American Indian Biography: John Rollin Ridge, Cherokee Writer

( – promoted by navajo)

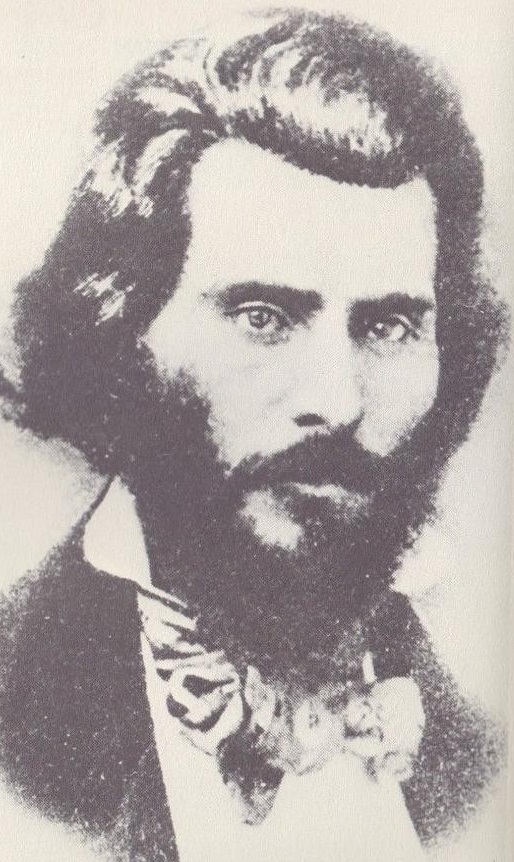

When John Rollin Ridge died in 1867 he was eulogized as one of California’s great poets and political commentator. To understand his life and what motivated him, we must start by looking at his parents: John Ridge and Sarah Bird Northrup.

In the early 1800s, the Cherokee were borrowing many European ideas. Feeling that reading and writing were important, the Cherokee invited Christian missionaries to live among them and to operate schools. The Brainard School opened in 1817 with 26 Cherokee students. Soon it was suggested that some Cherokee might enroll in the new school operated by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions at Cornwall, Connecticut. Soon a number of Cherokee students were enrolled at the school.

The curriculum at the Cornwall school included a heavy dose of religious training, working on the school’s farm (classified as “agricultural education”) and courses in geography, history, rhetoric, surveying, Latin, and natural science.

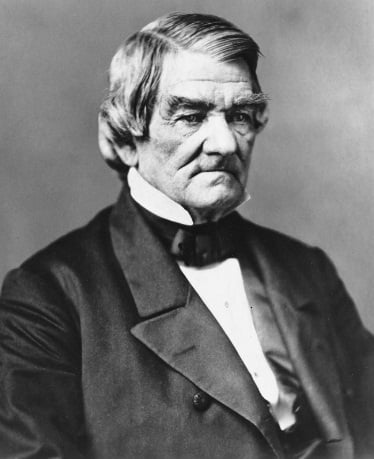

One of the Cherokee students at the school was John Ridge. However, he had problems with his hip which were aggravated by the cold winters. By 1821, his condition had worsened and so he was removed from the dormitory and placed in a private room in the Northrup home. It was there that he met and fell in love with the fourteen year-old Sarah Bird Northrup. Sarah’s family responded by sending her away to live with her grandparents. John wrote to his mother and asked for her permission for him to marry Sarah. John’s mother, insisting that he should marry a Cherokee woman, did not give her consent to the marriage.

In spite of the opposition from both families, John Ridge and Sarah Bird Northrup were finally married on January 27, 1824 in Connecticut. In order to avoid being mobbed, the couple immediately left Connecticut for Cherokee country in Georgia. The Cherokee were used to having non-Cherokee men marry Cherokee women and were dismayed to find that the Christian citizens of Cornwall, Connecticut were strongly opposed to having Cherokee men marrying non-Cherokee women.

John Rollin Ridge was born to John Ridge and Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge at Running Waters in the Cherokee Nation on March 19, 1827. John Ridge at this time was practicing law and had a half-interest it the ferry at New Echota. The family farm consisted of 419 acres and was run with the help of 18 slaves.

By 1835 the pressure from the State of Georgia and from the United States to have the Cherokee move west of the Mississippi had intensified. Census records at the time show that there was little difference between the Cherokee and non-Cherokee in terms of material culture. They lived in the same kind of homes, they raised the same crops. However, the Americans, fueled by racism and greed, wanted Cherokee land. The Cherokee at this time were divided into two factions: the Ridge party and the Ross Party. The Ridge Party led by John Ridge, Major Ridge (John’s father and John Rollin’s grandfather), and Elias Boudinot (also known as Buck Watie) saw that removal was inevitable, while the Ross Party, under the leadership of John Ross, opposed removal.

On December 29, 1835, twenty members of the Ridge Party signed an agreement with the United States in which the Cherokee would exchange their lands in the east for nearly 14 million acres of land in the west. In addition, they would receive $4.5 million and an annuity to support a school. John Ridge, Major Ridge, and Elias Boudinot were among those who signed the treaty. Upon signing, Major Ridge remarked: “I have signed my death warrant” in acknowledgement that the Cherokee nation had a law mandating death to those who sold Cherokee land.

In 1836, the Ridges and other members of the Ridge party left their traditional Cherokee homeland for Indian Territory. They settled near present-day Southwest City, Missouri and their 18 black slaves set out to clear the land and plant the crops.

The Ross Party and other Cherokee would later be forced to move to Indian Territory at bayonet point in a journey called the Trail of Tears.

In 1839, three execution squads set out to enforce Cherokee law. One of these squads forced their way into the home of John Ridge, and dragged him from his bed to the yard. While John Rollin Ridge and other members of the family watched, some of the men held John Ridge’s arms and legs while others stabbed him 29 times. They then threw him into the air and let his bleeding body crash to the ground. The execution squad then marched over his body, stamping on him as they passed. John Rollin Ridge would later write:

“My mother ran to him. He raised himself on his elbow and tried to speak, but the blood flowed into his mouth and prevented him. In a few moments he died, without speaking the last words which he wished to say.”

The execution squads also killed Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot that day. They thus eliminated the leaders of the Ridge Party.

Following the executions, the Ridge family fled to Fayetteville, Arkansas. John Ridge died without a will, leaving behind a fairly large estate consisting of slaves, stock, and other personal property. Due to the chaotic state of the Cherokee nation, the estate was not immediately settled and thus the Ridge family found themselves often short of funds.

John Rollin Ridge received much of his formal education in Arkansas. In 1843, he enrolled in the Great Barrington Academy in Massachusetts. While enrolled in the Academy, he heard that his uncle Stand Watie had killed James Foreman, the assassin of Major Ridge. He wrote to his uncle:

“You cannot imagine what feelings of pleasure it gave me when I heard of the death of him who was the murderer of my venerable and beloved grandfather.”

In the same letter he also expresses extreme dislike – some would say hatred – for John Ross.

By 1847, John Rollin Ridge had moved back to Cherokee country, had married Elizabeth Wilson (a non-Cherokee), and had purchased a farm. The estate of John Ridge was settled and John Rollin received two slaves and other items. At this time, he began writing poetry under the name of Yellowbird as well as articles on Cherokee history and politics.

In 1849 John Rollin Ridge had an argument with his neighbor over a missing stallion. During the argument, John Rollin killed David Kell, a pro-Ross man. Fearing that he could not receive a fair trial in the Cherokee Nation because of John Ross and his followers, John Rollin Ridge fled to Missouri. Later it was determined that Kell had been encouraged by Ross supporters to provoke a fight with John Rollin in order to have an excuse to kill him.

In 1850, John Rollin Ridge, his brother Aeneas, and a slave named Wacooli joined a large party which was headed for the California gold fields. His intention was to engage in mining and amass a fortune. However, the journey to California proved to be more expensive and more difficult than he had thought. Along the way, he had to abandon a wagon, equipment, and clothing. Eventually he arrived in Placerville to find that thousands of people were already digging for gold. He soon learned that gold mining was hard physical work and that very few gold miners ever struck it rich.

John Rollin Ridge arrived in Sacramento looking for a job-any job that was honest. It was here that he met the local agent for the New Orleans newspaper True Delta and wrote a sample article. The agent quickly realized that it was a well-written article and John Rollin Ridge became a correspondent for True Delta. Thus he began his newspaper career in California.

The writings and poetry of John Rollin Ridge were soon appearing in a number of California publications including Alta California, Golden Era, Hesperian, Marysville Herald, Daily Union, and Hutching’s California Magazine.

In 1854, his book The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit was published. The book was widely read and frequently plagiarized. While John Rollin Ridge claimed that the story was true and was important to the early history of the state, there are some literary critics today who classify the work as a novel.

While working in the newspaper field, his dream was to establish a newspaper that would be devoted to Indian affairs, to defend Indian rights, and to provide Indians with powerful friends. He wrote:

“I want to write the history of the Cherokee nation as it should be written and not as white men will write it and as they will tell the tale, to screen and justify themselves.”

This is a dream which he would never realize.

In 1855, John Rollin Ridge became the main writer for the California American, an organ for the Know Nothing Party. One of the Party’s main tenets was that foreigners were unfit for citizenship and that Catholics should be denied citizenship as they were loyal to a foreign power.

In 1857 the Daily Bee began publishing in Sacramento with John Rollin Ridge as its editor. As editor of the Bee Ridge defended female journalists and writers. He wrote:

“The lady-writers of America are among the very best of our contributors to the literature of today.”

As editor of the Daily Bee John Rollin Ridge published many anti-Mormon articles. He opposed the creation of a Mormon state in Utah. He argued against mixing religion and politics. He wrote:

“A minister of the gospel, therefore, in the United States, who would speak of politics in the pulpit, and seek to array religion and politics together, is nothing better than a vile incendiary, torch in hand, in the very temple of our liberties, and deserves to be looked upon as a common enemy, taken down from the position which he disgraces, and branded with universal contempt.”

While at the Daily Bee, John Rollin Ridge began writing about Indians. While Ridge agreed with the popular opinion that the “digger” Indians were inferior, he disagreed with the popular notion that genocide was the solution. Ridge felt that California’s Indians were inferior to the Indians of the East and to those of South America.

The term “digger” Indians was used at the time to refer to a number of different tribes. The term comes from their practice of digging for roots.

With regard to Indians in North America since the European invasion, Ridge wrote:

“The Indian’s rights have been best respected, since the first white settlement of this continent, in those places where he has held his ground by bow and gun, tomahawk and scalping knife; where he has shown himself a warrior, and ready to mingle his blood with the soil upon which he grew, rather than leave it; where he had met encroachment upon his rights, or what he deemed his rights, by the torch of midnight conflagration and the death-menacing war whoop and the death-dealing tomahawk; where he has made it unsafe to lie down at night or to get up in the morning or to journey forth by day-There has his title to land been recognized and there has he been negotiated with and there have mutual terms of peace been subscribed to and respected.”

In 1857, writing under the name Yellow Bird, John Rollin Ridge provided a sketch of Si Bolla, a leader of one of the “digger” Indian bands. The account expressed admiration for the man’s intelligence and speaking ability. Although Ridge considered the “diggers” to be inferior, he defended them against the Americans who persecuted and enslaved them.

John Rollin Ridge left the Daily Bee to become the editor of the Express in Marysville. He then became the editor of the short-lived Marysville News. He then joined the Daily National Democrat whose banner proudly proclaimed: “The Voice of the People is the Voice of God.”

In 1861, Ridge became the editor of the anti-Lincoln and antiabolitionist Evening Journal in San Francisco. While he felt that Lincoln and the abolitionists would destroy the Union, Ridge declared his support for the Union and declared that the Evening Journal would be independent from any political party.

After a few months with the Evening Journal, Ridge moved to another San Francisco paper, the National Herald. His main assignment at the National Herald was to write on political affairs.

While in San Francisco, John Rollin Ridge wrote three long works on the American Indian for the Hesperian. In the first article, he speculated on the origin of the Indians, noting characteristics that are similar to those of the Greeks, Persians, Jews, and Chaldeans. The second article centered on the religious beliefs of the Indians and their mythology. The third article focused on Indian priests, prophets, and medicine men. In his discussion of the Medawin (the priests), he writes:

“The secret grips and signs [of the Medawin] have been recognized as identical with some of the grips and signs of Free Masonry.”

In 1862, Ridge left San Francisco to take a temporary position with the Beacon in Red Bluff. While at Red Bluff, Ridge wrote a number of articles about the Cherokee in which he criticized Cherokee chief John Ross.

After a few months in Red Bluff, he traveled to Weaverville where he helps establish the Trinity National. Following the demise of the paper after only a few issues, he wrote for a number of other papers.

John Rollin Ridge died on October 5, 1867 and was buried in Grass Valley, California. The cause of death was diagnosed as “brain fever” or encephalitis lethargia. The Alta California wrote:

“as a poet, he deserves a prominent position, and as a general writer he was forcible, elegant and polished, his chief forte being that of politics.”

In 1933, the Native Sons of the Golden West erected a marker on his grave which reads in part:

“John Rollin Ridge-California poet, Author of ‘Mount Shasta’ and Other Poems.”