The Puget Sound War

In 1855, concerned about a potential Indian uprising, American settlers in the Puget Sound area of Washington formed four companies of soldiers. One of these companies, Eaton’s Rangers, attempted to apprehend Nisqually chief Leschi. Leschi and his brother Quiemuth were peacefully cultivating their wheat fields when the Rangers moved in. Warned of the Rangers’ approach, Leschi and Quiemuth fled their homes. This action by the Rangers against peaceful Indians started the Puget Sound War. Following this initial incident, the Rangers then roamed the country harassing peaceful Indians.

Nisqually warriors under the leadership of Leschi attacked the Americans in the White River Valley. They were careful to attack only the American volunteers. They made it known to the American settlers that they were protesting Stevens’ treaties. In the words of one settler:

“The Indians sent us word not to be afraid-that they would not harm us.”

At White River, two American families were warned that the Indians were coming. The families, some of whom were members of the volunteer companies, stayed and were attacked. Nine people were killed, but the warriors took the children-two boys and a girl-and delivered them unharmed to an American steamer at Point Elliot.

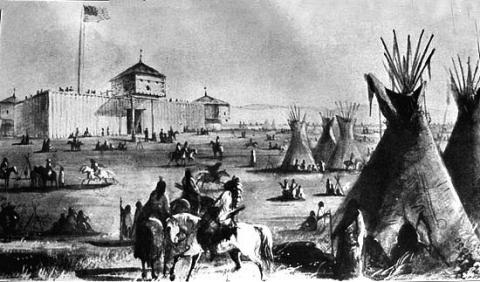

The Americans responded to the White River “massacre” by herding 4,000 peaceful Indians to Fox Island so that they could be carefully watched. Many of the captives died from inadequate food and shelter.

Leschi attempted to draw all of the tribes of Western Washington into a general war against the Americans, but his coalition of Nisqually and Puyallup warriors never numbered more than a few hundred.

The Indian tribes in the southwestern portion of the territory were in close communication with Nisqually, Klickatat, and Yakama warriors. While these tribes had no tradition of warfare, but tended to be business-oriented (i.e. traders), the Americans were fearful that they would join the Indian uprisings. Americans with rifles began to raid the peaceful Indian villages, disarming the Indians, and placing them under surveillance. Some of the Indians-Upper and Lower Chehalis-were herded together on Sidney Ford’s farm near Steilacoom; some of the coastal Indians, including the Cowlitz, were placed in a “local reservation” on the Chehalis River; and the Chinook were placed inland at Fort Vancouver. The Indians were crowded together, denied access to adequate food, and stripped of their personal property. The southwestern tribes were held captive for almost two years during the Puget Sound War.

In 1856, Governor Isaac I. Stevens, responding to the Indian war led by Leschi, called for the extermination of all “hostile” Indians. In response to the Governor’s call for extermination, a small group of about 100 Duwamish, Taitnapam, Puyallup, Nisqually, and Suquamish warriors attacked the community of Seattle. The attack resulted in two American deaths and no Indian deaths. Some described it as a “half-hearted” affair.

Encouraged by Stevens’ call for extermination, American volunteers began to hunt down peaceful Indians. At the Nisqually River, the Washington Mounted Rifles under the command of H.J.G. Maxon murdered a group of 30 Indians who had gathered to fish. Nearly all of the Indians were women and children.

Governor Stevens detained people who were opposed to his war against the Indians. When the Chief Justice of the Territory issued a writ of habeas corpus for the release of these opponents, the Governor simply declared martial law:

“Whereas, in the prosecution of the Indian war, circumstances have existed affording such grave cause of suspicion, such that certain evil disposed persons of Pierce county have given aid and comfort to the enemy, that they have been placed under arrest, and ordered to be tried by a military commission; and whereas, efforts are now being made to withdraw, by civil process, these persons from the purview of the said commission.”

With these words, the Governor suspended the functions of all civil officers in the county.

Wishing to put an end to the bloodshed, Leschi sent his brother Quiemuth as an emissary to the Governor to indicate his willingness to surrender. Quiemuth was murdered in the Governor’s office. While the murderer was arrested, he was not brought to trial as none of the Americans would testify against him.

Stevens renewed his calls for the Indian leaders’ heads and offered a reward. In response, Sluggia, Leschi’s nephew, revealed his uncle’s location in exchange for 50 blankets. Subsequently, Leschi was captured by the Americans.

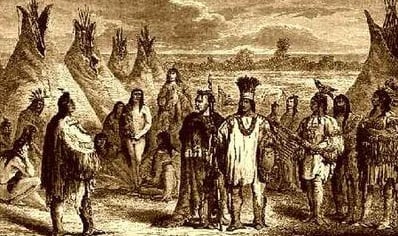

As a result of this brief war in which the Indian warriors demonstrated impressive powers, the Americans met with the Indians at Fox Island. The Indians told the Americans of their dissatisfaction with the 1855 treaties and the Americans promised to give them larger tracts with ground for horses.

For his leadership in the war against Washington colonists, Nisqually chief Leschi was tried in an American court. Despite testimony that Leschi was seen by reliable witnesses at an entirely different location at the time of the specific crimes of which he was accused and couldn’t have committed them, he was found guilty of murder. In 1858 he was hung.

From the American viewpoint, the trial showed their superiority and authority over the Indians and their sense of fairness. Indians, however, were baffled by the American response to murder. Among the Indian nations of Western Washington, homicides were not viewed as crimes that imperiled the public order. Homicides were seen as injuries to and by individuals and their families. The adjudication of homicide, therefore, involved these families and making restitution for the deaths. This was often called “covering the dead” and involved payments from one family to another. Justice was about healing, not punishment.