Desecrating Indian Graves

( – promoted by navajo)

When the Pilgrims arrived in North America in 1620 they found a land which had already been depopulated by European diseases and which contained many fresh graves. One of their first acts upon landing was to rob an Indian grave. In this act they were following the grave robbing traditions of the Spanish who had arrived in North America before them and they were setting the stage for the Americans who would follow them.

In one instance the Pilgrims came upon the fresh grave of the mother of Massachusett leader Chickataubut. They opened the grave and stole from it two bearskins which had been interred with the corpse. This did not engender friendly relations with the Massachusett who viewed their actions as a form of sacrilege.

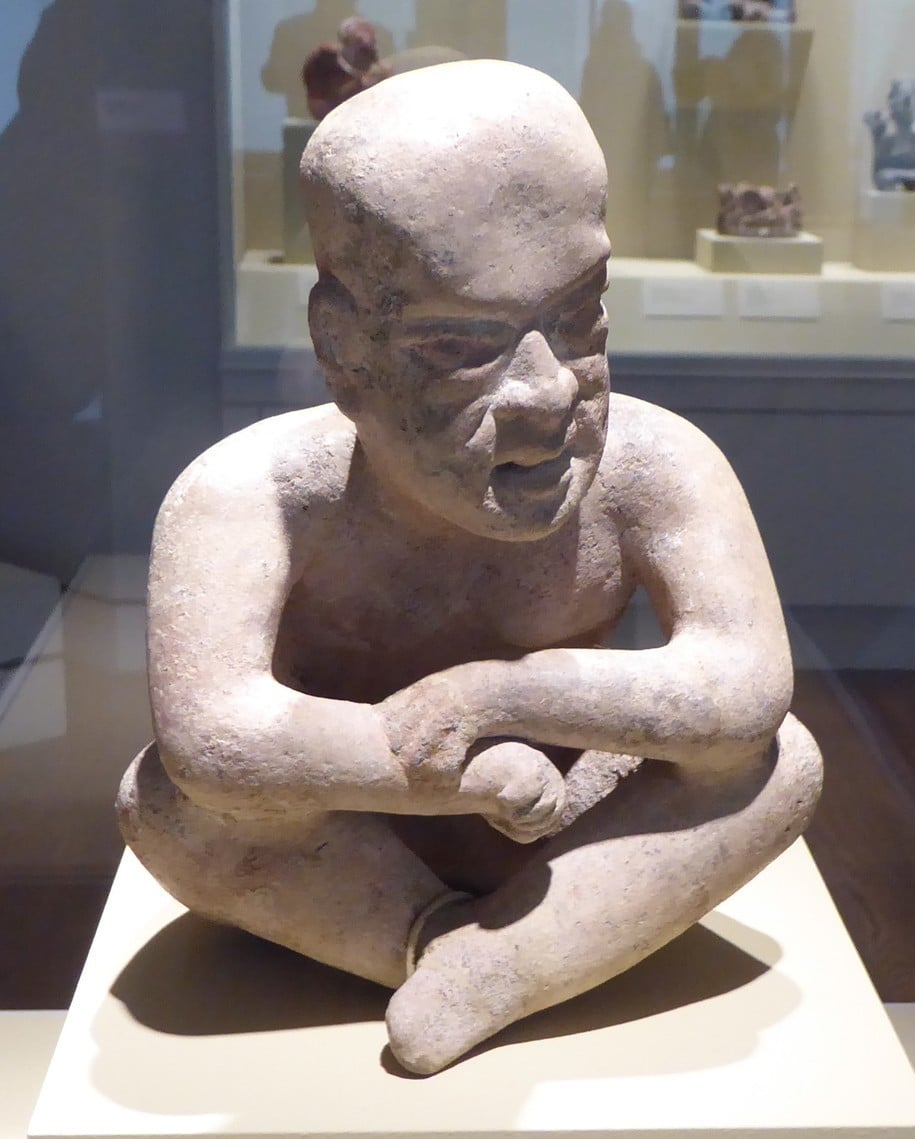

In another instance, the Pilgrims found a place that looked like a grave which was covered with wooden boards. The Pilgrims dug down into the grave and found several layers of household goods and personal possessions. They also found two bundles. In the smaller bundle they found the bones of a young child wrapped in beads and accompanied by a small bow. In the larger bundle they found the bones of a man. The man’s skull still had fine yellow hair and with the bones were a knife, a needle, and some metal items. The grave appeared to be that of a blond European sailor, shipwrecked or abandoned on the Massachusetts coast who had then lived as an Indian. He had perhaps fathered an Indian child, and had been buried in an Indian grave.

The Pilgrims also stumbled into a Nauset graveyard where they found baskets of corn which had been left as gifts for the deceased. As the hungry Pilgrims were gathering this bounty for themselves, they were interrupted by a group of angry Nauset warriors. The Pilgrims retreated back to the Mayflower empty-handed.

Indians were often offended by the grave robbing of the English colonists. While Europeans viewed grave robbing, or least grave robbing that involved European dead, as offensive, they seemed to have little concern regarding the robbing of Indian graves. In 1654, three English colonists robbed the grave of the sister of Narragansett sachem (chief) Pessicus. The Narragansett sachem, along with 80 warriors, tracked the robbers to Warwick where they met with Roger Williams. Williams convinced them to bring charges against the leader of the robbers in an English or Dutch court. However, the case was eventually dismissed when the Narragensett failed to show up in court. The Narragensett did not understand the workings of the European court system and their need to appear.

Like the English, the Americans did not feel that it should be a crime to rob an Indian grave. When nine Americans opened and robbed the grave of the daughter of Narragensett sachem Ninigret in 1859, three Narragensett men brought suit against them. A large number of grave goods were taken from the grave and distributed among Harvard’s Peabody Museum, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and private collectors. Even as these men were being arraigned and questioned, other graves at Indian Burial Hill were being opened and looted. While written accounts indicated that the men were acquitted, the judicial records show that the charges were never prosecuted.

The United States government actively promoted and encouraged the robbing of Indian graves. In 1865, the U.S. Surgeon General issued orders to all military medical officers to collect specimens for the Army Medical Museum. The assistant surgeon general explained the reason for collecting skulls: “The chief purpose in forming this collection is to aid the progress of anthropological science by obtaining measurements of a large number of skulls of aboriginal races of North America.” In response, army officers were soon systematically robbing graves on Indian reservations so that the bones, or at least the skulls, could be shipped to the newly founded Army Medical Museum. One medical officer reported: “I secured the head in the night of the day he was buried.”

Another order to obtain Indian skulls for the Army Medical Museum was issued by the Army Surgeon General in 1868. Under this order, over 4,000 Indian heads were taken from corpses at battle grounds, prisoner of war camps, hospitals, and Indian graves. Any grave goods found with the skulls were donated to the Smithsonian Institution.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many private collectors sought to obtain the skulls of famous Indian chiefs. In 1886, the grave of Nez Perce Chief Joseph (the elder, the father of Chief Joseph who was involved in the 1877 Nez Perce War) was opened and his skull was taken. The skull was later exhibited in a dentist’s office in Baker, Oregon.

The grave robbers also sought the goods which were buried with the Indian dead. In 1903, the grave of Columbia chief Moses was robbed by non-Indians who took his gold watch, his medal from Washington, D.C., and his beadwork. As the grave robbers fled from the grave, they dropped his pipe. Some boys later found it, smoked it, and became ill.

In 1911, Americans were systematically looting Palouse graves in Washington state for curios which they then sold in Eastern markets. Chief Big Sunday led a delegation to Walla Walla where they appealed to a judge to stop the vandalism. The judge ruled against the chief and the grave robbing continued. For many Americans, Indian graves were simply one more resource, like gold and timber, which should be made available for them to harvest.

In 1918, members of the Skull and Bones Society of Yale University robbed the grave of Apache leader Geronimo. His skull and femur have been incorporated into their rituals ever since this time. In 2009, the descendents of Apache leader Geronimo filed suit against Yale University asking for the return of Geronimo’s remains. The suit was filed on the 100th anniversary of Geronimo’s death by his great-great grandson Harlyn Geronimo. As of this writing, the case has not been heard.

In many communities and families in the U.S., the looting of Indian graves has been, and continues to be, an honored avocation and profession. Indian artifacts are often seen as a type of natural resource. The looters often see nothing wrong with scattering Indian bones as they dig through the graves so that they can get artifacts for personal display or to sell to other collectors. Laws regarding Indian graves often apply only to those graves located on federal lands. As late as 1987, a Kentucky landowner was paid $10,000 for the right to loot 650 Indian graves located on the property.

The United States took action in 1906 to stop some of the grave robbing: the Antiquities Act made it a criminal offense to appropriate, excavate, injure, or destroy historic or prehistoric ruins or objects of antiquity located on federal lands. The Act was crafted with no input from American Indians. While the actions of grave robbers have been illegal for more than a century, the courts and law enforcement agencies often fail to see any harm in their actions. Actions brought against grave robbers have often been dismissed by the courts, and the few that have been convicted have been given light sentences. One analysis of the convictions under the 1979 Archaeological Resources Protection Act shows that most people convicted of looting Indian graves are given probation, and, when sentenced to prison, the sentence is usually less than one year.

In New Mexico in 1992, an Anglo charged under the Archaeological Resources and Protection Act pled guilty to looting Navajo graves. He was given four years probation and a $5,000 fine. During his career as a grave robber, the man admitted to uncovering many graves and throwing the skeletons to the winds while searching for ancient artifacts to sell to “art” collectors.

In Utah in 1997, a judge reduced the sentence of a man convicted of plundering an Anasazi burial ground and leaving an infant’s bones strewn about the site. The sentence, given to a man described as a “third generation pothunter”, was originally considered the most severe sentence ever given a pothunter. The judge reduced the sentence from 78 months to 63 months by disallowing the use of the “vulnerable victim” sentencing provision. Originally, the disinterred bones of the infant had been considered a “vulnerable victim.”

The looting of graves, however, continues. In 1999, 80% of the graves in a traditional Snoqualmie burial ground in Washington were looted by professional grave robbers using a backhoe. In 2001, the water levels of the Missouri River fell and exposed many Indian burials. With the low water, the number of people looting the graves for Indian artifacts increased dramatically. Many of the exposed graves were supposed to have been removed by the Army Corps of Engineers prior to the damming of the river. Indian people have often complained about the lax attitude of the Corps regarding Indian graves.

As a result of a federal undercover investigation in 2009, 26 people were arrested in Utah for the theft of American Indian antiquities. The U.S. Attorney for Utah, Brett Tolman said:

“The public needs to understand that looting artifacts, many considered sacred by Native Americans, from public and tribal lands is simply not going to be tolerated. It is clear that there is a continued need for education on the serious nature of these crimes.”

Under the law, the defendants could face up to 10 years in prison. The judge, however, ignored sentencing guidelines, and simply gave the first two defendants probation. This sends a message that this is not considered a serious crime.