Apache Warfare

While many non-Apache scholars and popular writers have labeled all the Apache as a fierce, war-like people, in actuality warfare was not glorified as it was in some other culture areas, such as the Great Plains. Warfare, in the form of raiding, was often an economic activity. Anthropologist Keith Basso, in his book The Cibecue Apache, notes:

“In pre-reservation days a significant portion of the Western Apaches’ meat supply consisted of stolen livestock.”

The Western Apache regularly raided the Pima and the Papago, as well as Mexican farmers in Arizona, Sonora, and Chihuahua. Relations with the Navajo were sometimes friendly and sometimes hostile. The goal of raiding was to acquire sheep, goats, horses (used for transportation as well as food), burros, mules, oxen, and cattle.

In addition to livestock, Apache raiders often captured women and children. According to Basso:

“Women prisoners were expected to work hard, and those women who did so ungrudgingly were considered a definite asset. Similar demands were made on child captives, and so long as they did not attempt to escape they were accorded many of the same privileges as Apaches their own age.”

In addition to waging war for economic reasons, the Apaches would also go on raids for vengeance and for personal aggrandizement.

Anthropologist Colin Taylor, in his book Native American Hunting and Fighting Skills, reports about the Apache:

“Members of war expeditions customarily traveled on foot, trusting to their well developed muscle and lung power to advance upon, or escape from, the enemy.”

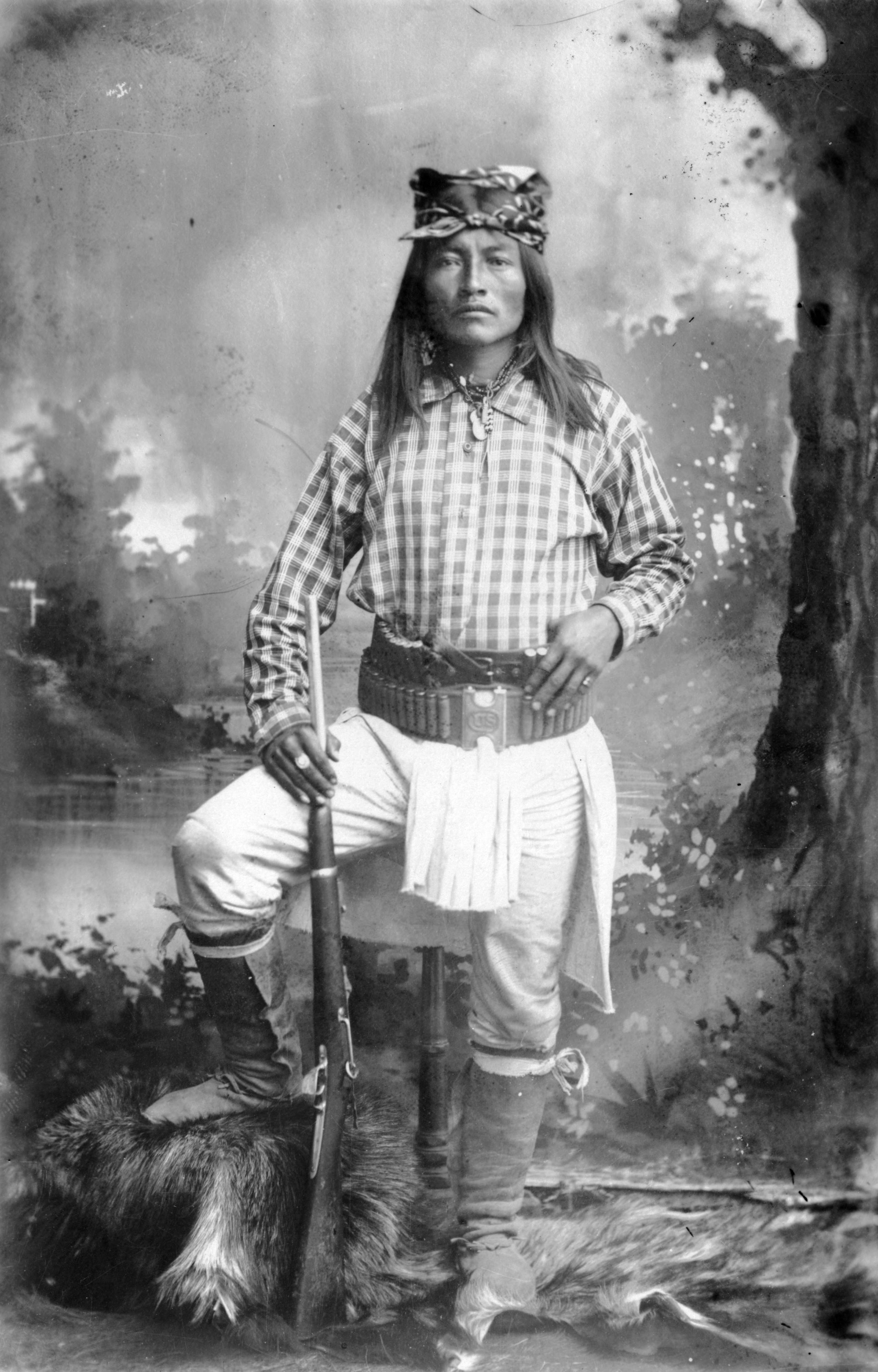

Apache warriors would carry with them only their weapons (bow and arrows, and later, a rifle), some dried food, and a canteen.

Ethnohistorian Robert Jackson, in his book Indian Population Decline: The Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1687-1840, reports:

“The Apaches generally lived and waged war in small bands and they had no large-scale political organization, which would have allowed for a more sustained form of warfare.”

Occasionally the bands would cooperate for a short period of time.

In his book A Clash of Cultures: Fort Bowie and the Chiricahua Apaches, historian Robert Utley writes of the Chiricahua Apache:

“Although traveling in small groups, usually on foot, they could swiftly unite in larger gatherings for ceremonies or war.”

Historian Robert Utley describes the Apache warrior:

“Prepared from infancy, the warrior was a master of stealth, cunning, alertness, and fighting skills. He was a superb specimen of physical strength and endurance, running miles without tiring and foregoing food and water for long periods of time.”

One of the favored war strategies of the Apache was the ambush. In one instance, an Apache war party neared a Mexican town and four of the warriors approached the town. They were seen by the Mexicans who then sent an army after them. The four warriors led the Mexican army into an ambush where the rest of the Apache warriors were easily victorious.

Bernice Johnston, in her book Speaking of Indians With An Accent on the Southwest, writes:

“An Apache warrior never fought unless he had the advantage.”

She goes on to say:

“To him, bravely standing ground against overwhelming odds was pretty silly thinking. He simply faded away and returned when he had a better chance.”

The Jicarilla Apache, unlike their Plains Indian neighbors, preferred to kill their enemies rather than simply counting coup. According to historian Veronica Tillar, in her book The Jicarilla Apache Tribe: A History:

“Individual Jicarilla warriors did not take scalps, but deferred this privilege to the party leader who had made arrangements before the sojourn with the right medicine man.”