Kill the Indian, save the man

( – promoted by navajo)

This was official U.S. government policy towards the education of Indian Children for decades.

A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.

Capt. Richard H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans

In one sense I agree with Pratt’s sentiments. But only in the belief that education is critical for all peoples. But an education that destroyed cultures, families, self-worth and identity is what Pratt proposed, what Congress agreed with and what is a large part of the problems found in the native community up to this day.

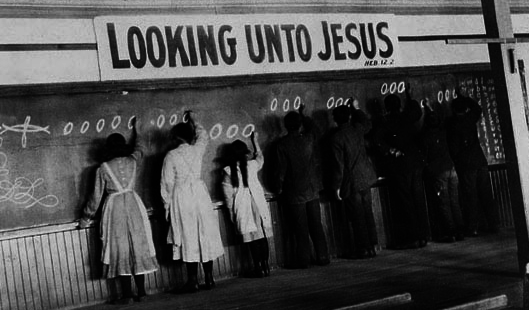

The first schools weren’t so bad in that they were on the Reservations where the kids could live at home and be with their families. However, these schools soon gave way to Indian Boarding schools. These boarding schools were set up with the express purpose of separating Indian children from their families, the communities and their traditional beliefs, their whole world in fact. The government believed the only way to make the Indian what they thought he should be was in fact to kill the Indian in him. Unfortunately, all the really succeeded in doing is destroying the man (or woman) in many cases.

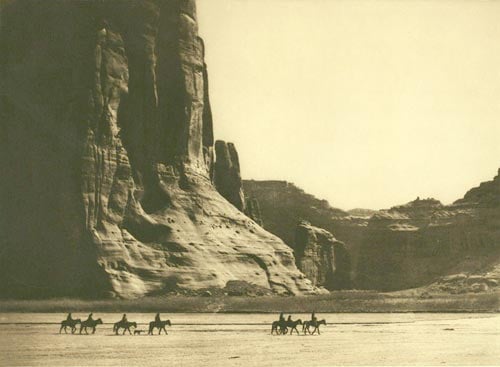

Most of the Indian parents had no problem with schooling for their children. They fought for it, even knowing that their kids would be taught in English and would to an extent begin to adopt White ways. Being forced onto lands which could not support the traditional ways of life, these parents knew that it was impossible to live in all the traditional ways and that the only way out of the extreme poverty forced upon was through education. But they were also determined that their children would hold onto their traditions, beliefs and culture while learning to function in the “white” world.

The government vehemently disagreed with this. Their belief was that only way to take care of the Indian “problem” was to take generations of Indian children, remove them from their families and all they had ever known and loved and in this way destroy their culture. For the many Native families whose kids were forced to attend boarding schools all the government really accomplished in many cases was to destroy Indian communities and families. I do not the exact number of Indian children who attended boarding schools. I can tell you that in the 1930’s there were approximately 300,000 Native Americans in the U.S. Of these about 100,000 had attended boarding schools for some period of time.

The boarding schools were definitely not the type that white people sent their kids to get the best education possible. The Indian boarding schools were often run like the Russian gulag camps set up for political dissidents with a bit of education thrown in. Only in the case of Indians, it was children who were being raised by “cultural dissidents” who were sent to be reeducated. And the farther from home they could sent the better. In many cases the children would not see their families for years. And some never saw their families again. The conditions in the boarding schools were deplorable more often than not. The nutrition was inadequate, they were often filthy and there was next to no healthcare. Disease was rampant, and children with TB and other contagious diseases often not only lacked medical care, they were in many cases left to live in the same dormitories and attend classes with the kids who would then be exposed to these diseases. When parents tried to prevent their children from being sent away, food rations were cut, arrests made and the children were literally kidnapped and sent away. Once at boarding schools, many children tried to run away. Punishment for them was harsh, from beatings to starvation and isolation. In one case at Wrangell Institute boarding school which my father attended, a girl who had runaway was caught and forced to stand tied up in a hallway for hours. When she grew tired and leaned or tried to sit she was beaten with a stick. When she fell, she was beaten until she managed to get up again.

Many children died at these boarding schools, and the extent of these deaths is just now being investigated. For example:

During the first decades of the federal government’s Indian boarding schools, stories of morbidity and mortality among students were prevalent. Don’t Know How, a Lakota father, shared an all-too-common experience. Anticipating the return of his daughter from Hampton (Virginia) Institute, Don’t Know How constructed a new house, purchased a store, and adopted to the extent he could the trappings of white America. His daughter, meanwhile, returned from Hampton suffering from consumption. Within days she succumbed to the scourge of Indian Country: tuberculosis. Soon thereafter, Don’t Know How’s other daughter departed for Hampton, where in a few years she followed her sister “to the little cemetery on the hill.” In Hampton’s first ten years of educating American Indian students, one of every eleven students died (31 of 304) at school and one of every five died as did Don’t Know How’s daughters soon after returning home.

http://muse.jhu.edu/…

“A more complete history of the abuses endured by Native American children exists in the accounts of survivors of Canadian “residential schools.” Canada imported the U.S. boarding school model in the 1880s and maintained it well into the 1970s-four decades after the United States ended its stated policy of forced enrollment. Abuses in Canadian schools are much better documented because survivors of Canadian schools are more numerous, younger, and generally more willing to talk about their experiences.

A 2001 report by the Truth Commission into Genocide in Canada documents the responsibility of the Roman Catholic Church, the United Church of Canada, the Anglican Church of Canada, and the federal government in the deaths of more than 50,000 Native children in the Canadian residential school system.

The report says church officials killed children by beating, poisoning, electric shock, starvation, prolonged exposure to sub-zero cold while naked, and medical experimentation, including the removal of organs and radiation exposure.”Recent invesitigations of U.S. boarding schools have reported the following:

Both BIA and church schools ran on bare-bones budgets, and large numbers of students died from starvation and disease because of inadequate food and medical care. School officials routinely forced children to do arduous work to raise money for staff salaries and “leased out” students during the summers to farm or work as domestics for white families. In addition to bringing in income, the hard labor prepared children to take their place in white society-the only one open to them-on the bottom rung of the socioeconomic ladder…

Native scholars describe the destruction of their culture as a “soul wound,” from which Native Americans have not healed. Embedded deep within that wound is a pattern of sexual and physical abuse that began in the early years of the boarding school system. Joseph Gone describes a history of “unmonitored and unchecked physical and sexual aggression perpetrated by school officials against a vulnerable and institutionalized population.” Gone is one of many scholars contributing research to the Boarding School Healing Project.

Rampant sexual abuse at reservation schools continued until the end of the 1980s, in part because of pre-1990 loopholes in state and federal law mandating the reporting of allegations of child sexual abuse. In 1987 the FBI found evidence that John Boone, a teacher at the BIA-run Hopi day school in Arizona, had sexually abused as many as 142 boys from 1979 until his arrest in 1987. The principal failed to investigate a single abuse allegation. Boone, one of several BIA schoolteachers caught molesting children on reservations in the late 1980s, was convicted of child abuse, and he received a life sentence. Acting BIA chief William Ragsdale admitted that the agency had not been sufficiently responsive to allegations of sexual abuse, and he apologized to the Hopi tribe and others whose children BIA employees had abused.

The effects of the widespread sexual abuse in the schools continue to ricochet through Native communities today. “We know that experiences of such violence are clearly correlated with posttraumatic reactions including social and psychological disruptions and breakdowns,” says Gone.The abuse has dealt repeated blows to the traditional social structure of Indian communities….. Today, sexual abuse and violence have reached epidemic proportions in Native communities, along with alcoholism and suicide. By the end of the 1990s, the sexual assault rate among Native Americans was three-and-a-half times higher than for any other ethnic group in the U.S., according to the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics. Alcoholism in Native communities is currently six times higher than the national average. Researchers are just beginning to establish quantitative links between these epidemic rates and the legacy of boarding schools.

http://www.amnestyus…

In my family’s case, my dad was sent to a boarding school about 800 miles from home. This was in the early 1930’s and that was an incredible distance to cover in those years.

His sister was sent from Alaska to a boarding school in Kansas. My grandmother was not able to stop this. It was only when her husband (who was white) returned after several years in Sweden that he was able to get the kids back. In my mother’s case, she and her brothers and sisters were lucky because a church had started a local school for Indian kids in the town of Saxman which they were able to attend.

As I said they were among the lucky ones. The kids and parents who were separated throughout their school years were harmed in two ways people don’t always consider. First, children learn to parent by being parented. When they do not have role models to parent, they literally do not know how. So when they have kids, they are often lost as to how to raise them.

In interviews with some of the individuals who had ateended boarding school, comments like this were heard”

We heard from several respondents that their time away at boarding school, even when a good experience, contributed to their lack of parenting skills. One respondent said the following:

Although we had some chances to do things, but we did miss out a lot that we could’ve learned from our parents. And then one thing that I often talk to my friends about is the fact that we missed out on being raised by our parents, being taught by our parents. And we missed out in having the opportunity to observe our parents raise kids our age. Because we were kids, we were 12 years old, 11, 12, 13 year old kids being away. The guidance, we missed out the guidance that we could have received from them… So when I see parents not doing anything with their children,

not talking to their children, not disciplining their children, parents that are my age, I think about that. Because when I look at the parents, I see they’ve gone to St. Mary’s or Bethel or Edgecumbe or Chemawa, Oregon, Chilocco, Oklahoma, all those boarding schools that were popular at that time, they’re the parents that went.The phenomenon of children being removed from their homes affected not only the students, but their home villages as well. One respondent described the phenomenon of a healthy village being turned upside down: When the children were taken away to boarding school the parents turned to

alcohol for solace. Three other interviewees, from two additional communities, shared similar tales about the adults from their villages becoming alcoholics after the children were sent away.http://www.iser.uaa….

When the kids were taken from their parents, many times the parents just gave up. I’m sure most of us realize that when we have kids, we (hopefully) realize we have to grow up, become responsible, and work for our kids future. However, when kids on the reservation were taken away, that incentive was lost for many parents. With their kids torn from them, leaving them depressed and despondent, without hope, it was not unusual for the parents lives to also spiral downward. It has led to cycle of despair for many families on many reservations. Fortunately, many The thing people should be surprised about concerning the level of abuse and neglect on, (and often times off) reservations is that it is not worse than it is.

The work of women like Georgia Littleshield is what is going to turn this type of thing around. I thank all of you who support her.