WWII and American Indians: After the War

( – promoted by navajo)

World War II changed both the Indians and the reservation. Following the war, veterans returned to their reservations. In many cases they returned as warriors, victorious warriors, and unwilling to accept the secondary status assigned to them by the larger society. They faced discrimination in housing, employment, education, land rights, water rights, and voting.

In many states, it was illegal for Indians to purchase or consume alcohol. Yet many of the veterans had found that while in the military they were able to purchase and consume alcohol with no legal difficulties both on the bases and while on furlough in foreign countries. Many returned home wanting this same freedom as civilians in the United States.

Celebrations and Ceremonies:

Many of the returning veterans went through purification ceremonies. The veterans reported that these ceremonies took away the nightmares about the horrors of war.

In Illinois, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) sponsored a reception, luncheon, broadcast, and parade to honor Pima war hero Ira Hayes. The event was organized by NCAI treasurer George LaMotte (Chippewa) without the approval of the NCAI executive committee. LaMotte led a parade of 75 Indians dressed in traditional regalia in a reenactment of the flag raising at Iwo Jima. There were 60,000 people in the audience. NCAI executive board member D’Arcy McNickle (Flathead) complained that the event was unauthorized and charged that it promoted Indian stereotypes.

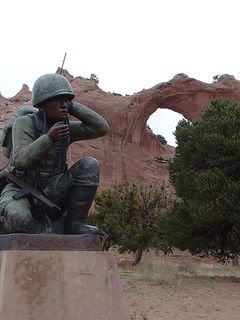

Unlike other veterans, the Navajo marines who had served as code talkers in the Pacific were told not to talk about what they had done. For these veterans there were no organized celebrations.

In Montana, tribal member The Boy opened the Gros Ventre Flat Pipe bundle to honor his vow regarding the safe return of Gros Ventre soldiers from the War. The Boy remarked:

“the rising generation of Gros Ventres would not go back to this form of worship….They are too far gone into religion of the white man.”

GI Bill:

Like other veterans, many Indians took advantage of the GI Bill to attend colleges and universities. As a result, a new generation of Indian leaders, many of whom now held degrees in law, medicine, engineering, and other fields, began to emerge. No longer were Indian nations reliant on non-Indians to provide many of the technical skills required in the twentieth century.

While the GI Bill provided many Indian veterans with an opportunity for higher education, the bill’s housing provisions could not be applied on reservations. Banks would not loan money for houses to Indians on reservations. The problem was that the Bureau of Indian Affairs would not sign a waiver to the title to the land as Indian reservations were lands which are held in trust by the federal government. There was no way to secure a loan, even under the GI Bill, without this waiver.

Voting Rights:

Indian veterans returned home with different expectations about how they were to be treated. While they had fought tyranny in Europe and in the Pacific and had been treated as equals during this fight, they returned home to find that they were still second-class citizens (and in some states, the recognition of their citizenship lacking). The Indian veterans expected to be able to vote and when states attempted to deny them that right, they took their case to the courts. Throughout the country, barriers to Indian voting began to fall.

Even though Indians had been granted citizenship in 1924 and then again in 1940, it was common for many states in the 1940s to refuse to allow Indians to register to vote.

In North Carolina, county registrars refused to register Eastern Cherokee war veterans to vote. The Cherokee appealed the decisions to the governor and attorney general, but nothing was done.

In New Mexico, the path to obtaining the right to vote was started when Miguel Trujillo, Sr. (Laguna), a teacher, attempted to register to vote and was refused by the recorder of Valencia County. Rather than just walking away and accepting non-citizenship, he filed suit to obtain his voting rights. The Court found that New Mexico had discriminated against Indians by denying them the vote, especially since they paid all state and federal taxes except for private property taxes on the reservations. The federal judge remarked:

“We all know that these New Mexico Indians have responded to the needs of the country in time of war. Why should they be deprived of their rights to vote now because they are favored by the federal government in exempting their lands from taxation.”

In Arizona, Frank Harrison and Harry Austin, both Mohave-Apache at the Fort McDowell Indian Reservation, attempted to register to vote and were not allowed to register. The Arizona Supreme Court overturned an earlier decision and agreed with the plaintiffs that their Arizona and United States constitutional rights had been violated.

The New Mexico and Arizona cases are often cited in history textbooks as the point at which American Indians finally received the right to vote. Unfortunately this was not the case and Indians had to continue that fight. American Indian veterans who had fought for American freedom in Europe and in the Pacific, now fought for American Indian freedom in the United States.