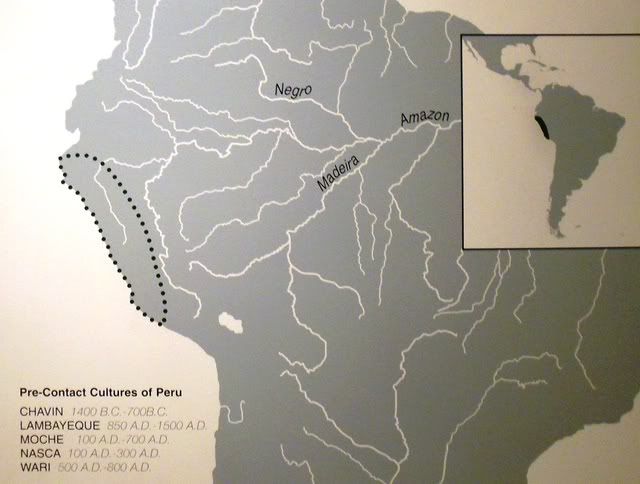

While the Inka are the best-known pre-Columbian civilization in South America, there were other earlier and longer-lasting highly developed civilizations. Tiwanaku (also spelled Tiahuanaco and Tiahuanacu) is generally recognized by archaeologists as an important precursor of the Inka Empire. Tiwanaku, located on the southeastern shore of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia, was a major city-state that controlled parts of the Andean highlands for about five centuries.

Tiwanaku is at an elevation of 3,850 meters (2.4 miles) which makes it one of the highest imperial cities in the world.

About 1500 BCE, Tiwanaku was a small, agricultural village. By about 300 BCE, the village appears to have grown into a religious site which attracted pilgrims from the surrounding area. The religious or cosmological power of Tiwanaku seems to have provided the basis for its later development into a powerful city-state.

Agriculture:

While Tiwanaku is located in an area which has abundant wild resources-fish, birds, wild plants-its rise to power, like that of other city-states, was based on agriculture. The Titicaca Basin has predictable and abundant rainfall. The people of Tiwanaku developed an agricultural system which utilized this rainfall. The people of the Titicaca Basin developed a farming technique which used a flooded-raised field type of agriculture.

The agricultural fields were created by cutting deep canals in the soils next to the lake. Then soils were thrown up to form long, low mounds which improved the drainage of the fields. The canals supply moisture for growing crops, and in addition they also absorb heat from solar radiation during the day. Nights in the Titicaca Basin can be bitterly cold, often producing frost. At night, the heat that had been absorbed in the shallow canals is emitted which provides thermal insulation for the crops.

The canals also had another use: they were used to farm edible fish. Then the resulting canal sludge was dredged up and used for fertilizer.

The fields were used for growing potatoes and quinoa.

This type of agriculture, known as suka kollus, is very labor intensive, but it produces good yields. Traditional agricultural methods in this region can produce 2.4 metric tons of potatoes per hectare, and modern agriculture-which uses artificial fertilizers and pesticides-produces about 14.5 metric tons. On the other hand, the ancient suka kollus agriculture can produce 21 tons per hectare.

Social Stratification:

The productive agricultural system of Tiwanaku contributed to and supported population growth. The population consequently became more complex, with specialized jobs for each member of the society. At the top of the social hierarchy were the elite who lived separated from the commoners by walls which were surrounded by a moat. Some archaeologists have suggested that the moat created the image of a sacred island on which the elite lived. Commoners may have been allowed to enter the elite complex only for ceremonial purposes.

The Empire:

About 300 CE, Tiwanaku was making the transition from a regionally dominant culture force, to an actual empire. It expanded its culture, its way of life, and its religion into other areas of modern-day Peru, Bolivia, and Chile.

Like empires throughout the world, Tiwanku grew through a combination of political, economic, religious, and military power. It used politics to negotiate trade agreements which made other cultures dependent upon them. It reinforced this dependence through religion, as Tiwanaku was always seen as a religious center. Some of the religious statues from these other cultures were taken back to Tiwanaku where they were placed in a subordinate position to the gods of Tiwanaku. In this way, they displayed their religious superiority over these cultures.

The primary Tiwanaku diety, which is shown on reliefs and in statues, is represented as a male figure with a rayed headdress and two staves. This figure seems to have been derived from the Staff God of the earlier Chavin culture.

Control over the empire often involved colonization and migration. Small groups of colonists from Tiwanaku would settle in key resource areas and thus provide Tiwanaku with access to these resources. In addition, people from the outlying areas were resettled closer to the city. The result was a series of multiethnic communities.

Violence may have reinforced the religious and cultural superiority of Tiwanaku. The archaeological evidence suggests that on top of a building known as the Akipana people were disemboweled and torn apart shortly after death. The disarticulated remains appear to have been laid out for all to see. Some archaeologists have suggested that this was a ritual offering to the gods. The person who was sacrificed was not native to the Titicaca Basin.

The hallucinogenic snuff complex also served to help integrate the empire. This complex involved the use of hallucinogenics in religious ceremonies and manifest themselves in the archaeological record in the form of snuff trays, bone tube inhalers, and decorated mortars and pestles which were used for processing the snuff.

A stone snuff tray is shown above.

By about 600 CE, Tiwanaku could be considered an urban center. At this time, the city covered about 6.5 square kilometers and had a population estimated between 15,000 and 30,000 inhabitants. The three primary valleys dominated by Tiwanaku had an estimated population of 285,000 to 1,482,000.

Trade:

One of the important features in holding the wide-spread empire together was the control of the llama herds. These herds were essential for carrying goods between the urban center of the empire and its periphery. Large caravans of llamas travelled the Tiwanaku road system. The animals may have also served as a symbol of the social and economic distance between the commoners and the elites.

The most important luxury trade item was textiles. Throughout the empire, the people wore characteristic Tiwanku textiles which helped unify the empire, at least during ceremonies. The large herds of alpaca provided the weavers at Tiwanaku with an important raw material. The alpaca and the llama herds were one of the major sources of wealth in the empire.

Architecture:

Between 600 and 700 CE, as Tiwanaku grew as a city, there was a significant increase in monumental architecture. The urban center contains a ceremonial core with several huge temples, a pyramid, and a number of palace structures decorated with cut stone lintels. The palace structures are also decorated with large statues which have been carved in a distinctive style.

Tiwanaku monumental architecture is characterized by its use of large stones. Tiwanaku stone architecture used rectangular blocks which were laid out in regular courses. One of the characteristic features is the use of elaborate drainage systems. Drainage systems are sometimes made of red limestone conduits which are held together by bronze architectural cramps.

In some cases I-shaped architectural cramps were made by cold hammering. In other cases, the cramps were created by pouring molten metal into I-shaped sockets which had been carved into the stone.

Some of the stone blocks were decorated with carved images and designs. There are also carved doorways and large stone monoliths.

The feature known as the Gateway to the Sun is shown above.

The stone blocks used at Tiwanaku were quarried some distance from the site. The red sandstone used at the site came from a quarry about 10 kilometers (6 miles) away. The largest of these stones weighs 131 metric tons and transporting them without wheeled vehicles or draft animals was a challenge.

The elaborate carvings and monoliths at Tiwanaku were created from green andesite stone that originated on the Copacabana peninsula, located across the lake from the city. The large andesite stones, some of which weighed over 40 tons, were probably transported across Lake Titicaca by means of reed boats. This is a distance of about 90 kilometers (55 miles). They were then dragged another 10 kilometers to the city itself.

Buildings:

Among the buildings which have been excavated by archaeologists and which are visible to modern visitors are the stepped platforms known as the Akapana, Akapana East, and Pumapunku; the enclosures known as the Kalasasaya and Putuni; and the Semi-Subterranean Temple.

The Akapana is a cross-shaped pyramid which stands nearly 17 meters in height. At its center there appears to have been a sunken court (this has been almost entirely destroyed by looters). There is a staircase with sculptures on the western side. The entire structure is an artificial earthen mound that was faced with a combination of large and small stone blocks. The dirt for the structure appears to have come from the moat which surrounds the site.

The feature designated as Akapana East marks the boundary for the ceremonial center and urban area. It was made from a floor of sand and clay that supported a group of buildings.

The platform mound designated as the Pumapunku was built on an east-west axis like the Akapana. It is a rectangular, terraced earthen mound which was faced with megalithic blocks. While it is only five meters tall, it measures 167 meters by 117 meters. One of the prominent features of the Pumapunka is a stone terrace which was paved with large stone blocks. One of these blocks is estimated to weigh 131 metric tons.

The Kalasasaya is a large courtyard which is outlined by a high gateway. It is located to the north of the Akapana. Near this courtyard is the Semi-Subterrean Temple-a square, sunken courtyard that was constructed on a north-south axis rather than an east-west axis. The walls are covered with tenon heads of many different styles.

Decline:

About 950 CE, there was a climatic change: the amount of precipitation in the Titicaca Basin dropped significantly. As the rain decreased, the political and religious power of Tiwanaku and its elites also declined. As food became more scarce, the power of the elite waned. Fifty years later Tiwanaku was abandoned.

The city of Tiwanaku and its empire left no written history. What we know about Tiwanaku comes from later historical accounts and from archaeology.

Leave a Reply