In Washington, D.C. President Andrew Jackson delivered a special message to the Senate. In his book Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes, Grant Foreman reports:

“He frankly announced himself as the champion of Georgia in her controversy with the Indians and as frankly disclaimed any intention to enforce the treaties made by the government with these Indians for their protection, wherein they conflicted with the pretensions of Georgia.”

In 1830, the Georgia state governor issued a proclamation prohibiting Indians from taking any more gold from their lands. According to the proclamation, the state had the right to all gold and silver found on Indian lands.

Corn Tassel:

To deal with the state of Georgia, Cherokee chief John Ross hired the Georgia law firm of Underwood and Harris and the Baltimore law firm of William Wirt. Wirt was a former attorney general and was described as “the country’s greatest expert in Indian law.” Wirt urged the Cherokee to file a case which would test their rights in the Supreme Court.

The test case involved Corn Tassel (Corn Tassels) who killed another Indian on Cherokee land. In spite of Cherokee jurisdiction, Corn Tassel was tried in a County Superior Court, found guilty, and sentenced to hang. Attorney Walter Echo-Hawk reports:

“He was prosecuted under a set of state laws enacted to harass, intimidate, and drive the Cherokee Nation out of Georgia. The Georgians wanted Cherokee land. And they wanted the Cherokee to leave.”

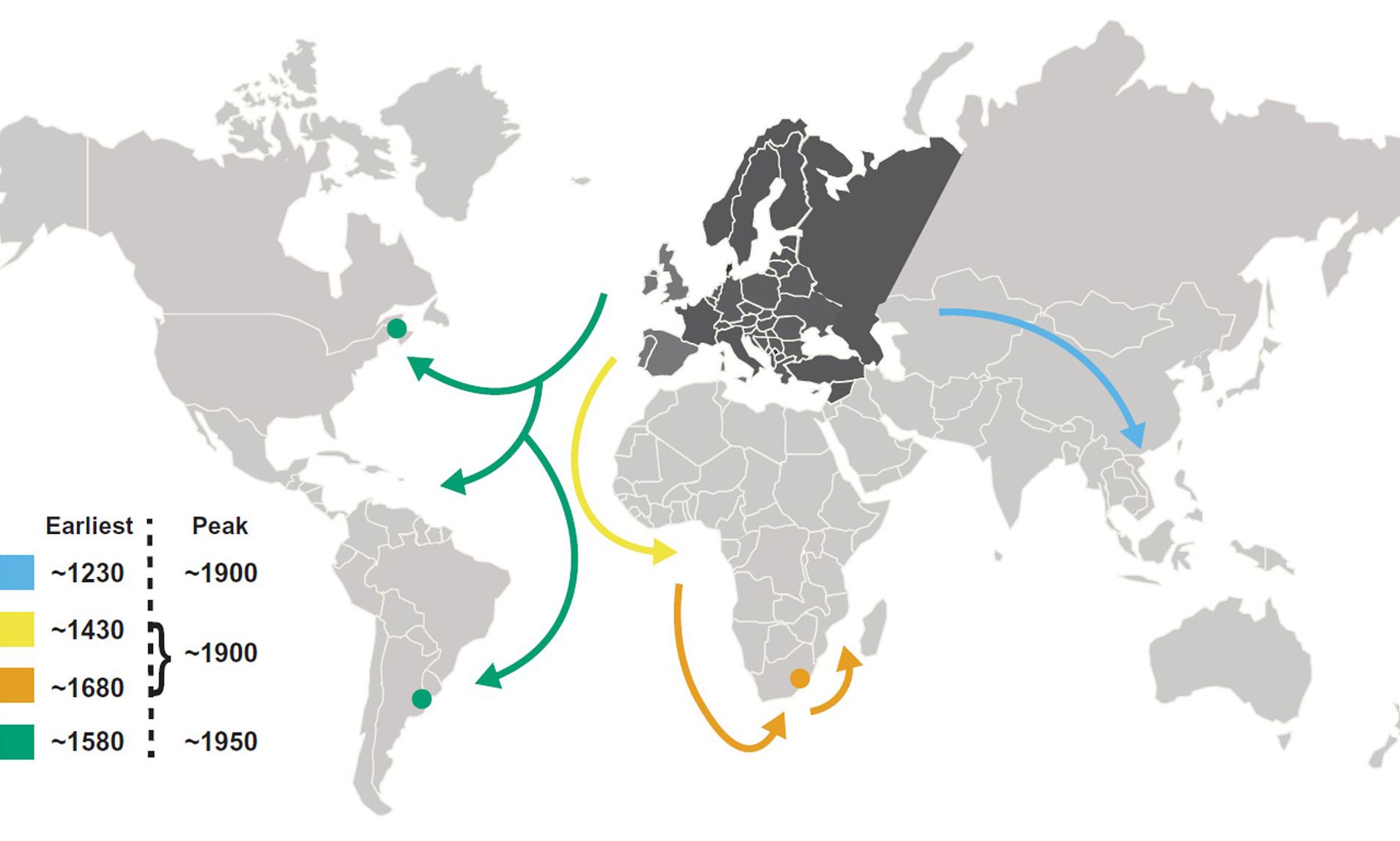

The case was appealed and a panel of state judges found that the state had full criminal and civil jurisdiction over the Indian tribes within their boundaries. Furthermore, the panel found that the British prior to the American Revolution had held title to the land by right of discovery. In the appeal, the Cherokee argued that the extension of Georgia laws over the Cherokee was unconstitutional as this violated the Treaty of Hopewell which was the supreme law of the land. The state, on the other hand, asserted that the treaty was void because the federal government had no right to treat with Indians within the limits of the state. According to the state, the Cherokee held no political or property rights and that Indian tribes were inferior. Walter Echo-Hawk reports:

“Their Tassels opinion espoused a dark southern view of Indian rights—an amoral world where aboriginal affairs are governed exclusively by the states without federal interference, in which Indians are an underclass; a place where treaties are void and tribes hold no political, property, or human rights.”

Wirt appealed to Chief Justice John Marshall who granted a writ of error and ordered the state to appear before the Supreme Court in Washington. Instead of complying, The Georgia legislature was called into special session and voted to defy the writ and to hang Corn Tassel. Governor Gilmor told the legislature that the Supreme Court had no jurisdiction to intrude on Georgia and he promised to disregard orders from the Court. Walter Echo-Hawk reports:

“Since Corn Tassels’s appeal to the United States Supreme Court had been granted, his execution should have been stayed. However, defiant and fearful Georgia could never allow the high court to review the state’s spurious race laws.”

Two days later Corn Tassel was hung. Walter Echo-Hawk reports:

“Corn Tassels had to die posthaste so Georgia could safely evade federal judicial review and continue its repugnant policies without outside interference from Washington do-gooders.”