( – promoted by navajo)

Death Valley, located in California, is the hottest, driest, and lowest place in the United States. It is an area of sand dunes and wilderness. Non-Indian tourism into this desolate region actually began in 1926 and in 1933 President Herbert Hoover created the Death Valley National Monument by Presidential Executive Order. While some saw this act as the first step in transforming one of the earth’s least hospitable spots into a popular tourist destination, for the Timbisha Shoshone, the aboriginal inhabitants of the area, this action made them landless. While the Timbisha Shoshone were not forced from their traditional homeland, the control over their land (and thus over their lives) was assumed by the National Park Service. Death Valley officially became a National Park in 1994.

Death Valley, located in California, is the hottest, driest, and lowest place in the United States. It is an area of sand dunes and wilderness. Non-Indian tourism into this desolate region actually began in 1926 and in 1933 President Herbert Hoover created the Death Valley National Monument by Presidential Executive Order. While some saw this act as the first step in transforming one of the earth’s least hospitable spots into a popular tourist destination, for the Timbisha Shoshone, the aboriginal inhabitants of the area, this action made them landless. While the Timbisha Shoshone were not forced from their traditional homeland, the control over their land (and thus over their lives) was assumed by the National Park Service. Death Valley officially became a National Park in 1994.

Death Valley is called tumpisa by the Timbisha Shoshone. The name means “rock paint” and refers to the red ochre paint that can be made from a type of clay found in the valley. The name Timbisha means “Red Rock Face Paint.”

The creation of the new national monument in 1933 was the result of lobbying by the Automobile Club of Southern California. Monument planners emphasized Death Valley’s unique animal and plant life, but seemed to be unaware of the small groups of Indians living throughout the new federal park.

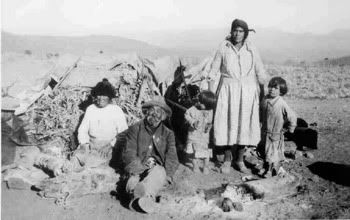

In 1936, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the National Park Service set aside 40 acres as a village site for the Timbisha Shoshone in Death Valley. The Civilian Conservation Corps built timber and adobe houses for the Timbisha. The model community was intended to provide modern homes for Indians near wage work at Furnace Creek. In addition, the community would have a trading post where the Shoshone women could market their intricate baskets and a laundry service where they could work.

For more than forty years, the Timbisha Shoshone seemed almost invisible to the National Park Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the federal government. Then, in 1978, Timbisha Shoshone leader Pauline Esteves negotiated an agreement with the Indian Health Service and the National Park Service to provide a new domestic water supply and waste disposal facilities for their village in Death Valley National Monument. The Timbisha Shoshone also purchased four trailers to augment their housing and finally receive electrical service.

In 1982, the Timbisha Shoshone obtained federal recognition from the United States government. They were one of the first tribes to obtain federal recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs federal acknowledgement process.

In 1994, the California Desert Protection Act added millions of acres to the Death Valley National Monument and made the entire area into a National Park. The act included a provision to conduct a study of the aboriginal homelands of the Timbisha Shoshone for the purpose of identifying lands which would be suitable for a reservation. The study was to be done in consultation with the tribe. Of the half a dozen tribes who had lands within a national park at this time, only the Timbisha Shoshone did not have a reservation.

Three years later, the leaders of the Timbisha Shoshone were notified by the National Park service that they would have to give up their 40 acre camp in the Death Valley National Park. While Death Valley has been a part of the Timbisha homelands for hundreds of years, the Park service had long maintained that no Indians had lived in the area.

In 1999, the National Park Service and the Timbisha Shoshone reached an agreement which gave thousands of acres to the tribe. Under the agreement, the tribe received 300 acres near the Park’s main tourist center which the tribe could use for homes, a gift shop, a medical clinic, and a motel. In addition, the tribe received 3,000 acres outside of the Park from the Bureau of Land Management.

In 2001, the Timbisha Shoshone held a celebration at their old Indian Village at Furnace Creek. Timbisha elders and the National Park Service personnel met together at a barbeque to symbolize a new era of cooperation.

Today the official website for the park says:

The Timbisha Shoshone Indians lived here for centuries before the first white man entered the valley. They hunted and followed seasonal migrations for harvesting of pinyon pine nuts and mesquite beans with their families. To them, the land provided everything they needed and many areas were, and are, considered to be sacred places.

At the present time, the Timbisha Shoshone have a village at Furnace Creek.

Leave a Reply