The Timucua

( – promoted by navajo)

photo credit: Aaron Huey |

Prior to the Spanish invasion of Florida in 1513, it is estimated that there may have been as many as 772,000 Timucua. Fifty years later, the Timucua numbered about 150,000 due to epidemic diseases brought to Florida by the Spanish and by Spanish hostilities. By 1682, there were less than 1,000 Timucua.

Timucua Culture:

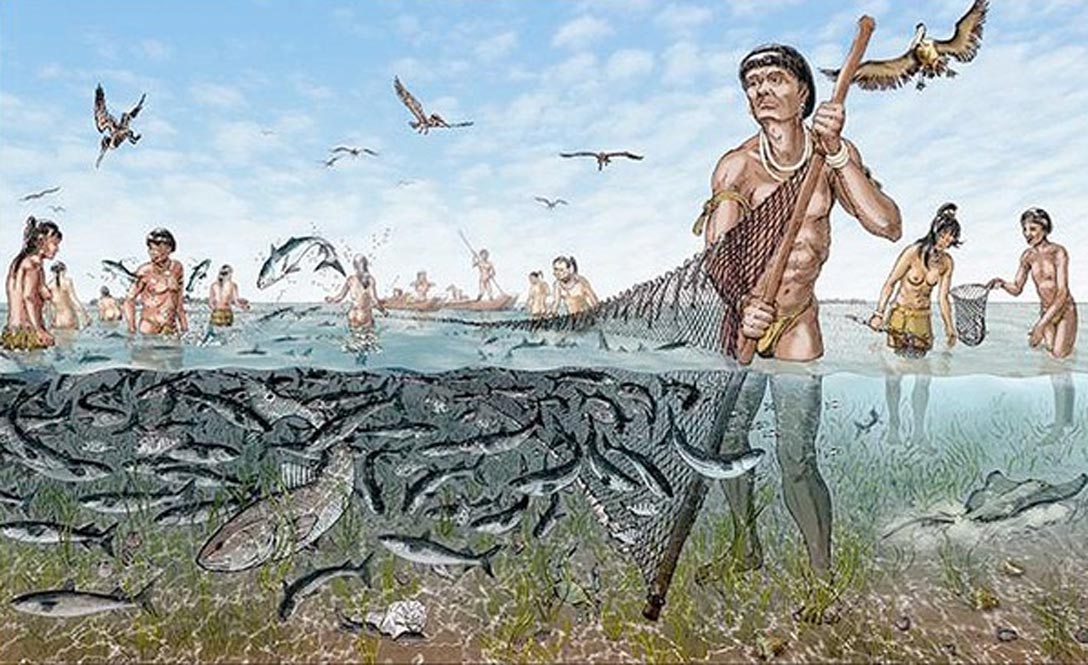

The Timucua were skilled farmers who lived in permanent villages in present-day Florida. The Timucua were a powerful centralized chiefdom with an economy based on a combination of agriculture, hunting, and fishing. At the time of initial Spanish contact (1520-1570) there were nine Timucua-speaking chiefdoms in what is now Florida: Yustega, Utina, Potano, Tocobaga, Saturiwa, Aqua Dulce, Acuera, Ocali, and Mocozo.

The early Spanish explorers described the Timucuan houses as looking somewhat like pyramids. They were built by using flexible wall posts which were anchored in the ground. Their tops were then bent together and secured. Smaller branches were then interwoven among the support posts and the structure was covered with palm thatch.

Timucua villages were generally laid out around a central plaza and ballcourt area. The villages often contained a larger communal structure and a chief’s house. Some villages contained as many as 250 houses, but many consisted of only 20-30 houses with a population of 200-300 people.

One of the features of Timucua villages was the communal warehouse. These storehouses contained foods intended to serve the entire chiefdom and were located on or near the banks of steams which could be navigated by canoes. The Timucua dried large quantities of fish, alligators, snakes, deer, and other game on wooden rakes over smoking fires. They also dried maize, beans, and squash as well as amaranth/chenopod seeds, nuts, berries, fruits, such as plums, and other foodstuffs.

The Timucua villages were organized into a series of simple chiefdoms. Each of the estimated 25-30 Timucua chiefdoms was centered on a main village whose chief (utina) received homage from two to ten other villages. Each of these other villages had its own chief (holata). Timucuan chiefs generally belonged to the White Deer clan.

Among the Timucua, the chiefs were aided in their governing by chiefly officials who were usually village elders and/or high status individuals. Village council houses were round buildings which could hold 100 people or more.

It was not uncommon for a Timucua village to have a woman chief. Some villages regularly had women chiefs. Women chiefs had the same powers as male chiefs.

Among the Timucua there were both curers (isucu) and shamans (yaba). Curers were native doctors who used various herbs, while shamans performed rituals associated with gathering food, foretelling the future, finding lost items, and many more activities.

As with other American Indian tribes, the Timucua recognized more than two genders. Some people, known as Two Spirits or berdaches, took on the cultural roles of the opposite gender. Among the Timucua, these individuals were often healers. In addition, they played an important role in funerals by carrying the dead for burial.

The Timucua and the Spanish:

The first reported contact between the Timucua and the Spanish was in 1527. Pánfilio de Narváez, with a reputation for brutality and a strong desire to find gold and wealth, invaded Florida with a force of 600. The Timucua, hearing about Spanish brutality, left their village before the Spanish arrived, hoping to encourage the Spanish to leave by offering no hospitality. The Spanish entered the empty village and reported that it included one building which could hold 300 people. However, the Spanish find a gold rattle that ignited their gold-lust. The Spanish claimed the country for Spain

The Spanish continued their march north to Tampa Bay. At one village the Franciscan priests ordered that the revered remains of the Timucua ancestors be burned. The Spanish marched northward without seeing any natives. The Timucua considered their policy of avoidance to be successful.

In 1528, some Spanish explorers were taken to a Timucua village where they found many European goods. The Timucua explained that the goods had come from a ship which had wrecked in Tampa Bay.

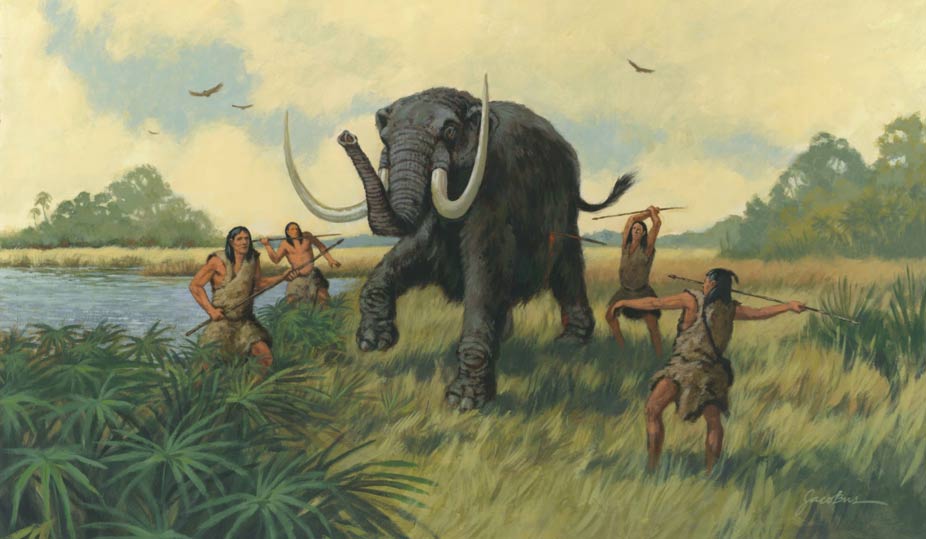

In 1539, Hernando de Soto began his exploration of the southeast. He landed in Tampa Bay, Florida with a force of 200 horsemen (with 223 horses), 400 foot soldiers, some fighting dogs, and a small herd of hogs for food. Like other Spanish explorers, the Spanish Crown gave de Soto a license to plunder. The Spanish would seize local chiefs and hold them for a ransom of bearers, women, and corn. The women were forced to serve the Spanish as sexual slaves.

The Timucua near Tampa Bay were the first to encounter de Soto. The Spanish killed many Timucuans outright, tortured others, or tracked them down to be torn asunder by wolfhounds.

While the Spanish had military superiority with their firearms, horses, and dogs of war, they found that their armor was not very effective. The Timucua warriors used their atlatls (spear throwers) to launch spears which pierced Spanish armor.

The Spanish reported that they passed by many great fields of corn, beans, squash, and other plants. In one instance they reported that the fields ran for two leagues (approximately 4-5 miles) and that they spread out for as far as the eye can see on either side of the roadway. It is estimated that the Timucua had 10,000 acres under cultivation.

The Spanish noted that the Timucua-speaking capital of the Ocali chiefdom had 600 dwellings. It is estimated that the Ocali population was about 60,000 at this time.

In 1647, the Timucua helped the Spanish to put down a revolt by the Apalachee and Chisca. The revolt was led by traditional Apalachee who burned seven churches and killed three friars. The Spanish force of 31 soldiers and 500 Timucua warriors engaged a large rebel army-perhaps 8,000 warriors-in a day-long battle. In spite of the fact that the Timucua suffered heavy losses, the rebellion was quickly put down.

In 1656, the Spanish governor heard rumors of an impending English raid against St. Augustine. He ordered the Timucua, Apalachee, and Guale to assemble 500 warriors and to march to St. Augustine to help defend it. The governor also commanded the warriors and their chiefs to carry their own supplies, including the corn and food they would need for the overland trek to and from St. Augustine and for a stay of at least one month in town. Since chiefs did not traditionally carry their own burdens, some were insulted by this request. One Timucua chief, Lúcas Menéndez, flatly refused to obey the order. In addition to having to supply their own food for at least six weeks, the Indians were not to be paid for their service to the Spanish.

In rebelling against Spanish authority, Lúcas Menéndez ordered all of the Spaniards in his province, with the exception of the Franciscan friars, to be killed. Their rebellion was not against the church as Catholicism had become the Timucuas’ own religion. Their rebellion was against the military government and its mistreatment of the chiefs and their people. The Timucua rebels initially killed seven people.

The different Timucua chiefs communicated to each other by writing letters in the Timucua language. In one instance, they intercepted a Spanish dispatch written in Spanish which they were able to read.

The Spanish response to the rebellion was to send a detachment of 60 Spanish soldiers and 200 Apalachee warriors into Timucua territory. The rebels took refuge at a fort near Santa Elena de Machava. After extended talks, the Indians in the territory surrendered. The Spanish allowed most to go free, but they arrested the leaders.

Intending to punish the rebel Timucua further, the Spanish sent out a second expedition. They captured about two dozen Indians, including several chiefs, who were then tried. Half were sentenced to death and half to hard labor in St. Augustine. Those who were sentenced to death were hung at various locations in Timucua territory as a reminder of Spanish authority.