The Removal of the Ponca Indians

( – promoted by navajo)

In 1877 the United States government informed the Ponca that they were going to be removed from their traditional homelands in Nebraska and reassigned to a reservation in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The Ponca, a nation which had been at peace with the United States and was considered friendly, were to be moved from their reservation on the Nebraska-Dakota border to Oklahoma because their reservation had been given to their traditional enemies, the Sioux, in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

The Ponca first heard about their proposed removal a year earlier. At this time, the chiefs called a great council to discuss the matter. Speaking to the representatives from the American government who attended the council, Standing Bear said:

“This land is ours, we have never sold it. We have our houses and our homes here. Our fathers and some of our children are buried here. Here we wish to live and die.”

The representatives from the American government simply told the Ponca that Indian Territory was a better country.

In 1877, the Ponca were informed of their impending relocation during a Christian church service. During the service, the Indian agent addressed the Ponca and painted a glowing picture of their new lands in Oklahoma. Standing Bear responded to the announcement by pointing out to the agent that they had never sold their land nor had they ever asked to go to Indian Territory. He also reminded the agent that the Ponca had kept their treaty with the United States and that they had harmed no one.

Standing Bear, White Eagle, Standing Buffalo, Big Elk, Little Picker, Sitting Bear, Little Chief, Smoke Maker, Lone Chief, and White Swan were then taken to Oklahoma to see their new lands. For the journey south, the government purchased “civilized clothing” (primarily shirts and vests) for the chiefs. Once in Oklahoma, the Ponca chiefs found that the land did not suit them. They felt that this was not a land where corn and potatoes would easily grow. The land did not compare favorably with their lush green homeland in Nebraska. At this point, the Ponca chiefs realized that once again the Indian agent had lied to them.

The Ponca leaders informed the government that the heat, humidity, and poor soil conditions did not suit them. The Indian agent told them that they were to select land in Indian Territory or starve. The government then refused to take them back north. The chiefs were stunned to find that they were going to be stranded in a strange land because they disagreed with the government. They had visions of dying here without ever seeing their families again.

They had only $8 between them and only the clothes on their backs, They had almost no understanding of English. In spite of this, the chiefs made the 500 mile walk back to Nebraska where the Indian agent had them arrested.

The Ponca chiefs met with Omaha chief Iron Eyes (Joseph La Flesche) and his daughter Bright Eyes wrote out a statement from the chiefs which tells of their ordeal. She then wrote a telegram to the President.

In response to their complaints, an inspector from the Indian Office and the Indian agent called for a council with the Ponca. Before the inspector could address the council, Standing Bear came to his feet. Pulling his red council blanket around his shoulders, he asked why the Indian Affairs men had come to the Ponca reservation when they had not been invited. He concluded by telling the Indian Office men to leave at once.

Standing Bear and his brother Big Snake were then arrested, placed in chains, and jailed for resisting the removal order. The other Ponca chiefs, however, defiantly told the Americans that they would not be removed. The Indian Office inspector simply informed the council that they could move of their own volition or the Americans would use force against them.

At sunrise, army troops-four detachments of cavalry and one of infantry-surrounded the Ponca village. The troops dragged men, women, and children from their cabins. There was no discussion, no negotiation, and no toleration of resistance. The Ponca left behind their homes, their farms, and their farm equipment.

The Ponca were marched south under escort. They were deluged with rain and two Ponca children soon died from exposure. The army showed them no mercy, forcing the wet, cold people to travel along mud-clogged byways and across swollen rivers. When a tornado struck the camp, destroying tents, damaging wagons, and injuring several people, the army simply ordered the march to continue with no delay, except for burying the dead.

It took the Ponca 50 days to reach their destination. They were informed that they were now prisoners and they would be punished if they attempted to leave the reservation. The Ponca disliked their new home, and the chiefs petitioned the authorities in Washington to return to their ancestral lands.

Nearly one-fourth of the Ponca died during their first year in Indian Territory.

A delegation traveled to Washington, D.C. where four Ponca chiefs met President Rutherford Hayes. Each of the chiefs expressed dissatisfaction with their land in Oklahoma and their desire to return to their homeland. Standing Bear reverently, respectfully told the story of how his people had been wronged. He pointed out that they were now in a bad place, and that he hoped the President would do something for them. President Hayes was astonished at the story of their forced march and told the chiefs that this is the first he has heard of it.

At a meeting in the Department of the Interior, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs informed the Ponca chiefs that there was no way that their request to be returned to the north could be honored without Congressional action. At a second meeting with President Hayes, who had now been briefed by the Department of the Interior, the President told them that the Ponca must stay in Indian Territory. He assured them that they would be treated well.

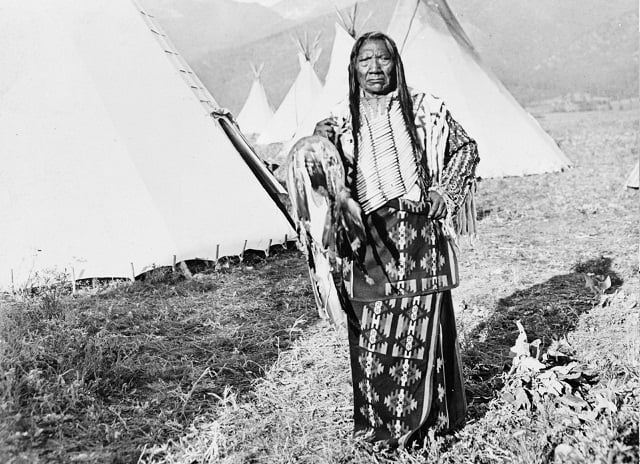

Chief Standing Bear is shown below: