When the Spanish explorer Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo arrived in what was to become Los Angeles in 1542, his ship anchored off Santa Catalina Island where it was greeted by a large canoe filled with Indian people who called themselves kumi.vit, and who would later be identified as the Gabreleño/Gabrielino-Tongva.

The Gabreleño-Tongva occupied the area as well as the four southern Channel Islands. There were about 50 permanent villages in the area (some sources indicate that there may have been as many as 100 villages), each with 100 to 300 inhabitants. In their chapter on the Gabrielino in the Handbook of North American Indians, Lowell John Bean and Charles Smith report:

“With the possible exception of the Chumash, the Gabrielino were the wealthiest, most populous, and most powerful ethnic nationality in aboriginal southern California, their influence spreading as far east as the Colorado River, and south into Baja California.”

The language spoken by the Tongva is classified as a Cupan language in the Takic language family which is a part of the larger Uto-Aztecan linguistic stock. Evidence suggests that there were at least four major dialects: Gabrielino, spoken in the Los Angeles basin area; Fernandeño, spoken by the people living north of the Los Angeles basin in the San Fernando valley area; Santa Catalina Island dialect; and San Nicolas Island dialect. Lowell John Bean and Charles Smith report:

“There were probably dialectical differences also between many mainland villages, a result not only of geographical separation but also social, cultural, and linguistic mixing with neighboring non-Gabrielino speakers.”

The Mission

In 1771, the Franciscans established the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel on the banks of the Rio Hondo.

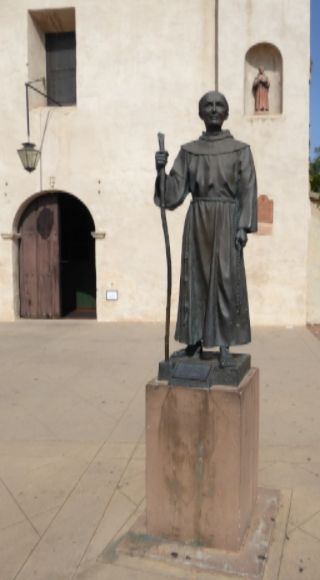

Shown above is the statue of Frey Junipero Serra in front of the San Gabriel Mission. While the Catholic Church considers him a saint, many Indian people view him as a evil devil whose sadistic practices tortured and killed countless Indian men, women, and children.

Shown above is the statue of Frey Junipero Serra in front of the San Gabriel Mission. While the Catholic Church considers him a saint, many Indian people view him as a evil devil whose sadistic practices tortured and killed countless Indian men, women, and children.  Shown above is a model of the mission which is on display in the San Gabriel Mission.

Shown above is a model of the mission which is on display in the San Gabriel Mission.

The mission was established to convert the Tongva people in the San Gabriel Valley. The Indians did not greet them with open arms, but with full war paint and hostile gestures. One of the Spaniards reported:

“Our people finally fought their way to the chosen spot, dangerously pressed by the whole multitude of savages.”

After the establishment of the mission, the Tongva became known as the Gabrielino or Gabreleño after the mission.

While it is not uncommon for some textbooks to give the impression that the California Native Americans passively accepted the missions, Spanish domination, and conversion to Christianity, this was not the case. Robert Jackson and Edward Castillo, in their book Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians, put it this way:

“The initial reception of the Franciscans by the California Indians was anything but hospitable.”

Resistance to the Spanish Franciscans was organized by village chiefs and influential shamans and this resistance was expressed through attacks on both the Spanish soldiers and the Franciscan missionaries. According to Robert Jackson and Edward Castillo:

“The overt hostility of the Indians through much of coastal California during the first years of the Franciscan mission program slowed the rate of the establishment of the new missions and created a reliance on soldiers to protect the Franciscans.”

Within a year, the Indians attacked the San Gabriel Mission. The two attacks were triggered by the rape of a Kumi.vit woman by the soldiers who were assigned to protect the Franciscans. One chief was killed, and the Spanish soldiers placed his head on a pole as an example to other Indians who might wish to rebel against Spanish authority.

Los Angeles County Natural History Museum

The Los Angeles County Natural History Museum has a small display on the Gabreleño-Tongva. According to the Museum display:

“The Gabreleño-Tongva, together with their Chumash neighbors to the north, occupied the Channel Islands, mainland coastal areas, territories further inland in Southern California. Canoe routes carried people, food, raw materials and manufactured goods between the islands and the mainland, as well as from island to island.”

With regard to Native water craft, the Museum display states:

“The Gabreleño-Tongva ti’at (canoe) and Chumash tomol (canoe) were impressive sewn boats that could hold up to twenty people. Canoe builders carved planks from driftwood, then drilled holes so that the planks could be sewn together. As they constructed their boat, the builders put hot tar between rows of planks and into the drill holes so the ti’at or tomol would not sink.”

Shown above is an ancient steatite carving of a canoe from San Nicholas Island.

Shown above is an ancient steatite carving of a canoe from San Nicholas Island.  Shown above is a steatite ladle used for applying the hot tar.

Shown above is a steatite ladle used for applying the hot tar.

Steatite was a major trade item which was available in great quantities on Santa Catalina Island. Lowell John Bean and Charles Smith report:

“Most of the steatite was used to make palettes, arrow straighteners, ornaments, and carvings of animal or animal-like beings.”

According to the Museum display:

“The Channel Islands contained resources that the The Gabreleño-Tongva and Chumash residents used to produce desirable objects. Skilled craftspeople built workshops near sources of raw material and produced manufactured objects that were traded to the mainland.”

Shown above are a mortar and pestle from San Miguel Island.

Shown above are a mortar and pestle from San Miguel Island.

According to the Museum display:

“Food security for the The Gabreleño-Tongva depended on the practice of harvesting seasonal abundance, then preserving and storing extra food for years when wild crops failed. An elaborate system of formal ceremonial trade between neighboring villages allowed for the exchange of food, shell money beads and other valuable objects. This evened out resources and further ensured food security for villages experiencing lean years.”

Shown above is a willow acorn storage granary.

Shown above is a willow acorn storage granary.

According to the Museum display:

“Granaries like this one provided excellent storage for acorns and mesquite beans. The basket’s loosely woven construction allowed airflow to prevent mildew. Granaries were raised off the ground to keep the harvest away from pests. Large baskets like this one could keep properly dried acorns good for three years and were used through the 1800s.”

Shown above are strings of beads which were used as a form of money.

Shown above are strings of beads which were used as a form of money.  Shown above is a ground stone axe head.

Shown above is a ground stone axe head.

Leave a Reply